» January 10th, 2025

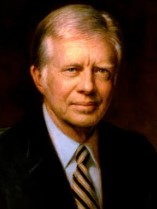

Jimmy Carter: He Did It!

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas January 10, 2025 – In my post of July 23, 2024, I stated that Jimmy Carter was “the best-loved ‘after-president’ we’ve ever had.” And the proof of that continues. Everybody was pulling for Jimmy to reach his 100th birthday on October 1. And he did it! Although Jimmy had been in home hospice care since February of last year, birthday greetings came from every direction, with a star-studded bash in Atlanta and a parade in Plains in his honor.

But Jimmy had an even bigger goal than going down in history as the only president to reach 100. He wanted to vote for Vice President Kamala Harris for President in the November 5, 2024 election. And he did it! He sent his early ballot on October 16, with the guarantee that his vote would count even if he died before November 5.

But Jimmy had an even bigger goal than going down in history as the only president to reach 100. He wanted to vote for Vice President Kamala Harris for President in the November 5, 2024 election. And he did it! He sent his early ballot on October 16, with the guarantee that his vote would count even if he died before November 5.

Jimmy died December 29.

It was fitting, I think, that Kamala presented the eulogy at the service held in the Capitol Rotunda on January 8, 2025. Here are a few of her words:

We have heard much today and in recent days about President Carter’s impact in the four decades after he left the White House. Rightly so. Jimmy Carter established a new model for what it means to be a former president and leaves an extraordinary post-presidential legacy, from founding the Carter Center, which has helped advance global human rights and alleviate human suffering, to his public health work in Latin America and Africa, to his tireless advocacy for peace and democracy.

Throughout his life and career, Jimmy Carter retained a fundamental decency and humility. James Earl Carter Jr loved our country. He lived his faith, he served the people, and he left the world better than he found it. And in the end, Jimmy Carter’s works speak for him, louder than any tribute we can offer. May his life be a lesson for the ages and a beacon for the future.

Throughout his life and career, Jimmy Carter retained a fundamental decency and humility. James Earl Carter Jr loved our country. He lived his faith, he served the people, and he left the world better than he found it. And in the end, Jimmy Carter’s works speak for him, louder than any tribute we can offer. May his life be a lesson for the ages and a beacon for the future.

January 9, 2025

Another packed service was held at the National Cathedral in DC at 10 AM on January 9. President Joe Biden delivered the eulogy there; former presidents Bill Clinton, George Bush, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump were on row two; former vice presidents Al Gore and Mike Pence behind them. Hillary Clinton, Laura Bush, Melania Trump were there too; somber dark suits on a day to leave political differences behind for a bit.

Burial took place in Plains, Georgia in the late afternoon. Yes, he is buried beside Rosalynn, by a willow tree in the yard of the only home they ever owned.

Just as the motorcade arrived at the residence, the US Navy conducted a “Missing Man Formation” flyover, which means a single aircraft breaks away from the formation and soars skyward, symbolizing the departure of a life from the ranks.

Just as the motorcade arrived at the residence, the US Navy conducted a “Missing Man Formation” flyover, which means a single aircraft breaks away from the formation and soars skyward, symbolizing the departure of a life from the ranks.

“Today, Naval Aviators from Strike Fighter Wing Atlantic were honored to salute President Carter with a 21-plane flyover over his home in Plains, Georgia,” said Rear Adm. Doug Verissimo, commander, Naval Air Force Atlantic. “On behalf of the men and women of Naval Air Forces, we are grateful to commemorate the legacy of a leader who lived his life in service to our nation.”

And He Did It!

Wrapping it up, I chose a photo of Jimmy exiting a polling site in October 2005 in Monrovia, Liberia. Jimmy was 81 at the time, and he was out there monitoring an election. It’s just one of those things he did! He and Rosalyn founded the Carter Center in 1982; monitoring elections around the world to promote fair and free voting was just one thing on their agenda.

Wrapping it up, I chose a photo of Jimmy exiting a polling site in October 2005 in Monrovia, Liberia. Jimmy was 81 at the time, and he was out there monitoring an election. It’s just one of those things he did! He and Rosalyn founded the Carter Center in 1982; monitoring elections around the world to promote fair and free voting was just one thing on their agenda.

Read more about the Carter’s work; visit these sites. The Jimmy Carter Library and Museum was opened in 1986. The following year, buildings connected to Carter’s life were granted status as National Historic Sites and in 2021 were collectively renamed the Jimmy Carter National Historic Park.

Jimmy Carter Library https://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/

Carter National Historic Site https://www.nps.gov/jica/index.htm

I picked out a few more of his “awards and honors” too:

- Carterpuri, a village in Haryana, India, was renamed in his honor after he visited in 1978.

- In 1998, the U.S. Navy named the third and final Seawolf-class submarine USS Jimmy Carter, honoring Carter and his service as a submarine officer.

- Carter received the United Nations Prize in the Field of Human Rights, given in honor of human rights achievements, and the Hoover Medal, recognizing engineers who have contributed to global causes.

- Carter received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2002 “for his decades of untiring effort to find peaceful solutions to international conflicts, to advance democracy and human rights, and to promote economic and social development.”

And look at this one:

- In November 2024, Carter received his 10th nomination for the Grammy Award for Best Spoken Word Album for audio recordings of his books. He has won three times—for Our Endangered Values: America’s Moral Crisis (2007), A Full Life: Reflections at 90 (2016), and Faith: A Journey For All (2018).

The man just never quit.

» August 23rd, 2024

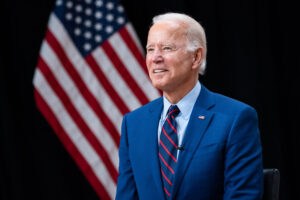

#46. Biden, Joseph Robinette Jr

Updated from Original Post of January 22, 2021 from Little Rock, Arkansas by Linda Lou Burton — Joseph Robinette Biden Jr (b 1942) is the 46th president of the United States.

Updated from Original Post of January 22, 2021 from Little Rock, Arkansas by Linda Lou Burton — Joseph Robinette Biden Jr (b 1942) is the 46th president of the United States.

My Thoughts January 22, 2021

Besides what you’ve heard from media blasts, what do you know about the man? Probably what the latest media focus tells you, and which media you choose to listen to. To start with a basic fact, let’s take Joe’s birthdate. It is November 20, 1942, so yes, he’s the oldest elected president ever. Is that a bad thing? Maybe that depends on your age. Do you have respect for your elders? Or do you lean towards the theory that people “lose it” as they age? I was three years old when Joe was born, so in my mind, Joe hasn’t lost it, he “gets it.” He, and I, have  lived through the scares and fears and patriotism of WWII and its aftermath; the conformity of the 50s when folks settled back into traditional roles, though civil rights issues began to grip our thinking. The 60s, 70s, 80s brought us Barbie, Vietnam, Moonwalks; women’s rights, gay rights, Watergate; hippies, me-first, greed, AIDS. We morphed into the 90s learning to depend on the internet, chatting with total strangers once the whine and click of “signing on” connected us to the world beyond. We got mail! We eased into a new century despite doomsday forecasts of our worldly systems shutting down. We got hooked on technology and upping our range; our phones became cameras; Bluetooth, Facebook, YouTube became our crutch; Twitter and Going Viral became the norm.

lived through the scares and fears and patriotism of WWII and its aftermath; the conformity of the 50s when folks settled back into traditional roles, though civil rights issues began to grip our thinking. The 60s, 70s, 80s brought us Barbie, Vietnam, Moonwalks; women’s rights, gay rights, Watergate; hippies, me-first, greed, AIDS. We morphed into the 90s learning to depend on the internet, chatting with total strangers once the whine and click of “signing on” connected us to the world beyond. We got mail! We eased into a new century despite doomsday forecasts of our worldly systems shutting down. We got hooked on technology and upping our range; our phones became cameras; Bluetooth, Facebook, YouTube became our crutch; Twitter and Going Viral became the norm.

Then came 2020, “the worst year ever” is its label now; it slapped us hard. A virus? As the year wore on, our disbelief turned into shrieks of blame; or avoidance of the issue. We quarantined at home, or we did not. We masked our faces, or we did not. We were angry, disillusioned, unemployed, sad. We canceled plans, and dreams. Buried feelings festered as we sat at home, losing sight of what had been our normal life. Small irritations grew large. We missed the human touch. When you can’t be in the world yourself, you reach for promises, hoping somebody knows what to do.

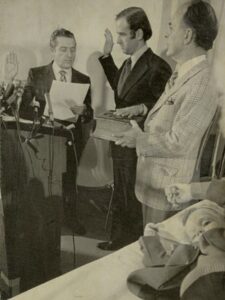

That is the world as Joe Biden steps into the role of leadership in 2021. What a plate of hoo-ha we’ve handed him to deal with! Can we trust him to do it? Joe is not perfect. But he has lived through vastly changing times, as humans have behaved badly, and then regretted it; as thinking has changed with lessons learned. Joe has done some really good things in his lifetime; and apologized for a lot of things he regrets. Joe has experienced great loss; he was sworn into his first role as a Senator in 1973 in the hospital, just after his wife and infant daughter died in a tragic accident that injured his young sons. He has been a single parent, but moved on into a second marriage with Jill Jacobs, now in its 44th year. He has fathered four children – Beau,

That is the world as Joe Biden steps into the role of leadership in 2021. What a plate of hoo-ha we’ve handed him to deal with! Can we trust him to do it? Joe is not perfect. But he has lived through vastly changing times, as humans have behaved badly, and then regretted it; as thinking has changed with lessons learned. Joe has done some really good things in his lifetime; and apologized for a lot of things he regrets. Joe has experienced great loss; he was sworn into his first role as a Senator in 1973 in the hospital, just after his wife and infant daughter died in a tragic accident that injured his young sons. He has been a single parent, but moved on into a second marriage with Jill Jacobs, now in its 44th year. He has fathered four children – Beau,  Hunter, Naomi, Ashley – and has seven grandchildren today. He has a sister and two brothers, Valerie, Jim, and Frank. His parents – Joseph Sr and Catherine Eugenia Finnegan Biden – lived long, into their 80s and 90s; they died in 2002 and 2010; his oldest son Beau had too short a life; he died in 2015 at the age of 46. Various members of his family have made him proud, and at times given reason for concern, but he’s always been a family man, and a man of faith. Records show that Joe lived a basically middle-class life; his parents dealt with both good times and hard times. Joe had to overcome a speech impediment; his college years were not extraordinary. But Joe persevered. Joe gets it.

Hunter, Naomi, Ashley – and has seven grandchildren today. He has a sister and two brothers, Valerie, Jim, and Frank. His parents – Joseph Sr and Catherine Eugenia Finnegan Biden – lived long, into their 80s and 90s; they died in 2002 and 2010; his oldest son Beau had too short a life; he died in 2015 at the age of 46. Various members of his family have made him proud, and at times given reason for concern, but he’s always been a family man, and a man of faith. Records show that Joe lived a basically middle-class life; his parents dealt with both good times and hard times. Joe had to overcome a speech impediment; his college years were not extraordinary. But Joe persevered. Joe gets it.

A lot of people like Joe Biden. Let’s look at his elective record, since 1970, when he was 28 years old, just starting out there in Delaware:

- 1970 County Councilor, 10,573 votes or 55% of total

- 1972 US Senator, 116,006 votes or 50% of total

- 1978 US Senator, 93,930 votes or 58% of total

- 1984 US Senator, 147,831 votes or 60% of total

- 1990 US Senator, 112,918 votes or 63% of total

- 1996 US Senator, 165,465 votes or 60% of total

- 2002 US Senator, 135,235 votes or 58% of total

- 2008 US Senator, 257,484 votes or 53% of total

- 2008 US Vice President, 69,498,516 votes or 53% of total

- 2012 US Vice President, 69,915,795 votes or 51% of total

- 2020 US President, 81,268,757 votes or 51% of total

That adds up to 217,722,528 times people “voted for Joe” in the last 50 years. And 81,268,757 people who want Joe to be our President for the next four years. If you are one of them, or if you are not, you need to read what he said in his Inaugural Address on January 20, as he accepted the job we elected him to do; all 2,514 words of it. It’s a declaration of intent, filled with purpose, and closing with a sacred oath. It’s a request to each of us to do our part; a leader is there to lead, to enable us to be the best that we can be. A great America is a cooperative effort. Wear your mask. Get your vaccination. Help your neighbor. Listen before you leap. See the possibilities.

That adds up to 217,722,528 times people “voted for Joe” in the last 50 years. And 81,268,757 people who want Joe to be our President for the next four years. If you are one of them, or if you are not, you need to read what he said in his Inaugural Address on January 20, as he accepted the job we elected him to do; all 2,514 words of it. It’s a declaration of intent, filled with purpose, and closing with a sacred oath. It’s a request to each of us to do our part; a leader is there to lead, to enable us to be the best that we can be. A great America is a cooperative effort. Wear your mask. Get your vaccination. Help your neighbor. Listen before you leap. See the possibilities.

I share with you a few lines of that Inaugural Address that were most meaningful to me.

Recent weeks and months have taught us a painful lesson. There is truth and there are lies. Lies told for power and for profit. And each of us has a duty and responsibility, as citizens, as Americans, and especially as leaders – leaders who have pledged to honor our Constitution and protect our nation — to defend the truth and to defeat the lies.

I understand that many Americans view the future with some fear and trepidation. I understand they worry about their jobs, about taking care of their families, about what comes next. I get it. But the answer is not to turn inward, to retreat into competing factions, distrusting those who don’t look like you do, or worship the way you do, or don’t get their news from the same sources you do.

We must end this uncivil war that pits red against blue, rural versus urban, conservative versus liberal.

We can do this if we open our souls instead of hardening our hearts. If we show a little tolerance and humility. If we’re willing to stand in the other person’s shoes just for a moment. Because here is the thing about life: There is no accounting for what fate will deal you.

There are some days when we need a hand. There are other days when we’re called on to lend one. That is how we must be with one another. And, if we are this way, our country will be stronger, more prosperous, more ready for the future….in the work ahead of us, we will need each other.

My fellow Americans, I close today where I began, with a sacred oath. Before God and all of you I give you my word.

- I will always level with you.

- I will defend the Constitution.

- I will defend our democracy.

- I will defend America.

- I will give my all in your service thinking not of power, but of possibilities.

My Thoughts August 23, 2024

That’s what Joe had to say back in 2021. He considered running for a second term, but on July 21, 2024 endorsed Vice President Kamala Harris for this essential leadership role as our 47th President of the United States. The Democratic Party held its convention in Chicago in August and nominated Kamala Harris; she selected Minnesota Governor Tim Walz as her running mate and on August 22 gave her acceptance speech, asking that we move forward, past the divisive battles of the past, not as one party or faction, but together as Americans.

Think about what those fellows intended back in 1788 when they were trying to get a country going. We were just 4 million people back then, and we didn’t have insta-hate available at our fingertips. Today we are 337 million people (and 1 more added every 28 seconds). What a mess we can make of things! OR NOT. It is essential that we play nice on the playground.

My grandson understood that when he was four years old. We’d gone to the playground, where he headed straight for the slide. A little guy, maybe two years old, kept breaking in line. Matthew watched this for about three turns as the child pushed and kicked anyone in his way; he watched the reactions of the other kids; he watched the child’s mother standing at the sidelines, saying nothing. Then, to my surprise, Matthew approached the mother, and quietly said “Maam, your son’s behavior on the playground is unacceptable. May I show him how to make friends?” The mother stared at him a moment, but nodded “Go ahead.”

Matthew approached the little boy and said “Hey bud, let’s stand together.” The boy took Matthew’s outstretched hand and they approached the ladder, talking as they waited their turn. At the top the little fellow seated himself in Matthew’s lap, then squealing, happy, down the slide and back around, high fives with everyone in line.

If a four year old can make that much difference in his tiny bit of the world, surely the rest of us can.

» July 29th, 2024

#45. Trump, Donald John

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – Donald John Trump (b 1946) was the 45th President of the United States from 2017 to 2021. A media personality and businessman, he is the only president without prior military or government experience. And who was favored by 2.9 million fewer voters than the “other guy” (who, in fact, was a female). Nobody expected such a thing to happen, “ it just couldn’t” said all the polls. But it did. Donald Trump received 304 electoral votes, Hillary Clinton 227, and that’s what makes the win. Glued to our TVs as election returns came in state by state the evening of November 8, we watched it happen. The Associated Press called Pennsylvania for Trump at 1:35 AM EST, putting him at 267 electoral votes (270 needed to win). By 2:01, they had called both Maine and Nebraska’s second congressional districts for Trump, putting him at 269 electoral votes. At 2:29 the Associated Press called the election for Trump, with 279 electoral votes. By 2:37 Hillary Clinton had called Donald Trump and conceded the election. He gave his victory speech at 2:50 AM EST November 9, 2016.

Later that day, Hillary Clinton asked her supporters to accept the result. “Last night, I congratulated Donald Trump and offered to work with him on behalf of our country,” she said. “I hope he will be a successful president for all Americans. This is not the outcome we wanted or worked so hard for, and I’m sorry we did not win this election, but I feel pride and gratitude for this wonderful campaign we built together. This vast, diverse, creative, unruly and energized campaign. You represent the best of America, and being your candidate has been one of the greatest honors of my life.” Fighting back tears at times, she acknowledged the crowd’s disappointment, saying she — “and tens of millions of Americans” — felt it, too. “This is painful, and it will be for a long time. We have seen that our nation is more deeply divided than we thought. But I still believe in America, and I always will.”

Later that day, Hillary Clinton asked her supporters to accept the result. “Last night, I congratulated Donald Trump and offered to work with him on behalf of our country,” she said. “I hope he will be a successful president for all Americans. This is not the outcome we wanted or worked so hard for, and I’m sorry we did not win this election, but I feel pride and gratitude for this wonderful campaign we built together. This vast, diverse, creative, unruly and energized campaign. You represent the best of America, and being your candidate has been one of the greatest honors of my life.” Fighting back tears at times, she acknowledged the crowd’s disappointment, saying she — “and tens of millions of Americans” — felt it, too. “This is painful, and it will be for a long time. We have seen that our nation is more deeply divided than we thought. But I still believe in America, and I always will.”

Hillary Rodham Clinton (b 1946), was the first female presidential nominee of a major political party, and one of five in 58 elections over 229 years where the popular vote winner was defeated by electoral votes, meaning, simply, that the majority of voters did not get the person they chose. Hillary did not lose due to lack of experience; as a member of President Obama’s cabinet Hillary served as US Secretary of State; she was an elected US Senator from New York, was First Lady of the United States during President Clinton’s eight years and First Lady of Arkansas during the five terms her husband was governor. She majored in political science; earned a law degree at Yale; worked in numerous campaigns for over 40 years. She understood politics. Why did she lose this election? Part of the answer is her identification with the Old School; were voters just itching for a change?

Or was it simply personality differences? Hillary acknowledged once that “I’m not a natural politician, in case you haven’t noticed.” Did “charisma” just slap the dickens out of quieter manners? And how did the bolder louder candidate function in the presidential role? The next four years were brash, surprising, unsettling. Rated today in the bottom three of the “worst presidents ever” Donald Trump was defeated in the 2020 election and, in a shock wave front porch stand during the 2021 transition, almost wouldn’t leave. For the first time since the US Constitution was ratified in 1788, “peaceful transition of power” was in jeopardy. So what is the back story? Who is this Donald Trump?

Or was it simply personality differences? Hillary acknowledged once that “I’m not a natural politician, in case you haven’t noticed.” Did “charisma” just slap the dickens out of quieter manners? And how did the bolder louder candidate function in the presidential role? The next four years were brash, surprising, unsettling. Rated today in the bottom three of the “worst presidents ever” Donald Trump was defeated in the 2020 election and, in a shock wave front porch stand during the 2021 transition, almost wouldn’t leave. For the first time since the US Constitution was ratified in 1788, “peaceful transition of power” was in jeopardy. So what is the back story? Who is this Donald Trump?

The Gold

Let me tell you a story. Some 23 million immigrants came to the United States from Europe between the 1880s and the early 1920s. Add up the wars, misrule, conflicts, food shortages, swelling populations, and shrinking opportunities and you can see why such great numbers of Europeans left their homelands in search of something better. The largest group of immigrants were Germans from Europe’s Austro-Hungary Empire, and one of those was Friedrich Trump.

He was just 16, US immigration records show “Friedr. Trumpf” born in Kallstadt, Germany, immigrated via Bremen to the United States aboard the steamship Eider, departing on October 7 and arriving at the Castle Garden Emigrant Landing Depot in New York City October 19, 1885. Friedrich’s sister was already there; he settled in with her and began work as a barber, carefully saving his money. In 1891, when Washington became a state, he headed cross country to Seattle where he bought a restaurant at 208 Washington Street in Pioneer Square, the “action spot” of a frontier town. He fixed it up with new tables and chairs and named it The Dairy; he sold food and liquor and Rooms For Ladies. And he made money.

He was just 16, US immigration records show “Friedr. Trumpf” born in Kallstadt, Germany, immigrated via Bremen to the United States aboard the steamship Eider, departing on October 7 and arriving at the Castle Garden Emigrant Landing Depot in New York City October 19, 1885. Friedrich’s sister was already there; he settled in with her and began work as a barber, carefully saving his money. In 1891, when Washington became a state, he headed cross country to Seattle where he bought a restaurant at 208 Washington Street in Pioneer Square, the “action spot” of a frontier town. He fixed it up with new tables and chairs and named it The Dairy; he sold food and liquor and Rooms For Ladies. And he made money.

Two years later he sold The Dairy and moved north of Seattle to a new hotbed for gold mining, building a new restaurant to serve the miners. The Monte Cristo “gold bubble” burst, but by 1897 the Klondike Gold Rush had begun; he funded two miners who staked a claim; in 1898 he headed for the Yukon himself. And he opened another restaurant – this one along the trail at White Horse Pass, a trail so treacherous the horses often would be beat to death trying to  make the climb. (His menu included “fresh slaughtered horse.”) More money made; he moved again to Bennett, BC and opened The Artic Restaurant and Hotel, a two-story building among a sea of tents. The restaurant had one of the largest steel ranges in the area, offering fresh fruit and ptarmigan in addition to horse meat, it served over 3,000 meals a day. The hotel offered scales for measuring gold dust, gambling, private beds, and ladies, 24 hours a day. Until 1901, when the local government announced the suppression of prostitution, gambling, and liquor. Friedrich sold his shares, left the Yukon, and returned to Kallstadt, Germany at the age of 32 a wealthy man.

make the climb. (His menu included “fresh slaughtered horse.”) More money made; he moved again to Bennett, BC and opened The Artic Restaurant and Hotel, a two-story building among a sea of tents. The restaurant had one of the largest steel ranges in the area, offering fresh fruit and ptarmigan in addition to horse meat, it served over 3,000 meals a day. The hotel offered scales for measuring gold dust, gambling, private beds, and ladies, 24 hours a day. Until 1901, when the local government announced the suppression of prostitution, gambling, and liquor. Friedrich sold his shares, left the Yukon, and returned to Kallstadt, Germany at the age of 32 a wealthy man.

He met and soon proposed to Elisabeth Christ, they married in 1902 and moved to New York; a daughter was born in 1904. But Elisabeth was homesick, so back to Kallstadt. And a major slap. The Department of Interior announced an investigation to banish Friedrich from Germany! He had violated the “Resolution of the Royal Ministry of the Interior number 9916,” a law that punished immigration to North America to avoid military service with the loss of Bavarian and thus German citizenship. In February 1905, a royal decree was issued ordering Friedrich Trump to leave within eight weeks. He petitioned the ruling, but was unsuccessful. Friedrich and Elisabeth and daughter left for New York June 30, 1905.

The Business

Son Friedrich Christ Trump – Fred – was born October 24, 1905 in the Bronx, New York. And then another son, John, in 1907. Friedrich bought real estate on Jamaica Avenue, moving the family into the building and renting out rooms; he managed a hotel; he kept buying land. One day while on a walk with son Fred, he became extremely sick; the next day he was dead. His real estate holdings included a 2-story 7-room house in Queens, 5 vacant lots, $4,000 in savings, $3,600 in stocks, and 14 mortgages, placing his net worth at about $35,000 ($780,000 in 2024). The year was 1918; Fred was 13 years old. Elisabeth and Fred continued the real estate projects under the name Elisabeth Trump & Son. Fred grew up, married, and had five children. One of them was Donald Trump.

Son Friedrich Christ Trump – Fred – was born October 24, 1905 in the Bronx, New York. And then another son, John, in 1907. Friedrich bought real estate on Jamaica Avenue, moving the family into the building and renting out rooms; he managed a hotel; he kept buying land. One day while on a walk with son Fred, he became extremely sick; the next day he was dead. His real estate holdings included a 2-story 7-room house in Queens, 5 vacant lots, $4,000 in savings, $3,600 in stocks, and 14 mortgages, placing his net worth at about $35,000 ($780,000 in 2024). The year was 1918; Fred was 13 years old. Elisabeth and Fred continued the real estate projects under the name Elisabeth Trump & Son. Fred grew up, married, and had five children. One of them was Donald Trump.

Donald John Trump was born June 14, 1946 at Jamaica Hospital in Queens, New York, the fourth of the five children of Fred and Mary MacLeod Trump: Maryanne, Fred Jr, Elisabeth, Donald, and Robert. Father Fred was unforgivingly strict; the Legend of Grandfather framed everything he taught his children. Make a lot of money, however you can. Hold it tight and make some more; hardship looms. Donald grew up in Queens; he attended private schools, and in 1968 when he graduated from the University of Pennsylvania with a BS in economics he joined the family business. Father Fred stressed to Donald the art of deal-making. The rule: “Be a Killer.” The attitude: “Be A King.” When older brother Fred Jr declined leadership responsibility it came to Donald, passing into his hands in 1971 when he was 25.

The Trump Organization, through its various constituent companies and partnerships, has or has had interests in real estate development, investing, brokerage, sales and marketing, and property management. Trump Organization entities own, operate, invest in, and develop residential real estate, hotels, resorts, residential towers, and golf courses in various countries. They also operate or have operated in construction, hospitality, casinos, entertainment, book and magazine publishing, broadcast media, model management, financial services, food and beverages, business education, online travel, commercial and private aviation, and beauty pageants. Retail operations include or have included fashion apparel, jewelry and accessories, books, home furnishings, lighting products, bath textiles and accessories, bedding, home fragrance products, small leather goods, vodka, wine, barware, steaks, chocolate bars, and bottled spring water. No clear accounting of the value of these entities is available. Donald and his businesses have been plaintiffs or defendants in more than 4,000 legal actions.

The Finger

Did you watch The Apprentice? It ran from 2004-2015 with Donald as host, representing a successful businessman with a luxurious lifestyle. Opening theme was For the Love of Money, an R&B song by the O’Jays. The premise of the show was to conduct a job talent search for a person to head one of the Trump companies, offering the winner a one-year contract with a starting annual salary of $250,000. “Trumponomics” entered our lingo –a managerial concept meaning “impressing the boss is the only way to climb the corporate ladder.” The show is most remembered for its catchphrase “You’re fired!” shouted by a finger-pointing Donald.

Did you watch The Apprentice? It ran from 2004-2015 with Donald as host, representing a successful businessman with a luxurious lifestyle. Opening theme was For the Love of Money, an R&B song by the O’Jays. The premise of the show was to conduct a job talent search for a person to head one of the Trump companies, offering the winner a one-year contract with a starting annual salary of $250,000. “Trumponomics” entered our lingo –a managerial concept meaning “impressing the boss is the only way to climb the corporate ladder.” The show is most remembered for its catchphrase “You’re fired!” shouted by a finger-pointing Donald.

On June 29, 2015, NBC announced that the network was cutting ties with Donald Trump over the Republican presidential candidate’s statements about Mexican immigrants. “Due to the recent derogatory statements by Donald Trump regarding immigrants, NBC Universal is ending its business relationship with Mr Trump.” Donald was fired for comments he made about immigrants. Well then. A bit ironic? Besides Grandpa Friedrich from Germany,  Donald’s mother Mary Anne MacLeod immigrated from Scotland (naturalized 1942), his first wife Ivana Zelníčková immigrated from Czechoslovakia (naturalized 1988); his third wife Melanija Knavs immigrated from Slovenia (naturalized 2006). All with English as a second language; all seeking a better life in a land of opportunity, just like those Mexicans (who he continues to label as rapists and thieves trying to take our jobs). So there’s that.

Donald’s mother Mary Anne MacLeod immigrated from Scotland (naturalized 1942), his first wife Ivana Zelníčková immigrated from Czechoslovakia (naturalized 1988); his third wife Melanija Knavs immigrated from Slovenia (naturalized 2006). All with English as a second language; all seeking a better life in a land of opportunity, just like those Mexicans (who he continues to label as rapists and thieves trying to take our jobs). So there’s that.

The Twitter Finger

Fast forward to January 6, 2021. Donald was reaching the end of four years in the White House. And he’d been fired again. The 2020 presidential election saw the highest voter turnout by percentage since 1900. The Biden-Harris ticket received 306 electoral votes; the Trump-Pence 232. Everything was clear. Except to Donald. From early in the morning on November 4, 2020 with vote counts still going on in many states, Donald claimed he had won.  He ordered government agencies not to cooperate with the Biden transition team. On December 2, he posted a 46-minute video to his social media in which he repeated claims that the election was “rigged” and called for state legislatures or courts to overturn the election and allow him to stay in office. In a December 18 meeting in the White House a suggestion to overturn the election by invoking martial law and rerunning it under military supervision was discussed. Army Secretary Ryan McCarthy and Army Chief of Staff General James McConville issued a joint statement saying “There is no role for the US military in determining the outcome of an American election.”

He ordered government agencies not to cooperate with the Biden transition team. On December 2, he posted a 46-minute video to his social media in which he repeated claims that the election was “rigged” and called for state legislatures or courts to overturn the election and allow him to stay in office. In a December 18 meeting in the White House a suggestion to overturn the election by invoking martial law and rerunning it under military supervision was discussed. Army Secretary Ryan McCarthy and Army Chief of Staff General James McConville issued a joint statement saying “There is no role for the US military in determining the outcome of an American election.”

The 117th US Congress was scheduled to count and certify the Electoral College votes on January 6, 2021; vice president Mike Pence was to preside over the session. In December,  Donald called for his supporters to stage a massive protest in Washington on January 6 to argue against this certification using tweets such as “Big protest in DC on January 6th. Be there, will be wild!” By January, he began to pressure his vice-president to use his position to overturn election results and declare a Trump-Pence win. Mike Pence demurred; the law did not give him that power.

Donald called for his supporters to stage a massive protest in Washington on January 6 to argue against this certification using tweets such as “Big protest in DC on January 6th. Be there, will be wild!” By January, he began to pressure his vice-president to use his position to overturn election results and declare a Trump-Pence win. Mike Pence demurred; the law did not give him that power.

At noon on January 6, Donald made an hour-long televised speech at a rally on the Ellipse, with the White House as background, continuing to press claims that the election was fraudulent. The assembled crowd became a mob that stormed the US capitol, interrupting the Joint session of the US Congress where the Electoral College ballots were being certified, forcing lawmakers to flee for their lives.

We watched it happen, remember? The capitol was ransacked, five people died, damage to the building caused by attackers exceeded $2.7 million. But the process of law took place despite the worst of terrors; Congress reconvened that same night, soon after the Capitol was cleared of trespassers. Leaders of both parties, including Vice President Mike Pence, House  Speaker Nancy Pelosi, and Senate Speaker Mitch McConnell urged the legislators to confirm the electors. The Senate resumed its session around 8 pm and completed its work shortly before 4 am on Thursday, January 7, declaring Biden and Harris the winners 306–232. Vice President Pence affirmed the election result, formally declaring Biden the winner. Donald Trump did not attend the inauguration of

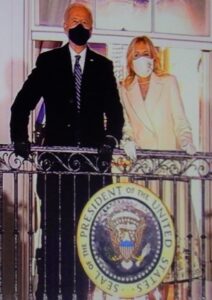

Speaker Nancy Pelosi, and Senate Speaker Mitch McConnell urged the legislators to confirm the electors. The Senate resumed its session around 8 pm and completed its work shortly before 4 am on Thursday, January 7, declaring Biden and Harris the winners 306–232. Vice President Pence affirmed the election result, formally declaring Biden the winner. Donald Trump did not attend the inauguration of  President Joe Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris on January 20, 2021. Mike Pence did.

President Joe Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris on January 20, 2021. Mike Pence did.

In February 2021 Donald Trump was impeached. The Senate voted 57–43 to convict him of inciting insurrection, but fell 10 votes short of the two-thirds majority required by the Constitution, and he was therefore acquitted. Other charges of efforts to overturn the election that led to the attack on the capitol, of election tampering, of willful retention of national defense information and classified documents, of hush money and business fraud, still hang over his head, tangled and delayed, waiting.

On May 21, 2024 Donald Trump was convicted by a New York jury of 34 charges in a scheme to illegally influence the 2016 election through a hush money payment to a porn actor who said the two had sex. (And this is a man who’s had three wives, five children and ten grandchildren, ah.)

The Insanity

On July 15, 2024, Donald Trump was nominated for the third time as a Republican presidential candidate at the National Convention in Milwaukee. He selected Senator JD Vance as his running mate.

Stay tuned. He’s been fired, but keeps applying. Here’s what I’m thinking – before any of you decide to rehire the man, review the job requirements. They’re simple; they don’t specify male or female, and they don’t specify skin color. It doesn’t matter who your grandpa was, or where you started out in life. But in order to BE president, a real honest-to-goodness worth-our-time president, a person must be over 35, a US citizen who lives here, and must, absolutely MUST “faithfully preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States.”

That’s the job. And frankly, I’d prefer someone who isn’t angry all the time. Just saying.

» July 28th, 2024

#44. Obama, Barack

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – Barack Hussein Obama II (b 1961) was the 44th President of the United States from 2009-2017. He goes into the history books as “ the first African-American president in US history,” self-identifying as African-American because his father was Kenyan, and his mother was born in Kansas. Father Barack Sr was a member of the Luo ethnic group that lived along the shores of Lake Victoria; at the time of his birth in 1934 Kenya was a protectorate of the British Empire. Mother Ann Dunham was an only child; when she was born in Wichita in 1942, her Dad was in the US Army; the family’s ancestry was mostly English, with a bit of Scottish, Welsh, and Irish mixed in. How in the world – our big old world – did two such disparate people come together, we all wondered, when we first began to hear of Barack. The story is remarkable, a story bigger than imagination. And equally remarkable is the story of the 2008 presidential election, when not only the first African-American sought a spot on a presidential ticket; it was also the year the first female sought that unique responsibility.

A History Lesson before we begin – in case you didn’t get the gist back in school. The US Constitution, ratified in 1789, was put together by white male landed gentry as an outline for governing 13 colonies that had bonded together in statehood as a democracy, free from the restrictions of a monarchy. The “right to vote,” that is, to select those who would contribute to the governing of those states, was left to the individual states. The qualifications for becoming president were age (35+), citizenship (not clearly defined), and residency (at least 14 years in the colonies-now-states).

A History Lesson before we begin – in case you didn’t get the gist back in school. The US Constitution, ratified in 1789, was put together by white male landed gentry as an outline for governing 13 colonies that had bonded together in statehood as a democracy, free from the restrictions of a monarchy. The “right to vote,” that is, to select those who would contribute to the governing of those states, was left to the individual states. The qualifications for becoming president were age (35+), citizenship (not clearly defined), and residency (at least 14 years in the colonies-now-states).

The first count of people was the 1790 US Census, which divided the population of almost 4 million into four categories, measuring Free White Males (over 16 and under 16), Free White Females, and Slaves. Free White Males made up 42% of the entire population; Free White Females 40%; Slaves 18%. The Constitution provided for a system of checks and balances – that is, self-correcting mechanisms – as a democracy should. To date it has been amended 27 times, the last in 1992. Let’s look at two that focused on voting rights:

- In 1868, during the presidency of #17 Andrew Johnson, the 14th Amendment to the Constitution was ratified, granting citizenship to all persons born or naturalized in the United States, including formerly enslaved people, and providing all citizens with “equal protection under the laws” (which did not assure them of voting privileges in every state).

- In 1920, during the presidency of #28 Woodrow Wilson, the 19th Amendment to the Constitution was ratified by the required 36 states, removing sex as a determinate for voting eligibility, stating “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex” (which still did not assure them of voting privileges in every state).

Since that first election in 1789, privileges and opportunities for “voting eligibility” improved but still varied state to state, as the disenfranchised protested, lobbied, and fought for change. But even getting “on the ticket” to be voted FOR was an exclusive white male accomplishment until 2008.

Since that first election in 1789, privileges and opportunities for “voting eligibility” improved but still varied state to state, as the disenfranchised protested, lobbied, and fought for change. But even getting “on the ticket” to be voted FOR was an exclusive white male accomplishment until 2008.

Now let’s be clear – the Constitution didn’t block that from happening; it was our own perception of suitability. We didn’t favor Catholics (give the Pope power?) or Jews or agnostics or atheists; we wanted Christians, no matter how fallen. We didn’t want a president who was too young or too old. Even though we prided ourselves on our diversity, we didn’t trust anyone with an African, or Asian, or Latino connection. No off-white colors, or accents. Women were “too emotional” to make good decisions, and heaven forbid anyone who was divorced, or gay.

The major deciding factor? Our individual comfort zones. Would we accept a person of color? A person of the right color but the wrong sex? Would we elect someone based simply on their skills and experience and character and charisma?

History Lesson over now, let’s look at the story of the first person who broke the color barrier.

It Started In Hawaii

Barack Hussein Obama II was born August 4, 1961, at Kapiolani Medical Center for Women and Children in Honolulu, Hawaii. His mother Stanley Ann Dunham (1942-1995) was 18, she’d entered the University of Hawaii fall semester, 1960. His father Barack Hussein Obama Sr (1934-1982) a 27-year-old foreign exchange student, was there on scholarship from Kenya. Ann and Barack wound up in the same class that fall.

Barack Hussein Obama II was born August 4, 1961, at Kapiolani Medical Center for Women and Children in Honolulu, Hawaii. His mother Stanley Ann Dunham (1942-1995) was 18, she’d entered the University of Hawaii fall semester, 1960. His father Barack Hussein Obama Sr (1934-1982) a 27-year-old foreign exchange student, was there on scholarship from Kenya. Ann and Barack wound up in the same class that fall.

Ann Dunham was born in Kansas; her family moved to California, then Washington; they lived in the Seattle area during her high school years. Dad Stanley Dunham was a salesman, Mom Madelyn worked at a bank; they wanted their daughter to attend Mercer Island High, a forward thinking school in an exclusive community. She graduated in 1960, high-spirited and ready for the U of Washington, but Dad sought business opportunities in Hawaii and insisted she move with them. She enrolled at the U of Hawaii that fall, met Barack, got pregnant, dropped out of school, and had a baby. In fall 1961 she moved back to Seattle with her infant  son, and spent the first year of his life as a student at U of Washington. The Department of Anthropology there created the Stanley Ann Dunham Scholarship Fund in 2015 to honor her, and her work, for Ann went on to receive a PhD in Anthropology; her career led her to Indonesia and years of work addressing women’s roles and rural poverty. And her infant son went on to become president of the United States.

son, and spent the first year of his life as a student at U of Washington. The Department of Anthropology there created the Stanley Ann Dunham Scholarship Fund in 2015 to honor her, and her work, for Ann went on to receive a PhD in Anthropology; her career led her to Indonesia and years of work addressing women’s roles and rural poverty. And her infant son went on to become president of the United States.

Barack Obama Sr was never a part of his son’s life; they met only once. He finished his last year at the U of Hawaii while Ann and baby were in Seattle; in 1962 he headed for Harvard. He was back in Kenya by 1964, and died there at the age of 48, leaving behind a trail of unrealized opportunities. He didn’t maintain a stable family life (though his relationships with four women produced eight children); he didn’t make best use of his fully funded scholarships (Harvard kicked him out of his PhD program); and he ultimately botched a prime job in Kenya. Barack published these words about his father’s absence in his life: I only remember my father for one month in my whole life, when I was 10….I think (his absence) contributed to me really wanting to be a good dad….because not having him there made me say to myself, “I want to make sure my girls feel like they’ve got somebody they can rely on.”

A Good Dad’s Childhood

Barack struck a home run in the “good dad” department. This 2015 photo by the cherry trees is typical of Obama family photos – smiles from Malia, Michelle, Barack, Sasha. The girls are even prettier nowadays; Barack is grayer, but that glow remains the same; something about the four of them seems upbeat, positive, unafraid; with maybe a little mischief lurking. Maybe? Strict about honoring responsibilities, Mom and Dad have taken these girls absolutely everywhere; they’ve seen the world. Michelle is one of the most sought-after public speakers and most admired First Ladies ever. And besides being a good Dad, and good husband, in October of his first year as president Barack was awarded a Nobel Peace Prize for “extraordinary efforts to strengthen international diplomacy and cooperation between peoples.”

Barack struck a home run in the “good dad” department. This 2015 photo by the cherry trees is typical of Obama family photos – smiles from Malia, Michelle, Barack, Sasha. The girls are even prettier nowadays; Barack is grayer, but that glow remains the same; something about the four of them seems upbeat, positive, unafraid; with maybe a little mischief lurking. Maybe? Strict about honoring responsibilities, Mom and Dad have taken these girls absolutely everywhere; they’ve seen the world. Michelle is one of the most sought-after public speakers and most admired First Ladies ever. And besides being a good Dad, and good husband, in October of his first year as president Barack was awarded a Nobel Peace Prize for “extraordinary efforts to strengthen international diplomacy and cooperation between peoples.”

You need a map to follow Barack’s childhood; the places he lived; the people who made up his larger family; the languages and cultures he experienced. No wonder international diplomacy was a positive trait. Go back to his first year of life – born in Honolulu, whisked to Seattle as the son of a college student; her skin white, his black. Mom Ann moved them back to Honolulu and resumed classes at the University of Hawaii in January 1963. And there she met Lolo Soetoro from Indonesia; he was studying geography at the University. They married in 1965; when Lolo’s visa expired he returned to Indonesia. Ann and Barack moved in with her parents, and Barack attended kindergarten at Noelani Elementary in Honolulu. Ann earned her BA in Anthropology in August 1967. On to Indonesia.

You need a map to follow Barack’s childhood; the places he lived; the people who made up his larger family; the languages and cultures he experienced. No wonder international diplomacy was a positive trait. Go back to his first year of life – born in Honolulu, whisked to Seattle as the son of a college student; her skin white, his black. Mom Ann moved them back to Honolulu and resumed classes at the University of Hawaii in January 1963. And there she met Lolo Soetoro from Indonesia; he was studying geography at the University. They married in 1965; when Lolo’s visa expired he returned to Indonesia. Ann and Barack moved in with her parents, and Barack attended kindergarten at Noelani Elementary in Honolulu. Ann earned her BA in Anthropology in August 1967. On to Indonesia.

Ann moved with Barack to Jakarta. Lolo worked on a topographic survey for the government; Ann taught English and served as Asst Director of the Indonesia-America Friendship Institute. Barack attended the Indonesian language Catholic school around the corner from their house for grades up to 3; then to Indonesian-language Besuki School through 4th grade. He picked up the Indonesian language, joined the Scouts, and everybody called him Barry. In the summer of 1970 Barry visited Grandpa and Grandma Dunham in Hawaii. And that August, his half-sister Maya Soetoro was born in Indonesia.

Ann moved with Barack to Jakarta. Lolo worked on a topographic survey for the government; Ann taught English and served as Asst Director of the Indonesia-America Friendship Institute. Barack attended the Indonesian language Catholic school around the corner from their house for grades up to 3; then to Indonesian-language Besuki School through 4th grade. He picked up the Indonesian language, joined the Scouts, and everybody called him Barry. In the summer of 1970 Barry visited Grandpa and Grandma Dunham in Hawaii. And that August, his half-sister Maya Soetoro was born in Indonesia.

Barack (Barry) started 5th grade at the top-rated private Punahou School in Honolulu, living with his grandparents. In 1972 Mom Ann moved back to Honolulu to start graduate study in anthropology at the U of Hawaii; from grades 6-8 Barack lived with his mother and Maya. Ann received her MA in Anthropology in 1974; she and Maya returned to Indonesia. Barack  chose to stay with his grandparents and continued his studies at Punahou School until graduation in 1979.

chose to stay with his grandparents and continued his studies at Punahou School until graduation in 1979.

In his memoir Barack describes his experiences growing up in his mother’s middle class family. His knowledge about his African father came mainly through family stories and photographs. Of his early childhood, he writes: “That my father looked nothing like the people around me—that he was black as pitch, my mother white as milk—barely registered in my mind.” Reflecting later on his formative years in Honolulu, he wrote: “The opportunity that Hawaii offered—to experience a variety of cultures in a climate of mutual respect—became an integral part of my world view, and a basis for the values that I hold most dear.”

Barack was still being called “Barry” by most folks when he arrived at Occidental College in Los Angeles in 1979. “He always went by Barry, for simplicity and as an accommodation to Anglo society,” a friend relayed later, “but I said I would only call him Barack, because it was a strong African name.” From LA to NY, Barack transferred to Columbia for his junior and senior years, earning a BA in political science; he worked a bit in New York, then Chicago; then entered Harvard Law School where he graduated magna cum laude in 1991. And in 1992, at the age of 31, he married Michelle.

Barack was still being called “Barry” by most folks when he arrived at Occidental College in Los Angeles in 1979. “He always went by Barry, for simplicity and as an accommodation to Anglo society,” a friend relayed later, “but I said I would only call him Barack, because it was a strong African name.” From LA to NY, Barack transferred to Columbia for his junior and senior years, earning a BA in political science; he worked a bit in New York, then Chicago; then entered Harvard Law School where he graduated magna cum laude in 1991. And in 1992, at the age of 31, he married Michelle.

The Good Husband Part

Michelle LaVaughn Robinson was born January 17, 1964, in Chicago, Illinois, the second child of Fraser and Marian Shields Robinson; her older brother was Craig. They lived in an apartment in Chicago’s South Shore community; life was described as “conventional” – Dad worked, Mom was home, dinner was around the table, school just down the street. Until 6th grade, when she entered gifted classes; she took advanced placement classes in high school, graduating in 1981. She followed her brother to Princeton, graduating cum laude in 1985; then on to Harvard Law School, graduating in 1988. She went to work at the law firm of Sidley Austin in Chicago, and that’s where she met one of the few African-Americans working there, Barack Obama. Story goes, they shared a business lunch. Barack has said it was an “opposites attract” scenario – she’d grown up in the stability of a two-parent home while his  childhood was “adventurous.” Barack had made a 1987 visit to Kenya in search of his African roots; though his father had died by then, he met a grandmother, a half-sister, and many cousins; his knowledge of “family” had widened considerably.

childhood was “adventurous.” Barack had made a 1987 visit to Kenya in search of his African roots; though his father had died by then, he met a grandmother, a half-sister, and many cousins; his knowledge of “family” had widened considerably.

And it continued to expand. On October 3, 1992 Barack and Michelle got married, gaining both of them a slew of in-laws. Their wedding took place at Trinity Church in Chicago; two of the bridesmaids were Barack’s half-sisters, Maya Soetoro from Indonesia and Auma Obama from Kenya, an international affair. But very traditional too; white roses, beautiful wedding gown, and all the reception-after fun.

The Obama Family Homes

After the honeymoon, Barack and Michelle lived in Chicago; he taught at the U of Chicago Law School, she became executive director for the Chicago Office of Public Allies. Barack was elected to the State Senate in 1996; Michelle became associate dean of student services at the U of Chicago. Daughter Malia was born in 1998, daughter Sasha in 2001. Barack was elected to the US Senate in 2004, and next thing you know, it was 2008.

How does it feel to know that 69,456,897 people chose you? January 20, 2009 was a glorious inauguration day; it set a record attendance for any event ever held in the city; add TV and the  Internet and it was one of the most-observed events ever by a global audience. Not too many noticed the word Chief Justice Roberts misplaced as he administered the oath of office (a do-over the next day just in case; it’s “faithfully execute” and not “execute faithfully” the duties of the president); the skies were clear for the parade and in the evening there were 10 inaugural balls.

Internet and it was one of the most-observed events ever by a global audience. Not too many noticed the word Chief Justice Roberts misplaced as he administered the oath of office (a do-over the next day just in case; it’s “faithfully execute” and not “execute faithfully” the duties of the president); the skies were clear for the parade and in the evening there were 10 inaugural balls.

It was so good, Barack did it again four years later. 65,915,796 voters wanted him back, even though everything didn’t get accomplished that we all wanted done (it never does). But he stayed the course.

I won’t rehash the legislation, new problems, old grudges, and great successes of Barack’s eight years in office; you lived through those times yourself. When the Obamas left the White House January 20, 2017, Barack and Michelle were in their 50’s, the girls moving fast through their teens. Their list of “firsts” forever marks the history books. What broader changes lie ahead? Are our Founding Fathers watching from the past, checking every now and then to see if we’ve caught the things they didn’t even think about, and made them right?

As to my party – Michelle and Barack are such good writers (so many books, so little time) I’d invite them over for a whole evening of story-telling. And maybe let them critique this post. I’d take notes.

» July 27th, 2024

#43. Bush, George Walker

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – George Walker Bush (b 1946) was the 43rd President of the United States from 2001-2009. #43 George and #6 John Quincy Adams share a unique place in the history books – both had a father who served as president. And having “Dad” precede you in such a position of glory must have been a heck of a thing to live up to. But there’s another way of looking at it – from Dad’s point of view – how did their offspring carry on the banner entrusted to them? #41 George H W Bush lived through the eight years of his son’s presidency and beyond, as expectations and analysis continue; remember his comment about the “trials and tribulations of my sons”? And one of those tribulations began before #43 George was even declared president; and in a strange way involved two Bush sons.

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – George Walker Bush (b 1946) was the 43rd President of the United States from 2001-2009. #43 George and #6 John Quincy Adams share a unique place in the history books – both had a father who served as president. And having “Dad” precede you in such a position of glory must have been a heck of a thing to live up to. But there’s another way of looking at it – from Dad’s point of view – how did their offspring carry on the banner entrusted to them? #41 George H W Bush lived through the eight years of his son’s presidency and beyond, as expectations and analysis continue; remember his comment about the “trials and tribulations of my sons”? And one of those tribulations began before #43 George was even declared president; and in a strange way involved two Bush sons.

A new phrase entered the lingo of the American public and it had to do with a voter’s vote getting properly counted. Or not. Hanging Chads became a physics lesson. Technology had evolved into the “hole punch ballot” so votes could be machine counted. Punch a hole in a ballot and let the machine count the holes.

A new phrase entered the lingo of the American public and it had to do with a voter’s vote getting properly counted. Or not. Hanging Chads became a physics lesson. Technology had evolved into the “hole punch ballot” so votes could be machine counted. Punch a hole in a ballot and let the machine count the holes.  But, alas, if the “chad” – that is the excess tissue that had to be removed in order to have a hole to count — wasn’t fully removed, well, you had a “hanging chad” and the machine didn’t know what to do. And those “hanging chad ballots” happened in the state of Florida, and the Governor of Florida was Jeb Bush, the son of #41 George and the brother of candidate George.

But, alas, if the “chad” – that is the excess tissue that had to be removed in order to have a hole to count — wasn’t fully removed, well, you had a “hanging chad” and the machine didn’t know what to do. And those “hanging chad ballots” happened in the state of Florida, and the Governor of Florida was Jeb Bush, the son of #41 George and the brother of candidate George.

The US Supreme Court was involved before George finally got into the White House. Opponent Al Gore, who had served as Vice President for eight years, racked up 48.4% of the popular vote; George Bush received 47.9%. But the “electoral college” system we use gave Bush 271 electoral votes and Gore 266 (you must have 270 to win). And Florida’s 25 electoral votes were the “hanging chad recount” issue. Do the math. The tally in Florida was so close – a difference of 537 individual votes out of six million cast in Florida – that a recount was called for; then a second one as “chads” continued under scrutiny. The US Supreme Court ruled on December 9 to reverse a Florida Supreme Court decision for a third count. On December 13, 2000, Al Gore conceded the election. He strongly disagreed with the Court’s decision, but in his concession speech stated that, “for the sake of our unity as a people and  the strength of our democracy, I offer my concession.” On the morning of January 6, 2001, carrying out the duty of the outgoing vice president, Al Gore presided over the joint session of the US Congress where the electoral votes from every state are officially counted, and declared George W Bush duly elected with 271 electoral votes to his own 266. On January 20 George Walker Bush was sworn in as our 43rd president.

the strength of our democracy, I offer my concession.” On the morning of January 6, 2001, carrying out the duty of the outgoing vice president, Al Gore presided over the joint session of the US Congress where the electoral votes from every state are officially counted, and declared George W Bush duly elected with 271 electoral votes to his own 266. On January 20 George Walker Bush was sworn in as our 43rd president.

Back to 1946

George Walker Bush was born July 6, 1946 at Grace Hospital in New Haven, Connecticut, the first of the six children of George Herbert Walker and Barbara Pierce Bush – George, Robin, Jeb, Neil, Marvin, Dorothy. Starting life as a “Connecticut Yankee” since Dad was a student at Yale at the time, George was two years old when the family moved to Odessa, Texas and Dad became a “Texas oil man.” So George grew up a Texan – Texas heat and Texas oil wells; the family moved about; the siblings arrived. George lived with change; his sister Robin’s bout with leukemia and death; his mother’s depression; his father’s expanding business. He went to Sam Houston

George Walker Bush was born July 6, 1946 at Grace Hospital in New Haven, Connecticut, the first of the six children of George Herbert Walker and Barbara Pierce Bush – George, Robin, Jeb, Neil, Marvin, Dorothy. Starting life as a “Connecticut Yankee” since Dad was a student at Yale at the time, George was two years old when the family moved to Odessa, Texas and Dad became a “Texas oil man.” So George grew up a Texan – Texas heat and Texas oil wells; the family moved about; the siblings arrived. George lived with change; his sister Robin’s bout with leukemia and death; his mother’s depression; his father’s expanding business. He went to Sam Houston  Elementary and San Jacinto Junior High in Midland; by 1959 the family was in Houston and George was sent to Kinkaid, a college prep school there. For grades 10-12 he was sent cross country to Phillips Academy Andover in Massachusetts, and then Yale, as Dad had done; sports and fraternities too, but with an east coast difference from his familiars. He graduated Yale with a BA in history in 1968, a C student he said, but “good at rugby.”

Elementary and San Jacinto Junior High in Midland; by 1959 the family was in Houston and George was sent to Kinkaid, a college prep school there. For grades 10-12 he was sent cross country to Phillips Academy Andover in Massachusetts, and then Yale, as Dad had done; sports and fraternities too, but with an east coast difference from his familiars. He graduated Yale with a BA in history in 1968, a C student he said, but “good at rugby.”

The Context of Vietnam

US military troops were sent to Vietnam beginning in 1965; by 1969 more than 500,000 were stationed there. The last units left Vietnam March 29, 1973. The priority of call for the draft was based on the birthdates of registrants born between 1944-1950; those exempt were in university education or medically unfit. Thousands of young men evaded the draft by moving to Canada; thousands joined the ROTC or National Guard in order to avoid being sent to the controversial ground war in the jungles of Vietnam.

The Military and Harvard

Unmarried, out of college, and physically fit, George faced the same choices as his predecessor Bill Clinton faced in 1968 when he graduated from Georgetown – choices framed by the war in Vietnam. George joined the Texas Air National Guard with a commitment to serve until 1974. After two years of training, he was assigned to Houston, flying Convair F-102s with the 147th Reconnaissance Wing out of the Ellington Field Joint Reserve Base. His application to the U of Texas law school in 1970 was rejected; in December 1972 the last draft call was issued. George moved to Montgomery, Alabama to work on the US Senate campaign of Republican Winton Blount and was suspended from flying for failure to take a scheduled physical exam, but drilled with the Alabama Air National Guard. In 1973 he was accepted in a graduate program at Harvard. Honorably discharged from the Air Force Reserve in 1974, the next year he received his Harvard MBA.

Unmarried, out of college, and physically fit, George faced the same choices as his predecessor Bill Clinton faced in 1968 when he graduated from Georgetown – choices framed by the war in Vietnam. George joined the Texas Air National Guard with a commitment to serve until 1974. After two years of training, he was assigned to Houston, flying Convair F-102s with the 147th Reconnaissance Wing out of the Ellington Field Joint Reserve Base. His application to the U of Texas law school in 1970 was rejected; in December 1972 the last draft call was issued. George moved to Montgomery, Alabama to work on the US Senate campaign of Republican Winton Blount and was suspended from flying for failure to take a scheduled physical exam, but drilled with the Alabama Air National Guard. In 1973 he was accepted in a graduate program at Harvard. Honorably discharged from the Air Force Reserve in 1974, the next year he received his Harvard MBA.

Enter Laura

George was 31 in 1977 when he established a small oil exploration company; and that was the year he met, and married, a girl named Laura. Laura Welch was the only child of Harold and Jenna Welch, born November 4, 1946, in Midland, Texas. By the time she and George met she was already a school teacher there; with a BS in education from SMU (1968) and a master’s degree in library science from the U of Texas (1973). A pretty good match, it seems; the story goes that when George proposed to Laura, she accepted based on one thing: “that I’ll never have to give a campaign speech.” We know how that worked out; but as of this writing their marriage is in its 47th year and George continues to give Laura credit for “smoothing his rough edges.” And he gives her credit for helping him overcome his problem with alcohol. “I woke up with a hangover the morning after my 40th birthday celebration,” he said, “and decided it was time to quit.” He avers he hasn’t had a drink since 1986. Stories abound of his 20 years of alcohol abuse, of his bar-hopping and mediocre performance in the military and in school. And theories of how such abuse affects future decision making are out there; in particular the decisions he made during his eight years as president. But that’s getting ahead of the story; let’s follow what he did, and what was happening around him, in those 24 years between 1977-2001.

George was 31 in 1977 when he established a small oil exploration company; and that was the year he met, and married, a girl named Laura. Laura Welch was the only child of Harold and Jenna Welch, born November 4, 1946, in Midland, Texas. By the time she and George met she was already a school teacher there; with a BS in education from SMU (1968) and a master’s degree in library science from the U of Texas (1973). A pretty good match, it seems; the story goes that when George proposed to Laura, she accepted based on one thing: “that I’ll never have to give a campaign speech.” We know how that worked out; but as of this writing their marriage is in its 47th year and George continues to give Laura credit for “smoothing his rough edges.” And he gives her credit for helping him overcome his problem with alcohol. “I woke up with a hangover the morning after my 40th birthday celebration,” he said, “and decided it was time to quit.” He avers he hasn’t had a drink since 1986. Stories abound of his 20 years of alcohol abuse, of his bar-hopping and mediocre performance in the military and in school. And theories of how such abuse affects future decision making are out there; in particular the decisions he made during his eight years as president. But that’s getting ahead of the story; let’s follow what he did, and what was happening around him, in those 24 years between 1977-2001.

The Businesses, The Kids, And Stuff

- 1977 – George established Arbusto Energy, a small oil exploration company, name later changed to Bush Exploration. George and Laura were married November 5 in Midland, Texas.

- 1978 – George ran for US House of Representatives from Texas 19th district, lost.

- 1981 – George and Laura became parents with the birth of twins Barbara Pierce Bush and Jenna Welch Bush; George’s father became US Vice President.

- 1984 – George became chairman when his company merged with Spectrum 7. Decreased oil prices caused the company to fold into Harken Energy Corporation; George became a member of the Board of Directors. There was an insider trading investigation by SEC.

- 1985 – George’s father re-elected vice president.

- 1986 – George vowed to give up drinking.

- 1988 – George and family moved to Washington to work on his father’s presidential campaign.

- 1989 – George’s father elected US president. George arranged for a group of investors to purchase a controlling interest in MLB’s Texas Rangers for $89 million; invested $500,000 himself and became managing general partner; George actively led team projects and attended games for the next 5 years becoming publicly more visible.

- 1991 – George was one of seven people selected to run his father’s 1992 presidential campaign.

- 1993 – George’s father lost his second presidential bid; Bill Clinton was inaugurated. George considered a candidacy to become commissioner of baseball.

- 1994 – George declared his candidacy for the Texas gubernatorial election; brother Jeb was running for governor in Florida.

- 1995 – George elected governor of Texas, became focus of attention as a potential future presidential candidate. Brother Jeb defeated in his bid for Florida governor.

- 1997 – Bill Clinton re-elected president.

- 1998 – George re-elected governor of Texas with 69% of the vote, first Texas governor to be elected to two consecutive terms. George promoted faith-based organizations; decided to seek 2000 Republican presidential nomination; and sold his shares in Texas Rangers for over $15 million. Brother Jeb elected governor of Florida.

- 1999 – Bill Clinton impeached, but remained in office with a high approval rating.

A New Century Begins

As Texas Governor, George signed a bill into law proclaiming June 10, 2000 to be “Jesus Day” in Texas, urging people to “follow the example of Jesus” and answer the call to service helping those in need. On August 3, in acceptance of his nomination as presidential candidate at the Republican Convention in Philadelphia, George attacked the Clinton administration on defense and military topics, high taxes, and a lack of dignity and respect for the presidency. Headed towards November, George campaigned as a compassionate conservative, criticizing opponent Al Gore over gun control and taxation.

You know what happened next. That was the year chads became a household word. By the end of the next eight years the Federal Budget had gone from a surplus of $236 billion to a deficit of$459 billion. Did the lid fly off Pandora’s box?

The first catastrophe happened just 234 days into George’s presidency. On the morning of September 11, 2001, four Islamic terrorist suicide attacks struck the United States, killing 2,977 people. Two hijacked planes crashed into the Twin Towers in New York City; a third plane struck the Pentagon in Washington; the fourth plane, believed to be headed for the US capitol, crashed in a Pennsylvania field due to passenger heroism – they simply revolted against the hijackers, opting for their deaths there rather than the horrific consequences of having our capitol destroyed. The US went to war. On March 20, 2003 US forces invaded Iraq; on May 1 George Bush announced “mission accomplished.”

The first catastrophe happened just 234 days into George’s presidency. On the morning of September 11, 2001, four Islamic terrorist suicide attacks struck the United States, killing 2,977 people. Two hijacked planes crashed into the Twin Towers in New York City; a third plane struck the Pentagon in Washington; the fourth plane, believed to be headed for the US capitol, crashed in a Pennsylvania field due to passenger heroism – they simply revolted against the hijackers, opting for their deaths there rather than the horrific consequences of having our capitol destroyed. The US went to war. On March 20, 2003 US forces invaded Iraq; on May 1 George Bush announced “mission accomplished.”

In the 2004 presidential election George’s conduct during the war on terrorism was rewarded; he won 50.7 percent of the popular vote and defeated John Kerry with 286 electoral votes. But by 2005, George’s approval rating had dropped below 50 percent; people were angry that US troops were now entangled in an Iraqi civil war; and at home, Hurricane Katrina struck, and destroyed, the city of New Orleans and much of the Gulf Coast. George’s handling of Federal assistance to the thousands of homeless still brands him today as a “failed president.” And then, in 2007, as families had been madly borrowing against their home equity to “maintain lifestyle,” the housing bubble burst; the economy tanked. By 2008 election time, American voters were ready for the Democrats again.

The Afterlife

After welcoming Barack and Michelle Obama to the White House, and participating in their inauguration day, George and Laura returned to Texas; they’ve got a ranch in Crawford, and a home in Dallas. George and Laura remain friends with the Obamas; they’ve attended the Trump and the Biden inaugurations; they’ve stayed in touch. George has taken up painting as a hobby –self-portraits, world leaders, veterans; still life and dogs too; several books of his paintings have been published.

After welcoming Barack and Michelle Obama to the White House, and participating in their inauguration day, George and Laura returned to Texas; they’ve got a ranch in Crawford, and a home in Dallas. George and Laura remain friends with the Obamas; they’ve attended the Trump and the Biden inaugurations; they’ve stayed in touch. George has taken up painting as a hobby –self-portraits, world leaders, veterans; still life and dogs too; several books of his paintings have been published.  In 2019 on the 10th anniversary of South Korean president Roh Moo-hyun’s death, George presented a portrait of the man to his family. That was a nice gesture, don’t you think?

In 2019 on the 10th anniversary of South Korean president Roh Moo-hyun’s death, George presented a portrait of the man to his family. That was a nice gesture, don’t you think?

George’s parents died in 2018; but comparisons of father/son continue still, and that’s the touching thing. When you think of it, George was “expected to follow” in Dad’s footsteps; sent to the same schools and expected to desire the same success as a war hero and superior student. In truth he was more like his mother. Barbara never cared a flip about school; when she met George H W at the age of 16 she started planning her wedding, and her family, with no interest in college or career. She loved sports; she loved hanging out with a crowd; she wasn’t much for sticking by the rules. And the world admired that in our “National Grandmother.” So I say enough with the comparisons!