» posted on Tuesday, July 10th, 2012 by Linda Lou Burton

Marcus Whitman, Missionary Doctor

Linda Burton posting from Olympia, Washington – We saw a lot of faces today. Faces of capitol visitors like ourselves, and faces of history, in bronze statues and busts both inside and out, in renderings of the face of George Washington in the shining state seal and on banners furled from balconies, in portraits of former governors hanging on the wall of the Governors Office, and even on the magnificent Tiffany chandelier hanging in the rotunda. But at the end of the day one face and one story in particular stood out. We aimed for an on-the-hour tour – son Rick,

Linda Burton posting from Olympia, Washington – We saw a lot of faces today. Faces of capitol visitors like ourselves, and faces of history, in bronze statues and busts both inside and out, in renderings of the face of George Washington in the shining state seal and on banners furled from balconies, in portraits of former governors hanging on the wall of the Governors Office, and even on the magnificent Tiffany chandelier hanging in the rotunda. But at the end of the day one face and one story in particular stood out. We aimed for an on-the-hour tour – son Rick,  grandkids Andrew and Kayla, and me – and arrived just as a bus-load of Japanese students on a summer study program came in. We began clicking cameras at the same time; the Tour Volunteer manning the front desk stepped up to sort us out for Japanese or English-speaking guides. Above the fray I spotted a hale and hearty looking figure; a statue in bronze who appeared to be looking across the room and beyond. I walked over and read the name inscribed across the bottom: Marcus Whitman. His story is one of good intent, with a tragic ending. Listen.

grandkids Andrew and Kayla, and me – and arrived just as a bus-load of Japanese students on a summer study program came in. We began clicking cameras at the same time; the Tour Volunteer manning the front desk stepped up to sort us out for Japanese or English-speaking guides. Above the fray I spotted a hale and hearty looking figure; a statue in bronze who appeared to be looking across the room and beyond. I walked over and read the name inscribed across the bottom: Marcus Whitman. His story is one of good intent, with a tragic ending. Listen.

Marcus Whitman (1802-1847)

Marcus Whitman was a doctor and a missionary whose heart was set on ministering to the Indians of the northwest, and on helping white settlers as they migrated west. It was the clash of these separate elements that ultimately led to his death. Here’s his story.

Marcus Whitman was born in 1802 in Federal Hollow, New York to Alice and Beza Whitman; Beza died when Marcus was only seven and he was sent to live with an uncle in Massachusetts. Marcus wanted to become a minister, but there was no money for his schooling. As a young man he returned to New York and apprenticed with a physician, finally receiving a medical degree from Fairfield Medical College. He practiced for a few years in Canada, but “going west” was what he longed to do.

Marcus Whitman was born in 1802 in Federal Hollow, New York to Alice and Beza Whitman; Beza died when Marcus was only seven and he was sent to live with an uncle in Massachusetts. Marcus wanted to become a minister, but there was no money for his schooling. As a young man he returned to New York and apprenticed with a physician, finally receiving a medical degree from Fairfield Medical College. He practiced for a few years in Canada, but “going west” was what he longed to do.

In 1834 Marcus applied to the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions and eventually was accepted as a missionary doctor. In 1835 he traveled to present-day northwestern Montana and northern Idaho to minister to bands of Flathead and Nez Perce Indians; at the end of his assignment he promised the Nez Perce he would return with other missionaries and teachers and live with them.

Back in New York, two things happened. Marcus volunteered to go west again; and he got married. Narcissa Prentiss was eager to go west as a missionary, but as a single woman had not been allowed to do so. Narcissa was a teacher of physics and chemistry so she and Marcus made an extraordinary team; they married in 1836 and headed west, joining a caravan of fur traders in seven covered wagons. Henry and Eliza Spalding were other missionaries on the journey, led by mountain men Milton Sublette and Thomas Fitzpatrick. The group established several missions; Marcus and Narcissa settled in the territory of the Cayuse and Nez Perce tribes, a few miles west of present-day Walla Walla, Washington.

Back in New York, two things happened. Marcus volunteered to go west again; and he got married. Narcissa Prentiss was eager to go west as a missionary, but as a single woman had not been allowed to do so. Narcissa was a teacher of physics and chemistry so she and Marcus made an extraordinary team; they married in 1836 and headed west, joining a caravan of fur traders in seven covered wagons. Henry and Eliza Spalding were other missionaries on the journey, led by mountain men Milton Sublette and Thomas Fitzpatrick. The group established several missions; Marcus and Narcissa settled in the territory of the Cayuse and Nez Perce tribes, a few miles west of present-day Walla Walla, Washington.

Marcus farmed and provided medical care; Narcissa set up a school for the Indian children. Their daughter Alice Clarissa (1837-1839), named after her two grandmothers, was the first white child born in Oregon Country; sadly, she drowned at age two. After that the Whitmans took in eleven orphaned children, adopting eight from one family whose parents had died; they also established a boarding school for settlers’ children.

It was 1843, after a visit back east, when Marcus led a large group of wagon trains west, thus establishing the viability of the Oregon Trail that hundreds of thousands of emigrants would use over the next decade. As more and more white settlers arrived, they brought new infectious diseases to the Indian tribes. In 1847 a severe epidemic of measles struck, resulting in high death rates, especially among the children. Although Marcus and Narcissa cared for both Cayuse and white settlers, half the Cayuse died and nearly all their children died. Seeing that more whites survived, the Cayuse blamed the Whitmans for the devastation to their tribe. On November 29, 1847, Cayuse warriors destroyed the buildings of the settlement, captured 53 women and children, and massacred fourteen people, including Narcissa and Marcus Whitman.

It was 1843, after a visit back east, when Marcus led a large group of wagon trains west, thus establishing the viability of the Oregon Trail that hundreds of thousands of emigrants would use over the next decade. As more and more white settlers arrived, they brought new infectious diseases to the Indian tribes. In 1847 a severe epidemic of measles struck, resulting in high death rates, especially among the children. Although Marcus and Narcissa cared for both Cayuse and white settlers, half the Cayuse died and nearly all their children died. Seeing that more whites survived, the Cayuse blamed the Whitmans for the devastation to their tribe. On November 29, 1847, Cayuse warriors destroyed the buildings of the settlement, captured 53 women and children, and massacred fourteen people, including Narcissa and Marcus Whitman.

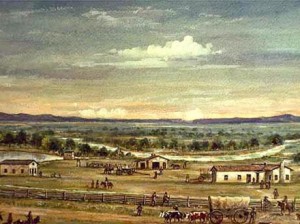

You can visit the Whitman Mission National Historic Site today, about seven miles west of Walla Walla, Washington. The National Park Service website offers this comment:

Retribution or Revenge? The 1847 Whitman “Massacre” horrified Americans and impacted the lives of the peoples of the Columbia Plateau for decades afterwards. Was killing the Whitmans justified legal retribution, an act of revenge, or some combination of both? The circumstances that surround this tragic event resonate with modern issues of cultural interaction and differing perspectives.

Retribution or Revenge? The 1847 Whitman “Massacre” horrified Americans and impacted the lives of the peoples of the Columbia Plateau for decades afterwards. Was killing the Whitmans justified legal retribution, an act of revenge, or some combination of both? The circumstances that surround this tragic event resonate with modern issues of cultural interaction and differing perspectives.

Whitman Mission National Historic Site includes the original mission site, a mass grave where Marcus and Narcissa Whitman are buried, the Whitman memorial shaft, and a Visitor Center with a small museum. The park is open all year, 7 days a week, except for Thanksgiving, Christmas Day and New Year’s Day. The grounds are open until dark; Visitor Center hours vary by season. The park is located in southeastern Washington, 7 miles west of Walla Walla off of Highway 12. National Park Service Whitman Mission site http://www.nps.gov/whmi/index.htm

Whitman College in Walla Walla, Whitman County, Washington is named in honor of Marcus Whitman; so is the Wallowa–Whitman National Forest, Mount Rainier’s Whitman Glacier, and numerous schools, including Marcus Whitman Central School in Rushville, New York. In 1953, the state of Washington donated a statue of Whitman by the sculptor Avard Fairbanks to the National Statuary Hall Collection in the United States Capitol and placed a copy in the Washington State Capitol grand foyer, where we saw it today. His demeanor appears to be rugged, but kind; is that a Bible he holds in one hand, and medical bags in the other?

Whitman College in Walla Walla, Whitman County, Washington is named in honor of Marcus Whitman; so is the Wallowa–Whitman National Forest, Mount Rainier’s Whitman Glacier, and numerous schools, including Marcus Whitman Central School in Rushville, New York. In 1953, the state of Washington donated a statue of Whitman by the sculptor Avard Fairbanks to the National Statuary Hall Collection in the United States Capitol and placed a copy in the Washington State Capitol grand foyer, where we saw it today. His demeanor appears to be rugged, but kind; is that a Bible he holds in one hand, and medical bags in the other?

Touring the Washington State Capitol http://www.ga.wa.gov/visitor/virtualtour/tour.html