» posted on Friday, July 5th, 2024 by Linda Lou Burton

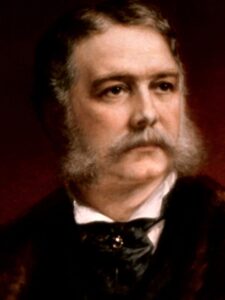

#21. Arthur, Chester Alan

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – Chester Alan Arthur (October 5, 1829 – November 18, 1886) was the 21st president of the United States, from 1881 to 1885, coming into office upon the death of President James Garfield. There is something sadly endearing about this man, if you look carefully. I’d always pictured Chester, known as “Elegant Arthur” and “Gentlemen Boss,” as a rather portly man who came up through political appointment. But once he assumed the office of President, he followed an honorable path, to the surprise of reformers. He advocated and enforced the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act, something Hayes had worked towards and Garfield pioneered – the awarding of federal jobs based on merit, and not the spoils system. He overcame a negative reputation and left the presidency “more generally respected, alike by political friend and foe.” Mark Twain said of Chester “No duty was neglected in his administration.”

Endearing? Consider his feelings about his wife Nell, who died before he became president. Chester deeply mourned the loss of Nell, and ordered fresh flowers placed daily before her portrait in the White House. He could see St John’s Episcopal Church from the Oval Office, so commissioned a Tiffany stained glass window dedicated to his wife installed in the church, specifying that it be lighted so he could view it at night. Chester never remarried, and was quite protective of his children – son Alan was at Princeton during the White House years, and daughter Ellen, who was 9 at the beginning, was sheltered from the public eye. Chester is credited with saying “I may be president of the United States, but my private life is nobody’s damned business.” Just days before he died, he burned all his personal and official papers. Would I invite this man to my party? Well, yes, I think I would, though I doubt such a private person would come.

Endearing? Consider his feelings about his wife Nell, who died before he became president. Chester deeply mourned the loss of Nell, and ordered fresh flowers placed daily before her portrait in the White House. He could see St John’s Episcopal Church from the Oval Office, so commissioned a Tiffany stained glass window dedicated to his wife installed in the church, specifying that it be lighted so he could view it at night. Chester never remarried, and was quite protective of his children – son Alan was at Princeton during the White House years, and daughter Ellen, who was 9 at the beginning, was sheltered from the public eye. Chester is credited with saying “I may be president of the United States, but my private life is nobody’s damned business.” Just days before he died, he burned all his personal and official papers. Would I invite this man to my party? Well, yes, I think I would, though I doubt such a private person would come.

How It All Began

Chester’s father William was born in Ireland, graduated from college in Belfast, and emigrated to Canada where he began teaching school near the Vermont border. He married schoolteacher Malvina Stone in 1821 and together they had nine children – Chester was the fifth-born. William studied law for a bit, but eventually became a Freewill Baptist minister. He was also a staunch abolitionist, frequently at odds with his congregation, so the family moved a lot, living in a number of towns in Vermont before eventually settling in Schenectady, New York. Despite the frequent school changes, Chester did well, and in 1845 enrolled at Schenectady’s Union College, following the traditional classical curriculum. In his senior year he was president of the debate society, and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa; during breaks, he taught school. From the time of his graduation in 1848 he taught school and studied law, eventually moving to New York city. He was admitted to the New York bar in 1854 and joined the firm of Erastus Culver, an abolitionist lawyer and family friend. Can you see where this is going?

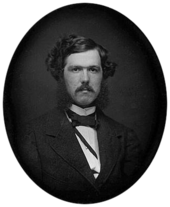

In one of his first cases as lead attorney, Chester represented Elizabeth Jennings Graham after she was denied a seat on a streetcar because she was black. He won the case and the verdict led to the desegregation of New York city’s streetcar lines. An auspicious beginning! In 1856 Chester started a new law partnership with friend Henry Gardiner; the two traveled to Kansas to set up a practice there. At the time, Kansas was undergoing a brutal struggle between pro and anti-slavery forces. The two New Yorkers didn’t like “frontier life” however and after four months came back to New York. In 1859 Chester really “settled down” – he married Ellen (Nell) Herndon; he was 30, she was 22. Chester had grown up in rural Vermont, remember. But Nell’s family was

In one of his first cases as lead attorney, Chester represented Elizabeth Jennings Graham after she was denied a seat on a streetcar because she was black. He won the case and the verdict led to the desegregation of New York city’s streetcar lines. An auspicious beginning! In 1856 Chester started a new law partnership with friend Henry Gardiner; the two traveled to Kansas to set up a practice there. At the time, Kansas was undergoing a brutal struggle between pro and anti-slavery forces. The two New Yorkers didn’t like “frontier life” however and after four months came back to New York. In 1859 Chester really “settled down” – he married Ellen (Nell) Herndon; he was 30, she was 22. Chester had grown up in rural Vermont, remember. But Nell’s family was  socially prominent – she was friends with the Vanderbilts, Astors, and Roosevelts. Her social network widened Chester’s political contacts and her mother’s wealth allowed Chester and Nell luxuries such as a Tiffany-furnished three-story brownstone townhouse on Lexington Avenue. Chester devoted himself to the New York Republican party, rising through political patronage to the position of Adjutant General of New York, with a US Army rank of brigadier general. Nell was a talented soprano who sang with the Mendelssohn Glee Club and performed at benefits around New York. They had three children together, and what appeared to be a strong marriage.

socially prominent – she was friends with the Vanderbilts, Astors, and Roosevelts. Her social network widened Chester’s political contacts and her mother’s wealth allowed Chester and Nell luxuries such as a Tiffany-furnished three-story brownstone townhouse on Lexington Avenue. Chester devoted himself to the New York Republican party, rising through political patronage to the position of Adjutant General of New York, with a US Army rank of brigadier general. Nell was a talented soprano who sang with the Mendelssohn Glee Club and performed at benefits around New York. They had three children together, and what appeared to be a strong marriage.

The Unexpected Deaths

Chester and Nell lost their firstborn son in 1863; he died of convulsions at age two and a half, a devastating event. On January 10, 1880, Nell Arthur came down with a cold. She quickly developed pneumonia and died two days later at age 42; another unexpected and devastating event. Chester was 50 by then; son Alan was 16 and daughter Ellen 9. Chester was elected Vice President of the United States that November, on the ticket with James Garfield as President; they were sworn in on March 4, 1881. And then, yet another unexpected death; James Garfield was shot on July 2, 1881 and lingered until September 19.

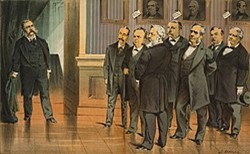

Chester was in New York when he learned that James Garfield had been shot. No one was sure who, if anyone, could exercise presidential authority. Chester was reluctant to be seen acting as president while the president still lived; there were conspiracy theories due to the fact that Garfield’s assassin loudly proclaimed “Arthur is president now!” Chester refused to travel to Washington and was at his home on Lexington Avenue in New York on September 19 when he learned that Garfield had died. Just after midnight Chester dispatched messengers to locate a judge who could administer the presidential oath. At 2:15 am on September 20 John Brady, a Justice of the New York Supreme Court, administered the oath of office in Chester’s home.

Next Actions

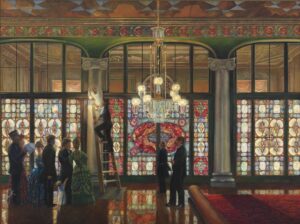

Chester prepared and mailed to the White House a proclamation calling for a special Senate session, ensuring that the Senate had legal authority to convene even if he died before reaching Washington. He then joined the funeral train as Garfield’s body was moved from New Jersey to Washington. On September 22 he re-took the oath of office before Chief Justice Morrison Waite to ensure procedural compliance; former presidents Ulysses Grant and Rutherford Hayes were present for the ceremony in the capitol. Chester took up residence at the home of Senator John Jones shortly afterwards and ordered remodeling of the White House, to include a 50-foot glass Tiffany screen.

Chester prepared and mailed to the White House a proclamation calling for a special Senate session, ensuring that the Senate had legal authority to convene even if he died before reaching Washington. He then joined the funeral train as Garfield’s body was moved from New Jersey to Washington. On September 22 he re-took the oath of office before Chief Justice Morrison Waite to ensure procedural compliance; former presidents Ulysses Grant and Rutherford Hayes were present for the ceremony in the capitol. Chester took up residence at the home of Senator John Jones shortly afterwards and ordered remodeling of the White House, to include a 50-foot glass Tiffany screen.

Chester’s youngest sister Mary served as White House hostess during his time in office, and helped to care for the children. But sadly, Chester was diagnosed with Bright’s disease, an acute inflammation of the kidneys, shortly after becoming president. As Mark Twain noted, no duty was neglected on Chester’s watch, but due to his poor health he retired at the end of his term. He left the White House in March 1885 and returned to his home in New York City where he died November 18, 1886. His New York private funeral was attended by President Cleveland and former President Hayes; he is buried beside his wife in Albany Rural Cemetery in Menands, New York.

What Remains

Son Chester Alan Arthur II graduated Princeton and Columbia Law School but warned by Chester on his deathbed to “avoid politics,” Alan spent his life playing polo and traveling. He died in 1937. Daughter Ellen Arthur, who was only 15 when her father died, stayed out of politics as well; she died in 1915 at the age of 44.

Son Chester Alan Arthur II graduated Princeton and Columbia Law School but warned by Chester on his deathbed to “avoid politics,” Alan spent his life playing polo and traveling. He died in 1937. Daughter Ellen Arthur, who was only 15 when her father died, stayed out of politics as well; she died in 1915 at the age of 44.

The elegant Tiffany-filled Lexington Avenue brownstone that was the Arthur home for so many years today houses Kalustyan’s, a Mediterranean grocery store, on the first two floors, and apartments on the top three. It is the only surviving building in New York City where a president was sworn into office. The Tiffany screen Chester put into the White House entrance hall was removed in 1902 by President Teddy Roosevelt, who didn’t care for Victorian style; it was auctioned off and eventually installed in the Belvedere Hotel in Maryland, which burned to the ground in 1923.

The Presidential Succession Act of 1886 provided that in case of the removal, death, resignation or inability of both the President and Vice President, a cabinet officer “appointed by and with consent of the Senate and eligible to the office of president and not under impeachment” would act as President until the disability of the President or Vice-President is removed or a President shall be elected. This last provision replaced the 1792 provision for a double-vacancy special election, a loophole left for Congress to call such an election if that course seemed appropriate.