» posted on Sunday, July 7th, 2024 by Linda Lou Burton

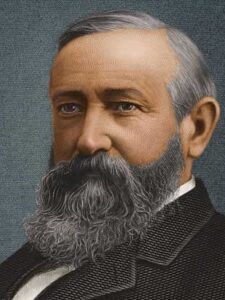

#23. Harrison, Benjamin

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – Benjamin Harrison VIII (August 20, 1833 – March 13, 1901) was the 23rd president of the United States from 1889 to 1893. The history books tell you he was “a member of the Harrison family of Virginia,” but I’m telling you he’s your ace ticket for scoring big trivia points with the Harrison name. It pops up everywhere! His great-grandfather Benjamin Harrison V (1726-1791) was a Founding Father who signed the Declaration of Independence. I looked it up, his signature is right under that other famous Virginian, Th Jefferson, in the section below John Hancock. And his grandfather was the ninth President of the United States. For one whole month. Yes, William Henry Harrison (1773-1841) was the first president to die in office and served the shortest term of any president in history. His inaugural speech was the longest ever delivered; and at 68 he was the oldest man (at that time) to ever take office. One of William Henry’s ten children was John Scott Harrison (1804-1878), who represented the state of Ohio for a couple of terms in Congress, dabbling in politics and farming and fathering thirteen children. And one of his children was – yep – Benjamin Harrison VIII. Just think – John’s father was President of the United States and John’s son was President of the United States. That gives him bragging rights not one other person can claim. The Harrison name meant one thing for sure – anyone born with it had a lot to live up to.

What kind of man did Benjamin VIII turn out to be? Actually a pretty nice, well rounded, family oriented fellow. Not only his children lived in the White House with him and First Lady Caroline, but his grandchildren too. One of the most bandied-about stories of his White House residency reports Benjamin holding on to his top hat while chasing a runaway goat down Pennsylvania Avenue. “Old Whiskers” was his grandchildren’s pet, and every afternoon was playtime on the White House lawn. Until that day the goat took off with the grandkids!

What kind of man did Benjamin VIII turn out to be? Actually a pretty nice, well rounded, family oriented fellow. Not only his children lived in the White House with him and First Lady Caroline, but his grandchildren too. One of the most bandied-about stories of his White House residency reports Benjamin holding on to his top hat while chasing a runaway goat down Pennsylvania Avenue. “Old Whiskers” was his grandchildren’s pet, and every afternoon was playtime on the White House lawn. Until that day the goat took off with the grandkids!

The Long and Winding

“Old Whiskers” was just one of many “runaway goats” Benjamin faced during those four White House years, which was a place he never really sought to be. How did he wind up there? A long and winding road, it seems, with an overriding theme. Benjamin followed the good course, dutifully fitting in as he perceived what was expected of him. He was the second-born of ten children, a big-brother role; and, as his parents wanted him to have a good education, he studied. First in a log-cabin schoolhouse, then at age fourteen he and big brother Irwin enrolled at Farmer’s College in Cincinnati where he met Caroline Lavinia Scott; her father  was a professor there, and a Presbyterian minister. In two years he transferred to Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, joined Phi Delta Theta and Delta Chi (a law fraternity), and joined the Presbyterian church.

was a professor there, and a Presbyterian minister. In two years he transferred to Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, joined Phi Delta Theta and Delta Chi (a law fraternity), and joined the Presbyterian church.

In 1852 he graduated and began to study law with Judge Bellamy Storer in Cincinnati; in 1853 he married Caroline (her father performed the ceremony) and in 1854 he was admitted to the Ohio Bar, sold some property he’d inherited and moved to Indianapolis, began practicing law, and had a son! (Russell Harrison). At that point – do the math – he was just 21 years old.

The years ticked on – he and Caroline were active in the church; in 1856 he joined the newly formed Republican party; in 1857 he was elected city attorney for Indianapolis; in 1858 daughter Mary was born. It was a sensible life, on track. In 1860 he established a new law partnership with William Fishback; but note the year. 1860, and the beginning of war.

If I Can Be Of Service

When Lincoln called for more recruits for the Union Army in 1862, Benjamin struggled with the idea – should he answer the call, or take care of his young family? But he told Ohio’s governor Oliver Morton “If I can be of service, I will go.” He was asked to recruit a regiment, which he did. He was commissioned as a captain and company commander in July of 1862.  By August Morton commissioned him colonel, the 70th Indiana was mustered into service, and the regiment left to join the Union Army at Louisville, Kentucky.

By August Morton commissioned him colonel, the 70th Indiana was mustered into service, and the regiment left to join the Union Army at Louisville, Kentucky.

Benjamin fought in the Battles of Resaca, New Hope Church, Kennesaw Mountain, Marietta, Peachtree Creek, Atlanta, and as Sherman continued his march, the Battle of Nashville. Lincoln nominated him to the grade of brevet (honorary) Brigadier General of volunteers in January 1865. On April 9 a Union victory was declared and Benjamin mustered out with the 70th Indiana on June 8, 1865. He returned home after serving with honor, and without injury.

Back To Lawyering. Plus.

Over the next 20 years Benjamin built up a reputation as one of Indiana’s leading lawyers. He ran for Governor (didn’t win); he ran for Senator (and won, once). He made speeches on behalf of Republican candidates. He made money. And, next thing you know, it’s 1888 and there he is on the Republican ticket. He won. He didn’t get the most POPULAR votes, remember. But it’s those ELECTORAL votes that claim the winner. His inauguration was big fun, he kept his speech much shorter than his granddad did; and John Philip Sousa’s Marine Band played at the Inaugural Ball that evening. The Harrison family was In Again. But Benjamin didn’t much like “in.” He was hounded by job seekers, particularly those who expected rewards for their campaign support. Benjamin had made no political bargains, but his supporters had made many pledges on his behalf. Benjamin hated the constant nab and grab atmosphere, in fact, he even complained about his office space: “There is only a door—one that is never locked—between the president’s office and what are not very accurately called his private apartments.”

Well then. Enter Caroline.

First Lady Caroline didn’t care much for the White House either. She refused the “meet and greet” hostessing duties, leaving those to daughter Mary and daughter-in-law Mary while she continued her extensive charity work, artistic pursuits, and general domestic surveillance. The White House was in terrible condition when the Harrisons moved in – floors were rotted out, rats scurried everywhere, and there was only one bathroom for the family to use! The Harrison crew was huge – in addition to Benjamin and Caroline, their two children Russell (35) and Mary (31) lived there with their families; it was also home to Caroline’s father, sister, and widowed niece Mary Scott Dimmick (31), who served as Caroline’s assistant.

Caroline took particular issue with the fact that room arrangements allowed visitors access to family quarters. She wanted to reconstruct the White House, drawing new plans with architect Frederick Owen. But Congress would not fund it, allocating $35,000 for updating instead. She consulted with Thomas Edison to bring electricity into the White House, but he concluded the building wasn’t safe enough in its present state to incorporate the wiring.

With the allocated funds Caroline moved ahead; she had all rooms repainted and carpets and upholstery replaced. She purchased new furniture. She had a heating system and more bathrooms installed and the kitchen modernized. Some electrical wiring was installed to supplement the gas lighting. As to the rat problem – ferrets were released to take care of that. Caroline was on a roll: the musty old basement was redone with concrete floors and tiled walls; the Green Room was redone in rococo style. By the time she finished, she had redone everything. And with a clever marketing eye, she arranged publicity photos including her very popular grandchildren against the backdrop of all this prettiness. Overall, Caroline genuinely cared about the White House. She had all White House furniture accounted for, and documented the history of every item. She ended the practice of selling off furnishings at the end of an administration – like the Resolute Desk, which still serves presidents to this day.

And Just Like That

Caroline’s list of accomplishments is astonishing. She supported women’s rights. She supported education. She raised funds for the Johns Hopkins University Medical School on the condition that it admit women, which it did – the first in the US to do so. She co-founded the Daughters of the American Revolution. She was the first First Lady to make a public speech. And in the midst of it all, on October 25, 1892, just two weeks before Benjamin was defeated for reelection, Caroline died. She’d spent the summer in the Adirondacks after her diagnosis of tuberculosis; her weakening condition affected the presidential campaign. Was it tuberculosis that ultimately killed her, or suspicion? Hold that thought.

Historians today credit Benjamin with doing more to move the nation along the path to world empire than any other, setting the agenda for the next thirty years of foreign policy. He began to build up the Navy – the USS Texas in 1892 was the country’s first battleship; a total of seven ships were started during this period. The country grew – six far west states were admitted to the Union during his presidency – Washington, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, North and South Dakota.

But he also chased a lot of “runaway goats” (while holding onto his hat?) as he and what became known as his Billion Dollar Congress failed to recognize the massive industrial changes and economic hardships that existed, causing railroads and banks and businesses to topple within days of his retirement.

It was a mess. And Grover Cleveland, the Veto Guy, was back in.

Regrets?

Remember my comment about Caroline’s death? That word “suspicion”? Well, Benjamin went on to marry Mary Scott Dimmick. Remember her, Caroline’s widowed niece? The one Caroline brought to the White House as her personal assistant? Some say Mary Dimmick’s romance with Benjamin began while he was in the White House. Did it? We know that Benjamin went back to Indianapolis when he left the White House in 1893, then lived in San Francisco for a while, giving lectures on law at Stanford University. He served on the Board of Trustees at Purdue University, wrote articles about the Federal government, published a book. He didn’t marry Mary until 1896.

Whatever the truth, Benjamin’s children were horrified. They refused to attend the wedding and were never close again. Did Benjamin give a hoot? Maybe not. Maybe he was enjoying his new life free from the expectations he’d dealt with for so many years. He and Mary had a baby right away, daughter Elizabeth. And Benjamin stayed busy doing lawyering things. Worldwide. My gosh, he attended the First Peace Conference at the Hague in 1899; he served on a special committee for creed revision in the national Presbyterian General Assembly. He kept going, clear up to his death in Indianapolis March 13, 1901 from pneumonia.

Side by Side

Benjamin was buried in Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis beside Caroline. Mary lived another 47 years in Indianapolis, in the house from which Caroline hosted the “front porch speeches” that helped Benjamin get elected president. When Mary died in 1948, she was buried in Crown Hill Cemetery, alongside Benjamin. And Caroline.

Would I invite Benjamin to my party? Probably not. He was a hardworking man but seemed to focus on doing what he thought people expected him to do. And that very quality might cause a problem. I mean – which wife would he bring?