» posted on Tuesday, July 9th, 2024 by Linda Lou Burton

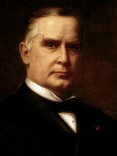

#25. McKinley, William

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – William McKinley (January 29, 1843 – September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. William was one of seven presidents who rendered some type of service in the Civil War. I’m going to tell you what he did at Antietam, I mean, he just up and DID IT without being ordered. But first, what nudged William McKinley to volunteer for service? What was he doing, and what was happening around him? William was born in Ohio January 29, 1843, the seventh of William and Nancy Allison McKinley’s nine children. His father owned a small iron factory, and, it is said, instilled a strong work ethic in his children. His mother was devoutly religious, teaching her children the value of prayer, and honesty. There was fun stuff going on in the McKinley household, like fishing and hunting and swimming, but also a strong focus on education. William spent some time in college, but when family finances declined, took a job as a postal clerk. He was 18 on April 15, 1861 when, three days after an attack on Fort Sumter, President Lincoln issued a proclamation calling forth the state

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – William McKinley (January 29, 1843 – September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. William was one of seven presidents who rendered some type of service in the Civil War. I’m going to tell you what he did at Antietam, I mean, he just up and DID IT without being ordered. But first, what nudged William McKinley to volunteer for service? What was he doing, and what was happening around him? William was born in Ohio January 29, 1843, the seventh of William and Nancy Allison McKinley’s nine children. His father owned a small iron factory, and, it is said, instilled a strong work ethic in his children. His mother was devoutly religious, teaching her children the value of prayer, and honesty. There was fun stuff going on in the McKinley household, like fishing and hunting and swimming, but also a strong focus on education. William spent some time in college, but when family finances declined, took a job as a postal clerk. He was 18 on April 15, 1861 when, three days after an attack on Fort Sumter, President Lincoln issued a proclamation calling forth the state  militias in order to suppress the rebellion. Thousands of Ohioans began volunteering; he and cousin William Osbourne joined up as privates in their hometown Guard that June. The Guard soon headed for Columbus and was consolidated with other units to form the 23rd Ohio Infantry.

militias in order to suppress the rebellion. Thousands of Ohioans began volunteering; he and cousin William Osbourne joined up as privates in their hometown Guard that June. The Guard soon headed for Columbus and was consolidated with other units to form the 23rd Ohio Infantry.

When William mustered out of the Army in July 1865, his rank was brevet (honorary) Major and his list of stories so long he wound up with a book. That is, a diary; 72 pages of which are now preserved in the Ohio History Collections, note: The diary details his service with Company E of the 23rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry at Camp Jackson in Ohio and throughout Virginia. He mentions daily activities, including drill, visits, prayer meetings, and troop movements, … (he)also writes in detail about the Battle of Carnifex Ferry, his first major battle, including his fears and the actions of Major Rutherford B. Hayes, another future president.

He Wrote Stuff Down!

You know right away I’d invite this man to my party, just to talk about that diary. I’d definitely ask him about Antietam. In case you forgot your American history, the Battle of Antietam was a key turning point in the Civil War. The battle pitted Union General George McClellan against General Robert E. Lee’s Army and lasted 12 hours, resulting in 23,000 soldiers killed, wounded, or missing. It was the bloodiest single-day battle in American history, ending the Confederate Army’s first invasion into the North and leading Abraham Lincoln to issue the  preliminary Emancipation Proclamation.

preliminary Emancipation Proclamation.

What 19-year-old William did that day isn’t a swashbuckling tale, but it was heroic in its simplicity. Major Rutherford Hayes, leader of the 23rd Ohio Infantry that day, described it this way: “Early in the afternoon, naturally enough, with the exertion required of the men, they were famished and thirsty, and to some extent broken in spirit. The commissary department of that brigade was under Sergeant McKinley’s administration and personal supervision. From his hands every man in the regiment was served with hot coffee and warm meats…. He passed under fire and delivered, with his own hands, these things, so essential for the men for whom he was laboring.” Today a monument in Antietam National Battlefield marks the spot, and honors William McKinley’s actions.

Death Can Be Fickle

William walked through fire at Antietam without injury. He fought to the end of a bloody war without injury (although once his horse was shot out from under him). But on September 6, 1901, at the Temple of Music during the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York, Leon Czolgosz walked up to him, pulled a gun he’d concealed with a handkerchief, and shot President William McKinley twice in the abdomen.

William was taken to the exposition aid station, urging his helpers to call off the mob that had set upon Czolgosz. Doctors were unable to find the second bullet, and William was moved to the home of John Milburn, president of the Pan-American Exposition Company, where he seemed to improve over the next few days. Members of his cabinet, who had rushed to Buffalo when hearing the news, dispersed; Vice President Roosevelt went ahead with a planned camping trip. Meanwhile, gangrene was growing on the walls of William’s stomach and slowly poisoning his blood. By the evening of the 13th, after drifting in and out of consciousness all day, he said “It is useless, gentlemen. I think we ought to have prayer.” As friends and relatives gathered around his bed, a sobbing First Lady Ida softly sang his favorite hymn. His final act was to comfort her. He died at 2:15 AM September 14.

Theodore Roosevelt rushed back to Buffalo and took the oath of office as the 26th president of the United States. Czolgosz, who claimed to be an anarchist, was put on trial for murder nine days later, and executed by electric chair October 29.

About Ida

Ida Saxton McKinley’s story is more ironically sad than William’s; I keep studying it and wondering how bright fortune could switch to such dark tragedy. Better get your hanky out before you read further. Born June 8, 1847 into one of Canton, Ohio’s wealthiest families, Ida and her siblings Mary and George grew up in the grand Saxton House. Parents James and Kate strongly believed in equal education for women; Ida was sent to good schools and excelled in her studies, a gifted scholar. She attended opera performances, classical music concerts, theatrical plays. She was inspired by one of her teachers to take long walks every day to build up physical fitness – a progressive idea at the time. On a grand tour of Europe after graduating, Ida and sister Mary hiked the Alps. Ida’s father hired her to work at his bank – a typically males-only environment; she was so proficient she often managed the bank in her father’s absence. That’s where she was working when she met William. I’ll come back to that.

Ida Saxton McKinley’s story is more ironically sad than William’s; I keep studying it and wondering how bright fortune could switch to such dark tragedy. Better get your hanky out before you read further. Born June 8, 1847 into one of Canton, Ohio’s wealthiest families, Ida and her siblings Mary and George grew up in the grand Saxton House. Parents James and Kate strongly believed in equal education for women; Ida was sent to good schools and excelled in her studies, a gifted scholar. She attended opera performances, classical music concerts, theatrical plays. She was inspired by one of her teachers to take long walks every day to build up physical fitness – a progressive idea at the time. On a grand tour of Europe after graduating, Ida and sister Mary hiked the Alps. Ida’s father hired her to work at his bank – a typically males-only environment; she was so proficient she often managed the bank in her father’s absence. That’s where she was working when she met William. I’ll come back to that.

Two things in Ida’s early life caught my attention. One was the confidence her father placed in her; surely this bolstered her belief in possibilities. The other relates to a limbless artist who painted with his mouth she met in Amsterdam when she and sister Mary were on that European tour. Was this what inspired her to insist on living a full public life despite disabilities she developed later? Yes, disabilities.

Life With William

In 1870 Ida and William began serious courting; they were married January 25, 1871; (she was 23, he was 27) in a service attended by a thousand people. Ida was, after all, considered the belle of Canton, Ohio. Their first child, Katherine, was born on Christmas day that year. ”Katie” became the center of the household; Ida became pregnant again. About two weeks before the new baby’s birth Ida’s mother died of cancer; at the burial service Ida fell and struck her head while stepping out of a carriage. After a difficult delivery, the baby, a girl who  was sickly from the start, died within four months. Obsessed with fear of losing her firstborn child too, Ida spent her days in a darkened room, weeping. And the worst happened. On June 24, 1875, Katie died.

was sickly from the start, died within four months. Obsessed with fear of losing her firstborn child too, Ida spent her days in a darkened room, weeping. And the worst happened. On June 24, 1875, Katie died.

Ida was plunged into a deep depression. Historians believe she became immunocompromised during that second pregnancy, which led to epileptic seizures. As her seizures worsened, she ate very little and prayed for her own death. William did everything he could to help her regain her “interest in existence,” offering to give up his political ambitions for her. But Ida insisted that he continue his increasingly successful career.

Tracking William

After mustering out of the Army in 1865, William decided to pursue a career in law. He studied with an attorney, then attended Albany Law School; in March 1867 he was admitted to the Ohio Bar and moved to Canton where he formed a partnership with George Belden, an experienced lawyer. And remember William’s connection with Rutherford Hayes that began during the war? They stayed friends, and when Rutherford was nominated for governor in 1867, William made speeches on his behalf. That edged him into politics.

In 1869 he ran for the office of prosecuting attorney and was elected. In 1876, the year after Katie’s death, he followed Ida’s urging to stay on his chosen path – he campaigned for a congressional seat while campaigning for Rutherford Hayes for president. Both William and Rutherford won.

- 1877-1883 Congressman US House of Representatives

- 1885-1891 Congressman US House of Representatives

- 1892-1896 Governor of Ohio

- 1897-1901 President of the United States

William’s inauguration as the 25th president took place March 4, 1897 in front of the Old Senate Chamber at the capitol. And yes, Ida was there. She was present at the inaugural ball that evening too, wearing a lavish gown that made all the news. But, accompanied by William, she left early. This set the stage; Ida’s attendance at functions thereafter was sporadic due to the unpredictability of her seizures. William took great care to accommodate Ida’s condition. At state dinners she sat beside him rather than, as was tradition, at the opposite end of the table. William kept a handkerchief in his pocket so that in case of a seizure he could cover her contorted face. Once it passed, he’d remove the handkerchief and go on, as though nothing had happened.

William’s inauguration as the 25th president took place March 4, 1897 in front of the Old Senate Chamber at the capitol. And yes, Ida was there. She was present at the inaugural ball that evening too, wearing a lavish gown that made all the news. But, accompanied by William, she left early. This set the stage; Ida’s attendance at functions thereafter was sporadic due to the unpredictability of her seizures. William took great care to accommodate Ida’s condition. At state dinners she sat beside him rather than, as was tradition, at the opposite end of the table. William kept a handkerchief in his pocket so that in case of a seizure he could cover her contorted face. Once it passed, he’d remove the handkerchief and go on, as though nothing had happened.

Stop! Reread that sentence! Does that sound a little bit like Antietam to you? No matter what the surrounding circumstances, recognizing someone’s need, and taking care of it? Well, you might say, why didn’t he just hide the poor woman away and ignore the problem; or why didn’t she just stay the hell in a darkened room?

William and Ida just didn’t do things that way. And William was elected for a second term.

The unemployment rate had dropped from 14.5% in 1896 to 5% in 1900. William was seen as a “victorious commander in chief” due to the Spanish-American war. Was campaign strategy the determining factor in winning a second term? Or was it character? Probably a little bit of all. But think back to Antietam and how he got hot coffee to his men, and those state dinners and how he cared for Ida; well, he just DID it. He didn’t back off, or hide from a situation. During his presidency he invited the press to regular briefings. He traveled widely attending public ceremonies and meeting his constituency. He was not a charismatic leader, but people who knew him generally liked him. What a sad, sad loss that September day.

The unemployment rate had dropped from 14.5% in 1896 to 5% in 1900. William was seen as a “victorious commander in chief” due to the Spanish-American war. Was campaign strategy the determining factor in winning a second term? Or was it character? Probably a little bit of all. But think back to Antietam and how he got hot coffee to his men, and those state dinners and how he cared for Ida; well, he just DID it. He didn’t back off, or hide from a situation. During his presidency he invited the press to regular briefings. He traveled widely attending public ceremonies and meeting his constituency. He was not a charismatic leader, but people who knew him generally liked him. What a sad, sad loss that September day.

The memorials.

Ida was 54 when her husband died that day in Buffalo. Somehow she maintained the strength to stay by his side those seven days after he was shot, but could not bring herself to attend his funeral. She visited William’s grave every day until her death May 26, 1907. In Canton today you can visit the McKinley Memorial Mausoleum and the graves of William, Ida, Katie, and baby Ida; as well as the Saxton House, now a First Ladies National Historic Site.

Ida was 54 when her husband died that day in Buffalo. Somehow she maintained the strength to stay by his side those seven days after he was shot, but could not bring herself to attend his funeral. She visited William’s grave every day until her death May 26, 1907. In Canton today you can visit the McKinley Memorial Mausoleum and the graves of William, Ida, Katie, and baby Ida; as well as the Saxton House, now a First Ladies National Historic Site.

And don’t forget Antietam, there in Maryland.