Archive for September, 2020

» posted on Saturday, September 19th, 2020 by Linda Lou Burton

A Talking-To

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – Summer is nearing an end, and I’m wagging my finger to get your attention this Saturday evening about COVID19 in the United States and the World. The virus hasn’t disappeared yet, and sadly, the United States continues to be coping poorly. The World Health Organization reports 30,369,778 cases tallied up around the globe as of September 19. The Centers for Disease Control reports 6,706,374 cases in the United States as of September 19. Do the math: 22% of the COVID19 cases in the world are in the United States. And remember, the United States accounts for only 4% of the world’s population.

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – Summer is nearing an end, and I’m wagging my finger to get your attention this Saturday evening about COVID19 in the United States and the World. The virus hasn’t disappeared yet, and sadly, the United States continues to be coping poorly. The World Health Organization reports 30,369,778 cases tallied up around the globe as of September 19. The Centers for Disease Control reports 6,706,374 cases in the United States as of September 19. Do the math: 22% of the COVID19 cases in the world are in the United States. And remember, the United States accounts for only 4% of the world’s population.

I REPEAT:

- WORLD COVID19 cases: 30,369,778

- UNITED STATES COVID19 cases: 6,706,374

- UNITED STATES: 22% of World COVID19 cases

- UNITED STATES: 4% of World population

As to DEATHS from COVID19, the World Health Organization reports 948,795 deaths worldwide due to COVID19 as of September 19. The Centers for Disease Control reports 198,099 deaths in the United States due to COVID19 as of September 19.

My stepmother was one of those statistics. She was buried September 13 in Jasper, Alabama (Alabama now the fifth deadliest state to live in). Her name was Opal Burton and she lived for 97 years, until she contracted the virus while quarantined in a nursing home. Not the way anyone should spend their last days on earth; she was in a place that should have been able to keep her safe. It makes me sad, and it makes me angry that we have let this virus dig into our lives the way it has. God bless you Opal, and forgive the laxity that allowed things to get so far beyond control. Your life was much too valuable to be lost in such a way.

DEATHS:

- WORLD COVID19 deaths: 948,795

- UNITED STATES COVID19 deaths: 198,099

- UNITED STATES: 21% of World COVID19 deaths

- UNITED STATES: 4% of World Population

Within the United States, which states have the WORST RECORD?

The FIVE STATES with the HIGHEST percentage of their population DIAGNOSED with COVID19:

- Louisiana: 3.47%. Governor John Bell Edwards, Democrat

- Mississippi: 3.13%. Governor Tate Reeves, Republican

- Florida: 3.12%. Governor Ron DeSantis, Republican

- Arizona: 2.93%. Governor Doug Ducey, Republican

- Alabama: 2.91%. Governor Kay Ivey, Republican

Of those who contracted COVID19, the FIVE STATES with the HIGHEST percentage of those DYING from the virus:

- Connecticut: 8.09%. Governor Ned Lamont, Democrat

- New Jersey: 8.08%. Governor Phil Murphy, Democrat

- New York: 7.29%. Governor Andrew Cuomo, Democrat

- Massachusetts: 6.89%. Governor Charles Baker, Republican

- New Hampshire: 5.57%. Governor Chris Sununu, Republican

We’ve got to do better people. What are YOU doing personally to make sure the virus doesn’t grab onto your beautiful body? And if it unfortunately HAS DONE THAT, and you are feverish and coughing and feel totally pukey BAD, what are you doing to make sure you don’t spread it around? Our powers in office can make good or bad decisions about issuing mandates and opening or closing facilities. But it is up to YOU to practice good common sense. You’ve heard enough details about COVID19 symptoms, and dangers. You know the drill. In all the political froo-froo and blame-game playacting, it’s still WE THE PEOPLE who can slow the virus down by sensible behavior and good judgment. Don’t be a ding-dong!

We’ve got to do better people. What are YOU doing personally to make sure the virus doesn’t grab onto your beautiful body? And if it unfortunately HAS DONE THAT, and you are feverish and coughing and feel totally pukey BAD, what are you doing to make sure you don’t spread it around? Our powers in office can make good or bad decisions about issuing mandates and opening or closing facilities. But it is up to YOU to practice good common sense. You’ve heard enough details about COVID19 symptoms, and dangers. You know the drill. In all the political froo-froo and blame-game playacting, it’s still WE THE PEOPLE who can slow the virus down by sensible behavior and good judgment. Don’t be a ding-dong!

In 45 days, it’s time to VOTE. Stay tuned for a daily post about each of the 45 presidents who have already served, from GEORGE to DONALD. You DO NOT want to miss that. If you think things are crazy NOW, well, they are, but there has been mucho craziness in the past too.

Don’t despair. You know what to do on November 3.

» posted on Monday, September 7th, 2020 by Linda Lou Burton

Know Your Neighbors 2 – South America

September 7, 2020, Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – A little more  detail on the twelve countries of South America. Which country has the largest military budget? Which country has the lowest per capita GDP? Which countries have emeralds and diamonds? Which country has Dutch as their official language? In which country is life expectancy for females the highest? In which country is life expectancy for males the lowest? In which country do the most people claim to be Catholic? How well do you know your neighbors?

detail on the twelve countries of South America. Which country has the largest military budget? Which country has the lowest per capita GDP? Which countries have emeralds and diamonds? Which country has Dutch as their official language? In which country is life expectancy for females the highest? In which country is life expectancy for males the lowest? In which country do the most people claim to be Catholic? How well do you know your neighbors?

Countries in South America

- Argentina

- Bolivia

- Brazil

- Chile

- Colombia

- Ecuador

- Guyana

- Paraguay

- Peru

- Suriname

- Uruguay

- Venezuela

Argentina, Capital City Buenos Aires

Argentina, the third largest South American country by population (45,089,492), is a presidential republic with a president as head of state and head of government. The official language is Spanish and the country is 77% Catholic and 11% Protestant and 7% Agnostic. The defense budget is $4.2 billion and there are 74,200 active troops. Natural resources are lead, copper, iron ore, petroleum. The Per Capita GDP is $20,567. Compulsory education ages 4-17. Life expectancy female 81.0; male 74.5.

Argentina, the third largest South American country by population (45,089,492), is a presidential republic with a president as head of state and head of government. The official language is Spanish and the country is 77% Catholic and 11% Protestant and 7% Agnostic. The defense budget is $4.2 billion and there are 74,200 active troops. Natural resources are lead, copper, iron ore, petroleum. The Per Capita GDP is $20,567. Compulsory education ages 4-17. Life expectancy female 81.0; male 74.5.

Bolivia, Capital City La Paz

Bolivia, the eighth largest South American country by population (11,473,676), is a presidential republic with a president as head of state and head of government. The primary language is Spanish and the country is 79% Catholic and 9% Protestant. The defense budget is $533 million and there are 34,100 active troops. Natural resources are natural gas, iron ore, petroleum, timber. The Per Capita GDP is $7,859. Compulsory education ages 4-17. Life expectancy female 73.1; male 67.3.

Bolivia, the eighth largest South American country by population (11,473,676), is a presidential republic with a president as head of state and head of government. The primary language is Spanish and the country is 79% Catholic and 9% Protestant. The defense budget is $533 million and there are 34,100 active troops. Natural resources are natural gas, iron ore, petroleum, timber. The Per Capita GDP is $7,859. Compulsory education ages 4-17. Life expectancy female 73.1; male 67.3.

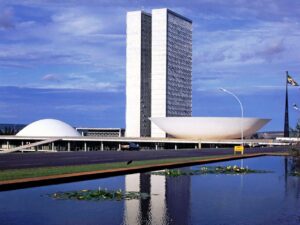

Brazil, Capital City Brasilia

Brazil, the largest South American country by population (210,301,591), is a federal presidential republic with a president as head of state and head of government. The official language is Portuguese and the country is 65% Catholic, 14% Protestant, and 11% Independent. The defense budget is $28 billion and there are 334,500 active troops. Natural resources are gold, iron ore, petroleum, timber. The Per Capita GDP is $16,068. Compulsory education ages 4-17. Life expectancy female 78.2; male 71.0.

Brazil, the largest South American country by population (210,301,591), is a federal presidential republic with a president as head of state and head of government. The official language is Portuguese and the country is 65% Catholic, 14% Protestant, and 11% Independent. The defense budget is $28 billion and there are 334,500 active troops. Natural resources are gold, iron ore, petroleum, timber. The Per Capita GDP is $16,068. Compulsory education ages 4-17. Life expectancy female 78.2; male 71.0.

Chile, Capital City Santiago

Chile, the sixth largest South American country by population (18,057,855), is a presidential republic with a president as head of state and head of government. The official language is Spanish and the country is 61% Catholic, 22% Independent, and 9% Agnostic. The defense budget is $4.2 billion and there are 77,200 active troops. Natural resources are copper, timber, nitrates, hydropower. The Per Capita GDP is $25,284. Compulsory education ages 5-17. Life expectancy female 82.4; male 76.2.

Chile, the sixth largest South American country by population (18,057,855), is a presidential republic with a president as head of state and head of government. The official language is Spanish and the country is 61% Catholic, 22% Independent, and 9% Agnostic. The defense budget is $4.2 billion and there are 77,200 active troops. Natural resources are copper, timber, nitrates, hydropower. The Per Capita GDP is $25,284. Compulsory education ages 5-17. Life expectancy female 82.4; male 76.2.

Colombia, Capital City Bogota

Colombia, the second largest South American country by population (48,631,464), is a presidential republic with a president as head of state and head of government. The official language is Spanish and the country is 86% Catholic, 9% Protestant, and 3% Agnostic. The defense budget is $10.6 billion and there are 292,200 active troops. Natural resources are copper, emeralds, hydropower. The Per Capita GDP is $14,999. Compulsory education ages 5-14. Life expectancy female 79.7; male 73.3.

Colombia, the second largest South American country by population (48,631,464), is a presidential republic with a president as head of state and head of government. The official language is Spanish and the country is 86% Catholic, 9% Protestant, and 3% Agnostic. The defense budget is $10.6 billion and there are 292,200 active troops. Natural resources are copper, emeralds, hydropower. The Per Capita GDP is $14,999. Compulsory education ages 5-14. Life expectancy female 79.7; male 73.3.

Ecuador, Capital City Quito

Ecuador, the seventh largest South American country by population (16,703,254), is a presidential republic with a president as head of state and head of government. The official language is Spanish and the country is 84% Catholic, 11% Protestant, and 4% Agnostic. The defense budget is $1.7 billion and there are 40,250 active troops. Natural resources are petroleum, fish, timber, hydropower. The Per Capita GDP is $11,714. Compulsory education ages 3-17. Life expectancy female 80.5; male 74.4.

Ecuador, the seventh largest South American country by population (16,703,254), is a presidential republic with a president as head of state and head of government. The official language is Spanish and the country is 84% Catholic, 11% Protestant, and 4% Agnostic. The defense budget is $1.7 billion and there are 40,250 active troops. Natural resources are petroleum, fish, timber, hydropower. The Per Capita GDP is $11,714. Compulsory education ages 3-17. Life expectancy female 80.5; male 74.4.

Guyana, Capital City Georgetown

Guyana, the eleventh largest South American country by population (744,845), is a parliamentary republic with a president as head of state and head of government. The official language is English and the country is 34% Protestant, 30% Hindu, 11% Independent, and 8% Muslim. The defense budget is $56 million and there are 3,400 active troops. Natural resources are bauxite, diamonds, timber, shrimp. The Per Capita GDP is $8,569. Compulsory education ages 6-11. Life expectancy female 72.4; male 66.2.

Guyana, the eleventh largest South American country by population (744,845), is a parliamentary republic with a president as head of state and head of government. The official language is English and the country is 34% Protestant, 30% Hindu, 11% Independent, and 8% Muslim. The defense budget is $56 million and there are 3,400 active troops. Natural resources are bauxite, diamonds, timber, shrimp. The Per Capita GDP is $8,569. Compulsory education ages 6-11. Life expectancy female 72.4; male 66.2.

Paraguay, Capital City Asuncion

Paraguay, the ninth largest South American country by population (7,108,524), is a presidential republic with a president as head of state and head of government. The official languages are Spanish and Guarani and the country is 85% Catholic, 11% Protestant. The defense budget is $313 million and there are 11,500 active troops. Natural resources are hydropower, timber, limestone. The Per Capita GDP is $13,571. Compulsory education ages 5-17. Life expectancy female 80.5; male 75.0.

Paraguay, the ninth largest South American country by population (7,108,524), is a presidential republic with a president as head of state and head of government. The official languages are Spanish and Guarani and the country is 85% Catholic, 11% Protestant. The defense budget is $313 million and there are 11,500 active troops. Natural resources are hydropower, timber, limestone. The Per Capita GDP is $13,571. Compulsory education ages 5-17. Life expectancy female 80.5; male 75.0.

Peru, Capital City Lima

Peru, the fifth largest South American country by population (31,624,207), is a presidential republic with a president as head of state and head of government. The official languages are Spanish, Quechua and Aymara and the country is 84% Catholic, 12% Protestant. The defense budget is $2.3 billion and there are 81,000 active troops. Natural resources are copper, petroleum, fish, coal. The Per Capita GDP is $14,393. Compulsory education ages 3-16. Life expectancy female 76.7; male 72.3.

Peru, the fifth largest South American country by population (31,624,207), is a presidential republic with a president as head of state and head of government. The official languages are Spanish, Quechua and Aymara and the country is 84% Catholic, 12% Protestant. The defense budget is $2.3 billion and there are 81,000 active troops. Natural resources are copper, petroleum, fish, coal. The Per Capita GDP is $14,393. Compulsory education ages 3-16. Life expectancy female 76.7; male 72.3.

Suriname, Capital City Paramaribo

Suriname, the smallest South American country by population (603,823), is a presidential republic with a president as head of state and head of government. The official language is Dutch though English is widely spoken, and the country is 30% Catholic, 20% Hindu, 16% Muslim, 15% Protestant, 5% Agnostic . The defense budget is NA and there are 1,840 active troops. Natural resources are timber, hydropower, fish, gold. The Per Capita GDP is $15,498. Compulsory education ages 7-12. Life expectancy female 75.6; male 70.6.

Suriname, the smallest South American country by population (603,823), is a presidential republic with a president as head of state and head of government. The official language is Dutch though English is widely spoken, and the country is 30% Catholic, 20% Hindu, 16% Muslim, 15% Protestant, 5% Agnostic . The defense budget is NA and there are 1,840 active troops. Natural resources are timber, hydropower, fish, gold. The Per Capita GDP is $15,498. Compulsory education ages 7-12. Life expectancy female 75.6; male 70.6.

Uruguay, Capital City Montevideo

Uruguay, the tenth largest South American country by population (3,378,471), is a presidential republic with a president as head of state and head of government. The official language is Spanish and the country is 52% Catholic, 30% Agnostic, 9% Protestant, 7% Atheist. The defense budget is $486 million and there are 21,000 active troops. Natural resources are hydropower, fish, minor minerals. The Per Capita GDP is $23,531. Compulsory education ages 4-17. Life expectancy female 81.0; male 74.6.

Uruguay, the tenth largest South American country by population (3,378,471), is a presidential republic with a president as head of state and head of government. The official language is Spanish and the country is 52% Catholic, 30% Agnostic, 9% Protestant, 7% Atheist. The defense budget is $486 million and there are 21,000 active troops. Natural resources are hydropower, fish, minor minerals. The Per Capita GDP is $23,531. Compulsory education ages 4-17. Life expectancy female 81.0; male 74.6.

Venezuela, Capital City Caracas

Venezuela, the fourth largest South American country by population (32,068,672), is a federal presidential republic with a president as head of state and head of government. The official language is Spanish and the country is 81% Catholic, 11% Protestant, 5% Agnostic. The defense budget is $741 million and there are 123,000 active troops. Natural resources are petroleum, gold, hydropower, diamonds. The Per Capita GDP is $18,102. Compulsory education ages 3-18. Life expectancy female 79.5; male 73.4.

Venezuela, the fourth largest South American country by population (32,068,672), is a federal presidential republic with a president as head of state and head of government. The official language is Spanish and the country is 81% Catholic, 11% Protestant, 5% Agnostic. The defense budget is $741 million and there are 123,000 active troops. Natural resources are petroleum, gold, hydropower, diamonds. The Per Capita GDP is $18,102. Compulsory education ages 3-18. Life expectancy female 79.5; male 73.4.

Resource: The World Almanac and Book of Facts 2020

» posted on Sunday, September 6th, 2020 by Linda Lou Burton

Know Your Neighbors – South America

September 6, 2020, Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – Do you know your geography? There are twelve countries in South America – I keep up with them by memorizing them alphabetically.

- Argentina

- Bolivia

- Brazil

- Chile

- Colombia

- Ecuador

- Guyana

- Paraguay

- Peru

- Suriname

- Uruguay

- Venezuela

Where do the most people live?

- Brazil – 210,301,591

- Colombia – 48,631,464

- Argentina – 45,089,492

- Venezuela – 32,068,672

- Peru – 31,624,207

- Chile – 18,057,855

- Ecuador – 16,703,254

- Bolivia – 11,473,676

- Paraguay – 7,108,524

- Uruguay – 3,378,471

- Guyana – 744,845

- Suriname – 603,823

If you had to walk across it, which county would take the longest? Which is largest in square miles?

- Brazil – 3,287,957

- Argentina – 1,073,518

- Peru – 496,225

- Colombia – 439,736

- Bolivia – 424,164

- Venezuela – 352,144

- Chile – 291,933

- Paraguay – 153,399

- Ecuador – 109,484

- Guyana – 83,000

- Uruguay – 68,037

- Suriname – 63,251

Which country has the highest percentage of internet users? Most technologically inclined?

- Chile – 82.3%

- Argentina – 74.3%

- Venezuela – 72.0%

- Uruguay – 68.3%

- Brazil – 67.5

- Paraguay – 65.0%

- Colombia – 62.3%

- Ecuador – 57.3%

- Peru – 52.5%

- Suriname – 48.9%

- Bolivia – 43.8%

- Guyana – 37.3%

Which country has the highest literacy rate? Percent of population able to read and write?

- Argentina – 99.1%

- Uruguay – 98.6%

- Venezuela – 97.1%

- Chile – 96.9%

- Suriname – 95.6%

- Colombia – 94.7%

- Paraguay – 94.7%

- Ecuador – 94.4%

- Peru – 94.1%

- Brazil – 92.6%

- Bolivia – 92.5%

- Guyana – 88.5%

Which country has the highest population density? How many people are there per square mile? Close to each other or lots of breathing space?

- Ecuador – 156

- Colombia – 121

- Venezuela – 94

- Brazil – 65

- Peru – 64

- Chile – 63

- Uruguay – 50

- Paraguay – 46

- Argentina – 43

- Bolivia- 27

- Guyana – 10

- Suriname – 10

Which country has had the most confirmed DEATHS from COVID19 in 2020 to date?

- Brazil – 126,960

- Peru – 29,976

- Colombia – 21,615

- Chile – 11,682

- Argentina – 10,179

- Bolivia – NA

- Ecuador – NA

- Guyana – NA

- Paraguay – NA

- Suriname – NA

- Uruguay – NA

- Venezuela – NA

Which country has had the most confirmed CASES of COVID19 reported in 2020 to date?

- Brazil – 4,147,794

- Peru – 691,575

- Colombia – 671,848

- Argentina – 488,007

- Chile – 425,541

- Bolivia – NA

- Ecuador – NA

- Guyana – NA

- Paraguay – NA

- Suriname – NA

- Uruguay – NA

- Venezuela – NA

Resources: World Almanac and Book of Facts 2020 and World Health Organization

» posted on Saturday, September 5th, 2020 by Linda Lou Burton

Know Your Neighbors 2 – North America

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – A little more detail on the ten countries of North America. Which country has the largest military budget? Which country has the lowest per capita GDP? Which country has mahogany forests? Which countries do not have an official language? In which country is life expectancy for females the highest? In which country is life expectancy for males the lowest? In which country do the most people claim to be Catholic? In how many countries is Queen Elizabeth II Head of State? How well do you know your neighbors?

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – A little more detail on the ten countries of North America. Which country has the largest military budget? Which country has the lowest per capita GDP? Which country has mahogany forests? Which countries do not have an official language? In which country is life expectancy for females the highest? In which country is life expectancy for males the lowest? In which country do the most people claim to be Catholic? In how many countries is Queen Elizabeth II Head of State? How well do you know your neighbors?

Alphabetical List of Countries in North America

- Belize

- Canada

- Costa Rica

- El Salvador

- Guatemala

- Honduras

- Mexico

- Nicaragua

- Panama

- United States

Belize, Capital City Belmopan

Belize, the smallest North American country by population (392,771), is a parliamentary democracy under a constitutional monarchy with Queen Elizabeth II as Head of State. There is a Governor-General representing the Queen, and Prime Minister as Head of Government. The official language is English and the country is 61% Catholic and 27% Protestant. The defense budget is $23 million and there are 1,500 active troops. Natural resources are timber, fish, and hydropower. The Per Capita GPD is $8,786. Compulsory education ages 5-12. Life expectancy female 76.7; male 73.4.

Belize, the smallest North American country by population (392,771), is a parliamentary democracy under a constitutional monarchy with Queen Elizabeth II as Head of State. There is a Governor-General representing the Queen, and Prime Minister as Head of Government. The official language is English and the country is 61% Catholic and 27% Protestant. The defense budget is $23 million and there are 1,500 active troops. Natural resources are timber, fish, and hydropower. The Per Capita GPD is $8,786. Compulsory education ages 5-12. Life expectancy female 76.7; male 73.4.

Canada, Capital City Ottawa

Canada, the third largest North American country by population (36,136,376), is a federal parliamentary democracy under a constitutional monarchy with Queen Elizabeth II as Head of State. There is a Governor-General representing the Queen, and Prime Minister as Head of government. The official languages are English and French and the country is 44% Catholic, 23% Agnostic, 11% Protestant, 4% Muslim. The defense budget is $18.2 billion and there are 66,600 active troops. Natural resources are iron ore and various minerals, fish, timber, coal, petroleum. The per capita GDP is $47,871. Compulsory education ages 6-15. Life expectancy female 84.9, male 79.5.

Canada, the third largest North American country by population (36,136,376), is a federal parliamentary democracy under a constitutional monarchy with Queen Elizabeth II as Head of State. There is a Governor-General representing the Queen, and Prime Minister as Head of government. The official languages are English and French and the country is 44% Catholic, 23% Agnostic, 11% Protestant, 4% Muslim. The defense budget is $18.2 billion and there are 66,600 active troops. Natural resources are iron ore and various minerals, fish, timber, coal, petroleum. The per capita GDP is $47,871. Compulsory education ages 6-15. Life expectancy female 84.9, male 79.5.

Costa Rica, Capital City San Jose

Costa Rica, the eighth largest North American country by population (5,043,084), is a presidential republic with a president as both head of state and head of government. The official language is Spanish and the country is 76% Catholic, 19% Protestant, and 4% Agnostic. The defense budget is $454 million and there are no active troops, rather 9,800 para-military style police. Natural resources are hydropower. The per capita GDP is $17,645. Compulsory education ages 4-16. Life expectancy female 81.9, male 76.3.

Costa Rica, the eighth largest North American country by population (5,043,084), is a presidential republic with a president as both head of state and head of government. The official language is Spanish and the country is 76% Catholic, 19% Protestant, and 4% Agnostic. The defense budget is $454 million and there are no active troops, rather 9,800 para-military style police. Natural resources are hydropower. The per capita GDP is $17,645. Compulsory education ages 4-16. Life expectancy female 81.9, male 76.3.

El Salvador, Capital City San Salvador

El Salvador, the sixth largest North American country by population (6,202,330), is a presidential republic, with a president as both head of state and head of government. The official language is Spanish and the country is 66% Catholic, 15% Independent, and 15% Protestant. The defense budget is $141 million and there are 24,500 active troops. Natural resources are hydropower, geothermal power, and petroleum. The per capita GDP is $8,317. Compulsory education ages 1-15. Life expectancy female 78.8, male 72.1.

El Salvador, the sixth largest North American country by population (6,202,330), is a presidential republic, with a president as both head of state and head of government. The official language is Spanish and the country is 66% Catholic, 15% Independent, and 15% Protestant. The defense budget is $141 million and there are 24,500 active troops. Natural resources are hydropower, geothermal power, and petroleum. The per capita GDP is $8,317. Compulsory education ages 1-15. Life expectancy female 78.8, male 72.1.

Guatemala, Capital City Guatemala City

Guatemala, the fourth largest North American country by population (16,867,133), is a presidential republic with a president as both head of state and head of government. The official language is Spanish and the country is 67% Catholic, 19% Protestant, and 11% Independent. The defense budget is $256 million and there are 18,050 active troops. Natural resources are petroleum, rare woods, fish, and hydropower. The per capital GDP is $8,447. Compulsory education ages 6-15. Life expectancy female 74.2, male 70.1.

Guatemala, the fourth largest North American country by population (16,867,133), is a presidential republic with a president as both head of state and head of government. The official language is Spanish and the country is 67% Catholic, 19% Protestant, and 11% Independent. The defense budget is $256 million and there are 18,050 active troops. Natural resources are petroleum, rare woods, fish, and hydropower. The per capital GDP is $8,447. Compulsory education ages 6-15. Life expectancy female 74.2, male 70.1.

Honduras, Capital City Tegucigalpa

Honduras, the fifth largest North American country by population (9,325,005), is a presidential republic with a president as both head of state and head of government. The official language is Spanish and the country is 72% Catholic and 18% Protestant. The defense budget is $329 million and there are 14,950 active troops. Natural resources are timber, gold, coal, fish, hydropower. The per capita GDP is $5,130. Compulsory education ages 5-16. Life expectancy female 73.1, male 69.7.

Honduras, the fifth largest North American country by population (9,325,005), is a presidential republic with a president as both head of state and head of government. The official language is Spanish and the country is 72% Catholic and 18% Protestant. The defense budget is $329 million and there are 14,950 active troops. Natural resources are timber, gold, coal, fish, hydropower. The per capita GDP is $5,130. Compulsory education ages 5-16. Life expectancy female 73.1, male 69.7.

Mexico, Capital City Mexico City

Mexico, the second largest North American country by population (127,318,112), is a federal presidential republic with a president as both head of state and head of government. The primary language is Spanish and the country is 86% Catholic, 10% Protestant, 3% Agnostic. The defense budget is $5.2 billion and there are 277,150 active troops. Natural resources are petroleum, various minerals, natural gas, timber. The per capita GDP is $19,969. Compulsory education ages 4-17. Life expectancy female 79.4, male 73.7.

Mexico, the second largest North American country by population (127,318,112), is a federal presidential republic with a president as both head of state and head of government. The primary language is Spanish and the country is 86% Catholic, 10% Protestant, 3% Agnostic. The defense budget is $5.2 billion and there are 277,150 active troops. Natural resources are petroleum, various minerals, natural gas, timber. The per capita GDP is $19,969. Compulsory education ages 4-17. Life expectancy female 79.4, male 73.7.

Nicaragua, Capital City Managua

Nicaragua, the seventh largest North American country by population (6,144,442), is a presidential republic with a president as both head of state and head of government. The official language is Spanish and the country is 70% Catholic, 19% Protestant. The defense budget is $82 million and there are 12,000 active troops. Natural resources are gold, copper, lead, timber, fish. The per capita GDP is $5,524. Compulsory education ages 5-11. Life expectancy female 76.4, male 71.7.

Nicaragua, the seventh largest North American country by population (6,144,442), is a presidential republic with a president as both head of state and head of government. The official language is Spanish and the country is 70% Catholic, 19% Protestant. The defense budget is $82 million and there are 12,000 active troops. Natural resources are gold, copper, lead, timber, fish. The per capita GDP is $5,524. Compulsory education ages 5-11. Life expectancy female 76.4, male 71.7.

Panama, Capital City Panama City

Panama, the ninth largest North American country by population (3,847,647), is a presidential republic with a president as both head of state and head of government. The official language is Spanish and the country is 74% Catholic, 10% Protestant, 4% Agnostic. The defense budget is $738 million and there are no armed forces but 26,000 paramilitary police. Natural resources are copper, mahogany, and shrimp. The per capita GDP is $25,509. Compulsory education ages 4-14. Life expectancy female 82.0, male 76.3.

Panama, the ninth largest North American country by population (3,847,647), is a presidential republic with a president as both head of state and head of government. The official language is Spanish and the country is 74% Catholic, 10% Protestant, 4% Agnostic. The defense budget is $738 million and there are no armed forces but 26,000 paramilitary police. Natural resources are copper, mahogany, and shrimp. The per capita GDP is $25,509. Compulsory education ages 4-14. Life expectancy female 82.0, male 76.3.

United States, Capital City Washington, DC

United States, the largest North American country by population (331,883,986), is a constitutional federal republic with a president as both head of state and head of government. The primary languages are English and Spanish and the country is 27% Catholic, 24% Independent, 20% Protestant, 17% Agnostic. The defense budget is $643.3 billion and there are 1,359,450 active troops. Natural resources are coal, various minerals, petroleum, timber. The per capita GDP is $62,641. Compulsory education ages 6-17. Life expectancy female 82.4, male 78.0.

United States, the largest North American country by population (331,883,986), is a constitutional federal republic with a president as both head of state and head of government. The primary languages are English and Spanish and the country is 27% Catholic, 24% Independent, 20% Protestant, 17% Agnostic. The defense budget is $643.3 billion and there are 1,359,450 active troops. Natural resources are coal, various minerals, petroleum, timber. The per capita GDP is $62,641. Compulsory education ages 6-17. Life expectancy female 82.4, male 78.0.

Resource: The World Almanac and Book of Facts 2020

» posted on Friday, September 4th, 2020 by Linda Lou Burton

Know Your Neighbors – North America

September 4, 2020, Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – Do you know your geography? There are ten countries in North America – I keep up with them by memorizing them alphabetically.

- Belize

- Canada

- Costa Rica

- El Salvador

- Guatemala

- Honduras

- Mexico

- Nicaragua

- Panama

- United States

Where do the most people live?

- United States 331,883,986

- Mexico 127,318,112

- Canada 36,136,376

- Guatemala 16,867,133

- Honduras 9,325,005

- El Salvador 6,202,330

- Nicaragua 6,144,442

- Costa Rica 5,043,084

- Panama 3,847,647

- Belize 392,771

If you had to walk across it, which county would take the longest? Which is largest in square miles?

- Canada 3,855,103

- United States 3,796,742

- Mexico 758,449

- Nicaragua 50,336

- Honduras 43,278

- Guatemala 42,042

- Panama 29,120

- Costa Rica 19,730

- Belize 8,867

- El Salvador 8,124

Which country has the highest percentage of internet users? Most technologically inclined?

- Canada 91.0%

- United States 87.3%

- Costa Rica 74.1%

- Mexico 65.8%

- Guatemala 65.0%

- Panama 57.9%

- Belize 47.1%

- El Salvador 33.8%

- Honduras 31.7%

- Nicaragua 27.9%

Which country has the highest literacy rate? Percent of population able to read and write?

- Canada 99.0%

- United States 99.0%

- Costa Rica 97.8%

- Panama 95.0%

- Mexico 94.9%

- Honduras 89.0%

- El Salvador 88.5%

- Nicaragua 82.8%

- Guatemala 81.5%

- Belize 79.1%

Which country has the highest population density? How many people are there per square mile? Close to each other or lots of breathing space?

- El Salvador 763

- Guatemala 401

- Costa Rica 256

- Honduras 215

- Mexico 168

- Panama 132

- Nicaragua 122

- United States 87

- Belize 44

- Canada 9

Which country has had the most confirmed DEATHS from COVID19 in 2020 to date?

- United States 185,687

- Mexico 66,329

- Canada 9,141

- Guatemala 2,825

- Panama 2,046

- Honduras 1,954

- El Salvador 744

- Costa Rica 460

- Nicaragua 141

- Belize 13

Which country has had the most confirmed CASES of COVID19 reported in 2020 to date?

- United States 6,095,007

- Mexico 616,894

- Canada 130,493

- Panama 94,914

- Guatemala 77,040

- Honduras 63,158

- Costa Rica 44,458

- El Salvador 26,099

- Nicaragua 3,773

- Belize 1,118

Which county has the highest percent of their population diagnosed with COVID19 in 2020 to date?

- Panama 2.47%

- United States 1.84%

- Costa Rica 0.88%

- Honduras 0.68%

- Mexico 0.48%

- Guatemala 0.46%

- El Salvador 0.42%

- Canada 0.36%

- Belize 0.28%

- Nicaragua 0.06%

» posted on Thursday, September 3rd, 2020 by Linda Lou Burton

The Lone Ranger

September 3, 2020, Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – The Lone Ranger’s mask, according to movie hype, was designed to protect his identity. I went to many Lone Ranger movies in the early 50s, and even as a popcorn-munching 10-year-old, I knew I’d recognize my idol whether he was masked or not, even if he showed up without his trusty white steed. It did make him rather mysterious and handsome, but that was all. If he believed that little mask did what it was “supposed” to do, he was deluded.

September 3, 2020, Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – The Lone Ranger’s mask, according to movie hype, was designed to protect his identity. I went to many Lone Ranger movies in the early 50s, and even as a popcorn-munching 10-year-old, I knew I’d recognize my idol whether he was masked or not, even if he showed up without his trusty white steed. It did make him rather mysterious and handsome, but that was all. If he believed that little mask did what it was “supposed” to do, he was deluded.

I’m afraid some of us are equally deluded with regard to COVID-19 masks. Count me in that corner. I have been of the notion that the mask was to protect ME from being pelted with virus-laden droplets spewed out from some virus carrier. I was thinking that my mask would keep those droplets from entering my breathing apparatus, and keep me safe from harm. I thought the mask, like the seatbelt in my car, was all about ME.

The masks we are advised, and in some instances, MANDATED to wear are to keep US from infecting other people. And if they are not the right KIND of masks, worn and handled the right WAY, they are no more effective than that little black strip around the eyes that was meant to hide the Lone Ranger’s identity. Coronavirus Masks are meant to protect the rest of the world from the WEARER.

And I am distressed to tell you that the Centers for Disease Control, which we hark to here in the United States, and the World Health Organization (note the word WORLD) do NOT offer the same advice with regard to what kind of masks actually STOP any virus-laden droplets from spewing out into the world when we cough, or sneeze.

The Centers for Disease Control recommends a two layer mask. Go to THIS SITE to read their advice. It’s good advice, but is it enough?

https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/about-face-coverings.html

The Centers for Disease Control is a USA government entity that is part of the US Department of Health and Human Services. The Director is Robert Redfield, MD, who has served since March 26, 2018. He was appointed to the post by Donald Trump, after Trump’s first appointee, Tom Price, resigned over controversy regarding his use of private jets and charter flights at taxpayer expense.

The World Health Organization recommends a three-layer mask. Go to THIS SITE to read why “three layers are more effective than two.”

virus-2019/advice-for-public/when-and-how-to-use-masks

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health. The WHO Constitution states its main objective as “the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of health.” It is headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland, with six semi-autonomous regional offices and 150 field offices worldwide.

The Trump administration has begun the process of withdrawing the United States from the World Health Organization, effective July 6, 2021, via a letter sent to United Nations Secretary General António Guterres. It is not clear whether Trump can pull the United States out of the organization and withdraw funding without Congress. Democratic lawmakers have vowed to push back; Sen. Robert Menendez , the ranking Democrat on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, commented that such an action “leaves Americans sick & America alone.” Joe Biden has commented that, if elected, he would immediately rejoin the organization and “restore our leadership on the world stage, because Americans are safer when America is engaged in strengthening global health.”

TO DATE, the number of COVID-19 cases in the United States accounts for 23% of all cases in the world. Why is that?

TO DATE, the number of COVID-19 cases in the United States accounts for 23% of all cases in the world. Why is that?

Masking is obviously NOT enough – at least incorrect masks, worn incorrectly. It behooves us to know what we can do to protect ourselves, and others. One thing for sure – Trump’s resistance to wearing a mask himself because he “didn’t want to look like the Lone Ranger” was a fruitless worry on his part. He does not look like the Lone Ranger, no matter how hard he tries to separate the United States from the rest of the world.

» posted on Wednesday, September 2nd, 2020 by Linda Lou Burton

Hair Today

September 2, 2020, Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – It makes sense that Donald would comment on Nancy getting her hair blow dried; something a big hair guy would be sure to notice. Hard to tell if the hullabaloo is about Nancy walking down a hallway with wet hair and no mask, or the idea that blow driers in and of themselves are deadly. Geez, it’s hard to look pretty, with this virus thingy making a haircut so dangerous. I decided to check it out. What evil lurks in the hair salon these days? Beauty Parlor Gossip was the worst thing about such an environment in years past; Eudora Welty claimed to get some of her best story ideas from an afternoon under the drier. One of her short stories, The Petrified Man, is actually set in a

September 2, 2020, Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – It makes sense that Donald would comment on Nancy getting her hair blow dried; something a big hair guy would be sure to notice. Hard to tell if the hullabaloo is about Nancy walking down a hallway with wet hair and no mask, or the idea that blow driers in and of themselves are deadly. Geez, it’s hard to look pretty, with this virus thingy making a haircut so dangerous. I decided to check it out. What evil lurks in the hair salon these days? Beauty Parlor Gossip was the worst thing about such an environment in years past; Eudora Welty claimed to get some of her best story ideas from an afternoon under the drier. One of her short stories, The Petrified Man, is actually set in a  beauty parlor. Lots of gossip in that one. Yes, back before Twitter, we relied on our beauty parlors to spread tales.

beauty parlor. Lots of gossip in that one. Yes, back before Twitter, we relied on our beauty parlors to spread tales.

But back to our modern hair salons, and the dangers they may, or may not, present for us. Prevention magazine recently interviewed infectious disease specialist Michael Ben-Aderet, MD, about salon safety tips and recommendations in the age of COVID-19. The article appears at a time when many states are easing restrictions and businesses like hair salons are reopening.

“The number one-way coronavirus spreads is through respiratory droplets from someone who is sick,” said Ben-Aderet, explaining the virus spreads the same way in salons as it does anywhere – making it increasingly more important that sick people do not enter salons. “One way to do this is to screen clients before appointments to make sure those who are sick reschedule if they have fever, cough, or shortness of breath.” But many people want to know what happens if someone sick does enter a salon. Can products and tools like a blow dryer spread COVID-19?

“A blow dryer does have the potential to spread contaminated air around a room,” said Ben-Aderet. “But again, there needs to be an infected person around. Unless someone coughs into a hair dryer and that spreads the droplets, it’s very unlikely.” As for the blow dryer itself, Ben-Aderet says it’s “unlikely for a hair dryer to be contaminated with coronavirus.” He does explain, however, that while viruses can’t grow on surfaces, they can persist on certain surfaces for a particular amount of time, making it imperative that each salon is cleaned and disinfected after each client. “Touching a surface that is contaminated with secretions or mucus membranes from a sick individual and then touching your face can make you sick,” said Ben-Aderet. “It’s important to remember that viruses need to grow in a person.”

So there you have it. A sick PERSON is the dangerous thing. And if not yet obviously sick, A VIRUS CARRIER. If nobody is hauling the virus around on their body, and coughing and touching things with their virus-contaminated droplets, or hands they just wiped against their nose, there is no virus to get anybody else sick. And the notion of “sick people” spreading things to other people is true for ordinary colds, the flu, and lots of other stuff that people transmit from one to another. It’s rude to take your sick self out and put your germs off on somebody else. Don’t do it!

So there you have it. A sick PERSON is the dangerous thing. And if not yet obviously sick, A VIRUS CARRIER. If nobody is hauling the virus around on their body, and coughing and touching things with their virus-contaminated droplets, or hands they just wiped against their nose, there is no virus to get anybody else sick. And the notion of “sick people” spreading things to other people is true for ordinary colds, the flu, and lots of other stuff that people transmit from one to another. It’s rude to take your sick self out and put your germs off on somebody else. Don’t do it!

We’re advised to wear masks when we do go out now, so if we have that Virus Thingy, we don’t spread it. This is a dangerous proviso – having a mask dangling around your neck and not properly positioned, or made of the wrong material, or not kept clean, is as bad as not having one at all. Also, RELYING on a mask as your ultimate protection is foolhardy. Look at these videos showing how far DROPLETS can travel THROUGH a mask!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=evATiHUejxg&feature=youtu.be

Tomorrow: Masks Better Than Even The Lone Ranger Wore

» posted on Tuesday, September 1st, 2020 by Linda Lou Burton

That Virus Thingy

September 1, 2020, Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – Six months have passed since we really started counting “that virus thingy.” I check the US stats on the Centers for Disease Control website every week; so far no US state or territory has had a week go by with NO new cases. Except for American Samoa, bless their peaceful, well-isolated hearts. Today I took a worldwide look – the World Health Organization has an excellent site and really good advice. It’s vitally important to track what is going on in our own neighborhood, but I believe it is equally important to track what is happening beyond our borders. Compare – how are they managing? How are we, in the US?

for Disease Control website every week; so far no US state or territory has had a week go by with NO new cases. Except for American Samoa, bless their peaceful, well-isolated hearts. Today I took a worldwide look – the World Health Organization has an excellent site and really good advice. It’s vitally important to track what is going on in our own neighborhood, but I believe it is equally important to track what is happening beyond our borders. Compare – how are they managing? How are we, in the US?

As of the beginning of September, 2020, the World Health Organization shows 25,541,380 cases of COVID-19 reported worldwide; 852,000 deaths. If we want to compare that death count with the population of cities of equal size – we could say that EVERYBODY in Indianapolis, Indiana is dead now. Or, Seattle, Washington. Dead. No living, breathing persons left in those cities. When you look at it THAT way, it seems like a lot of deaths, doesn’t it? Other cities in the US that have populations in the 800,000 range are Charlotte, North Carolina; San Francisco, California, Columbus, Ohio; Forth Worth, Texas. Imagine them gone! Imagine a dystopian horror tale, such as Peter Heller’s The Dog Stars

As of the beginning of September, 2020, the World Health Organization shows 25,541,380 cases of COVID-19 reported worldwide; 852,000 deaths. If we want to compare that death count with the population of cities of equal size – we could say that EVERYBODY in Indianapolis, Indiana is dead now. Or, Seattle, Washington. Dead. No living, breathing persons left in those cities. When you look at it THAT way, it seems like a lot of deaths, doesn’t it? Other cities in the US that have populations in the 800,000 range are Charlotte, North Carolina; San Francisco, California, Columbus, Ohio; Forth Worth, Texas. Imagine them gone! Imagine a dystopian horror tale, such as Peter Heller’s The Dog Stars  (2012); a world where the unexpected happened – a flu pandemic struck – and life on the planet had to adjust to “what is.” While I’m a believer in Positive Thinking, I’m also a believer in being well-informed. And approaching life in ways that are reasonable, and not based on impatience to “get back to normal, now!” Like, opening schools. Sure, kids are getting a sucky education right now. Sure, parents are sick and tired of having to manage and monitor their children’s schooling from home. Sure – well the issue is ablaze in arguments and accusations and vastly different proposals. Politics involved. What is the best solution? Start with facts.

(2012); a world where the unexpected happened – a flu pandemic struck – and life on the planet had to adjust to “what is.” While I’m a believer in Positive Thinking, I’m also a believer in being well-informed. And approaching life in ways that are reasonable, and not based on impatience to “get back to normal, now!” Like, opening schools. Sure, kids are getting a sucky education right now. Sure, parents are sick and tired of having to manage and monitor their children’s schooling from home. Sure – well the issue is ablaze in arguments and accusations and vastly different proposals. Politics involved. What is the best solution? Start with facts.

Here are the numbers broken down by sections of the world, and then the US.

World Health Organization Statistics – Number of Cases Reported Worldwide as of September 1, 2020

- Americas – 13,469,747

- SE Asia – 4,318,281

- Europe – 4,225,328

- Eastern Mediterranean – 1,939,204

- Africa – 1,056,120

- Western Pacific – 501,959

- TOTAL WORLDWIDE – 25,541,380

Of the Americas, that’s both North and South, let’s look at what is happening just in the United States. We’ve got the most cases of any American country — 6,004,443 COVID-19 cases reported to date; 183,050 deaths from the virus. That “death” total kills off everybody in Little Rock, just about! The US numbers are big, and continue to get bigger. Over the next month, I’ll be looking at what other countries in the world are doing to combat a pandemic that is “sure ‘nough” real, and how they are keeping their citizens safe.

Meanwhile, wash your hands, keep your chin up (with MASK intact!), and if you happen to live in any of the states below, get in touch with your governor because your state is leading the pack this week, an honor you don’t want.

US States With Highest Percent of Population Diagnosed With COVID-19 as of September 1

- Louisiana – 3.2%, Governor John Bel Edwards, Democrat

- Florida – 2.87%, Governor Ronald Dion DeSantis, Republican

- Mississippi – 2.81%, Governor Jonathon Tate Reeves, Republican

- Arizona – 2.77%, Governor Douglas Anthony Ducey, Republican

- Alabama – 2.57%, Governor Kay Ellen Ivey, Republican

US States With Greatest Numbers of COVID-19 Cases Diagnosed as of September 1

- California – 704,485, Governor Gavin Christopher Newsom, Democrat

- Florida – 616,629, Governor Ronald Dion DeSantis, Republican

- Texas – 612,969, Governor Gregory Wayne Abbott, Republican

- New York – 435,783, Governor Andrew Mark Cuomo, Democrat

- Georgia – 270,471, Governor Brian Porter Kemp, Republican

US States With Most New Cases Diagnosed in One Week as of September 1

- California – 40,416, Governor Gavin Christopher Newsom, Democrat

- Texas – 35,432, Governor Gregory Wayne Abbott, Republican

- Florida – 22,342, Governor Ronald Dion DeSantis, Republican

- Georgia – 16,522, Governor Brian Porter Kemp, Republican

- Illinois – 15,130, Governor Jay Robert “J. B.” Pritzker, Democrat