» posted on Wednesday, July 3rd, 2024 by Linda Lou Burton

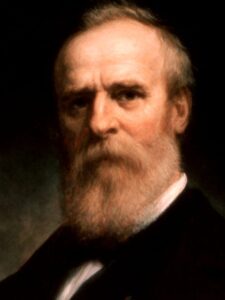

#19. Hayes, Rutherford Birchard

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – Rutherford Birchard Hayes (October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was the 19th president of the United States, from 1877 to 1881. He was the first president to graduate from law school – Harvard Law School at that; the only one of the seven presidents who served in the Civil War who was wounded (more than once); and the first president to come into office after losing the popular vote. In fact, he almost wasn’t president at all. Remember, the country was still in a period of distress and reconstruction when Grant declined a third term.

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – Rutherford Birchard Hayes (October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was the 19th president of the United States, from 1877 to 1881. He was the first president to graduate from law school – Harvard Law School at that; the only one of the seven presidents who served in the Civil War who was wounded (more than once); and the first president to come into office after losing the popular vote. In fact, he almost wasn’t president at all. Remember, the country was still in a period of distress and reconstruction when Grant declined a third term.

On November 11, 1876, three days after election day, Democrat Tilden appeared to have won 184 electoral votes, one short of a majority. Republican Hayes appeared to have 166, with the 19 votes of Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina still in doubt. After an Electoral Commission declared Hayes the victor, outraged Democrats attempted a filibuster to prevent Congress from accepting the findings. It took a compromise to move forward, a big compromise, which essentially stated that Democrats would acknowledge Hayes as president only if certain demands were met:

- Removal of all remaining US military forces from Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina.

- Appointment of at least one Southern Democrat to Hayes’ cabinet.

- Construction of another transcontinental railroad using the Texas and Pacific in the South.

- Legislation to help industrialize the South and restore its economy.

On March 2, the filibuster ended, and on Saturday, March 3, Rutherford Hayes became the first president to be sworn in at the Red Room of the White House. This ceremony was held in secret under tight security, due to the bitter divisiveness of the election. The public ceremony took place on Monday, March 5, at the East Portico of the Capitol. The Presidential Oath of  Office, in case you don’t know, is “I do solemnly swear that I will faithfully execute the Office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.” That is what Rutherford said that day, but when I review what he did for the next four years, and for all the years before, and after, I’m reminded of the Boy Scout Oath — I will do my best to do my duty to God and my country….to help other people at all times; to keep myself physically strong, mentally awake, and morally straight.

Office, in case you don’t know, is “I do solemnly swear that I will faithfully execute the Office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.” That is what Rutherford said that day, but when I review what he did for the next four years, and for all the years before, and after, I’m reminded of the Boy Scout Oath — I will do my best to do my duty to God and my country….to help other people at all times; to keep myself physically strong, mentally awake, and morally straight.

And his wife Lucy was just the same. Yes, I’d invite them both to my party, and hope we’d become lifelong friends. Just listen to the way they lived their lives.

Before

Rutherford Hayes had something in common with Andrew Jackson – his father died just weeks before he was born, and his mother never remarried. But the resemblance to their path to the presidency ends there. Sophia Hayes raised daughter Fanny and son Rutherford with the help of her brother, Sardis Birchard. Both the Hayes and Birchard families were descended from New England colonists – hardy stock. Rutherford was born in Delaware, Ohio and first went to common schools there; then to Webb School in Connecticut, a preparatory school where he studied Latin and Greek. Back to college in Ohio where he earned highest honors – graduating as class valedictorian. By then, he’d gotten interested in politics. So next step – Harvard Law School, of course. The year was 1843; Rutherford was 21  when he decided on that path. He was 23 when he graduated, was admitted to the Ohio bar, and opened his own law office.

when he decided on that path. He was 23 when he graduated, was admitted to the Ohio bar, and opened his own law office.

A move to Cincinnati in 1850 put him just across the river from the slave state of Kentucky, and his focus changed from dealing primarily with commercial issues to criminal law. Ohio was a destination for escaping slaves, and Rutherford defended slaves who had been accused under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. He became a successful criminal defense lawyer and found the work personally gratifying, but it also was politically useful, as it raised his profile in the Republican Party. And socially, he joined the Literary Society, attended the Episcopal Church, and courted Lucy Webb. They married December 30, 1852 at her mother’s house – he was 30, she was 21.

I Love Lucy

Lucy Webb (1831-1889) and Rutherford Hayes first met at Ohio Wesleyan University. Lucy was 14. Yes, she was a smart girl, in fact, the first First Lady to have a college degree. She was too young for Rutherford at 14 (he was 23), but when they met again in Cincinnati, things changed. Lucy and Rutherford were members of the same wedding party the summer she was 19. It was one of those affairs where a gold ring was baked into the wedding cake as a prize. Perhaps a tradition like the bride tossing her bouquet? Rutherford got the piece of cake that had the ring, and he gave it to Lucy. After the two were engaged, she returned the ring to him, and he wore it for the rest of his life.

Too sentimental for a criminal defense lawyer who became president? Listen to what he wrote in his diary about her in 1851: “I guess I am a great deal in love with L(ucy). … Her low sweet voice … her soft rich eyes….She sees at a glance what others study upon….She is a genuine woman, right from instinct and impulse rather than judgment and reflection.”

And Then There Was a War

Rutherford was lukewarm about the idea of a civil war; as states began to secede after Lincoln’s election, his opinion was to “let them go.” His feelings changed after the attack on Fort Sumter however; he joined a volunteer company composed of his Literary Society friends. Things moved rapidly; he was promoted to major in the 23rd Regiment of Ohio Volunteer Infantry; the 23rd was assigned to western Virginia. War Hero stories now – Rutherford led several raids against rebel forces; sustained a knee injury and later, in northern Virginia, was shot through his left arm, fracturing the bone. With a handkerchief tied above the wound to stop the bleeding, he continued to lead his men. Hospitalized for a bit, he was back in the thick of it; the Shenandoah Valley Campaigns of 1864; Rutherford took a bullet to the shoulder; had a horse shot out from under him; and kept going. Victory after victory as they broke through Confederate lines; an ankle sprain when thrown from a horse; a bullet to his head from a spent round. His leadership and bravery drew attention; Grant wrote of him: “His conduct on the field was marked by conspicuous gallantry as well as the display of qualities of a higher order than that of mere personal daring.” In May of 1865 the 23rd returned to Ohio to be mustered out of service.

Rutherford was lukewarm about the idea of a civil war; as states began to secede after Lincoln’s election, his opinion was to “let them go.” His feelings changed after the attack on Fort Sumter however; he joined a volunteer company composed of his Literary Society friends. Things moved rapidly; he was promoted to major in the 23rd Regiment of Ohio Volunteer Infantry; the 23rd was assigned to western Virginia. War Hero stories now – Rutherford led several raids against rebel forces; sustained a knee injury and later, in northern Virginia, was shot through his left arm, fracturing the bone. With a handkerchief tied above the wound to stop the bleeding, he continued to lead his men. Hospitalized for a bit, he was back in the thick of it; the Shenandoah Valley Campaigns of 1864; Rutherford took a bullet to the shoulder; had a horse shot out from under him; and kept going. Victory after victory as they broke through Confederate lines; an ankle sprain when thrown from a horse; a bullet to his head from a spent round. His leadership and bravery drew attention; Grant wrote of him: “His conduct on the field was marked by conspicuous gallantry as well as the display of qualities of a higher order than that of mere personal daring.” In May of 1865 the 23rd returned to Ohio to be mustered out of service.

Government Positions

- Member of U.S. House of Representatives, 1865-67

- Governor of Ohio, 1868-72

- Governor of Ohio, 1876-77

- 19th President of the United States, 1877-1881

As a president coming into office with a Congress full of angry Democrats, Rutherford fought for several things that didn’t happen.

- “My task is to wipe out the color line, to abolish sectionalism, to end the war and bring peace,” he wrote in his diary. His efforts failed to persuade the South to accept legal racial equality or to convince Congress to appropriate funds to enforce the civil rights laws.

- Civil service appointments had been based on the spoils system since Andrew Jackson’s presidency. Believing that federal jobs should be awarded by merit according to an examination, he was unable to convince Congress, but did issue an executive order forbidding federal office holders from being required to make campaign contributions or taking part in party politics.

Rutherford may have been blocked by Congress, but Lucy definitely made headway with things in the White House. Imagine moving into the White House after the war years –it was a mess! Lucy scrounged around in the attic and rearranged things to hide the holes in the carpets and drapes. Significant changes made to the White House during Hayes’ term were the installation of bathrooms with running water, but the biggest change involved the “billiard room,” a room that connected the house with the greenhouse conservatories. Lucy put the  billiard table in the basement, opened the shuttered windows in the State Dining Room, and enlarged the greenhouses, offering guests a beautiful view. Every day flowers were brought in from the greenhouses to decorate the White House, and additional bouquets were sent to Washington hospitals.

billiard table in the basement, opened the shuttered windows in the State Dining Room, and enlarged the greenhouses, offering guests a beautiful view. Every day flowers were brought in from the greenhouses to decorate the White House, and additional bouquets were sent to Washington hospitals.

Music was important to Lucy. Not only did famous musicians perform at White House events downstairs; they had informal “sings” upstairs in the family quarters. Lucy sang and played the guitar; the vice president and various cabinet members often played the piano and sang gospel songs. In general, Lucy had a casual family style; during the holidays, she invited staff members and their families to Thanksgiving dinner and opened presents with them on Christmas morning. Lucy allowed White House servants to take time off to attend school.

Lucy was the first First Lady to use a typewriter, a telephone, and a phonograph while in office. And she was fond of animals – a cat, a bird, two dogs and a goat were part of the Hayes family; remember, son Scott was 6 and daughter Fanny 10 at the time they moved in; three older sons were 19, 21 and 24. Reporters loved to write about Lucy; an article in the New York Herald said of her: “Mrs. Hayes is a most attractive and lovable woman. She is the life and soul of every party … For the mother of so many children she looks … youthful.”

Note: the White House during the Hayes’ stay was alcohol free. Rutherford made that decision early on, dismayed by drunken behavior he’d observed at receptions around Washington.

After

Rutherford kept his promise to serve only one term and the Hayes family returned to their Fremont, Ohio home, Spiegel Grove, in 1881. He became an advocate for educational charities and federal education subsidies for all children. He believed education was the best way to heal the rifts in American society and allow people to improve themselves. He emphasized the need for vocational, as well as academic, education: “I preach the gospel of work,” he wrote, “I believe in skilled labor as a part of education.” In 1889 he gave a speech encouraging black students to apply for scholarships from the Slater Fund, one of the charities with which he was affiliated. One such student, W. E. B. Du Bois, received a scholarship in 1892.

Lucy joined the Woman’s Relief Corps, attended reunions of the 23rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry, and entertained visitors to Spiegel Grove. She also became national president of the newly formed Woman’s Home Missionary Society of the Methodist Church. As president, she called attention to the plight of the urban poor and disenfranchised African-Americans in the South. She also spoke out against Mormon polygamy.

Lucy died on June 25, 1889 after suffering a stroke. She was 57 years old. Rutherford died of a heart attack on January 17, 1893, at the age of 70. They are buried side by side at Spiegel Grove. Also buried there is their dog Gryme and two horses — Old Whitey and Old Ned.

Lucy died on June 25, 1889 after suffering a stroke. She was 57 years old. Rutherford died of a heart attack on January 17, 1893, at the age of 70. They are buried side by side at Spiegel Grove. Also buried there is their dog Gryme and two horses — Old Whitey and Old Ned.

Good Scouts, to the end.