» posted on Sunday, June 16th, 2024 by Linda Lou Burton

#2. Adams, John

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was the first vice-president of the United States and the first vice-president who then became president. He was the first president who FOUGHT to be president, and he even FATHERED a president. How did these presidential leanings begin? I’m going to give you three words; watch for them as the story continues. One is “prestige,” one is “Humphrey,” and one is “tea.” John was not a tall, slender, easy-with-people kind of guy. He was 5’7” with a round tummy and a Puritan heart. If you invited him to your party, he would not come; or if he did, he would not have danced. But he would have observed everything, and gone home and written notes about everyone there. He was a famous diarist, who paid attention to what was going on. He had strong feelings, and never failed to express them. He did not have a military career, but he was a fighter nonetheless. He was a WORD fighter. His big brain was bursting with ideas, opinions, and knowledge.

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was the first vice-president of the United States and the first vice-president who then became president. He was the first president who FOUGHT to be president, and he even FATHERED a president. How did these presidential leanings begin? I’m going to give you three words; watch for them as the story continues. One is “prestige,” one is “Humphrey,” and one is “tea.” John was not a tall, slender, easy-with-people kind of guy. He was 5’7” with a round tummy and a Puritan heart. If you invited him to your party, he would not come; or if he did, he would not have danced. But he would have observed everything, and gone home and written notes about everyone there. He was a famous diarist, who paid attention to what was going on. He had strong feelings, and never failed to express them. He did not have a military career, but he was a fighter nonetheless. He was a WORD fighter. His big brain was bursting with ideas, opinions, and knowledge.

Yes, John was well educated. He was even born in Braintree! (Now Quincy, Massachusetts.) John was the firstborn of John Sr and Susanna Boylston Adams; he was three when brother Peter came along and six when brother Elihu was born. They lived on the family farm; his father was a farmer, a cordwainer (shoemaker), a deacon in the Congregational Church, and a councilman who supervised the building of schools and roads. John’s formal education began when he was six – a school for boys and girls, conducted at a teacher’s home; the textbook was the New England Primer. Next he went to Braintree Latin School and studied Latin, Rhetoric, logic, and arithmetic. Maybe the teacher was dull – John skipped classes until his father commanded him to stay in school. “You shall comply with my desires,” was the word. John Sr took another action as well – he hired a new schoolmaster! It worked.

John entered Harvard at age sixteen and was a keen scholar; he studied the works of ancient writers such as Plato and Cicero in their original languages. He graduated in 1755 (age 20) with an A B degree and taught school for a while. His father expected him to become a minister, but John was more interested in “prestige” (note that word), and honor. He wrote to his father that he would become a lawyer, as he found among lawyers “noble and gallant achievements,” but among the clergy the “pretended sanctity of some absolute dunces.” So there!

John entered Harvard at age sixteen and was a keen scholar; he studied the works of ancient writers such as Plato and Cicero in their original languages. He graduated in 1755 (age 20) with an A B degree and taught school for a while. His father expected him to become a minister, but John was more interested in “prestige” (note that word), and honor. He wrote to his father that he would become a lawyer, as he found among lawyers “noble and gallant achievements,” but among the clergy the “pretended sanctity of some absolute dunces.” So there!

In 1758 John earned an A M from Harvard, and in 1759, at the age of 24, was admitted to the bar. His habit of writing in his diary about events and his impressions of people continued; he was inspired by James Otis Jr’s 1761 argument challenging the legality of British writs of assistance, which allowed the British to search a home without notice or reason. John observed the packed courtroom as Otis argued passionately for the colonists’ rights; later he said “Then and there the child independence was born.” In 1763, at the age of 28, John wrote seven essays for Boston newspapers under the name “Humphrey Ploughjogger,” (note the word Humphrey!). He ridiculed the “thirst for power” he perceived among the Massachusetts colonial elite. His influence began to emerge from his work as a constitutional lawyer and his analysis of history; but his bluntness was often a constraint in his career.

In 1758 John earned an A M from Harvard, and in 1759, at the age of 24, was admitted to the bar. His habit of writing in his diary about events and his impressions of people continued; he was inspired by James Otis Jr’s 1761 argument challenging the legality of British writs of assistance, which allowed the British to search a home without notice or reason. John observed the packed courtroom as Otis argued passionately for the colonists’ rights; later he said “Then and there the child independence was born.” In 1763, at the age of 28, John wrote seven essays for Boston newspapers under the name “Humphrey Ploughjogger,” (note the word Humphrey!). He ridiculed the “thirst for power” he perceived among the Massachusetts colonial elite. His influence began to emerge from his work as a constitutional lawyer and his analysis of history; but his bluntness was often a constraint in his career.

John got married though, to Abigail Smith, a third cousin. The wedding took place October 25, 1764 — he was 29, she was 20 – and though at first he had not been fond of Abigail and her sisters, they became close because they had two things in common – a love of books, and kindred personalities. John had inherited an 8-acre farm in 1761 when his father died; he and Abigail lived there until 1783; they had six children; four reached adulthood and one became president.

John got married though, to Abigail Smith, a third cousin. The wedding took place October 25, 1764 — he was 29, she was 20 – and though at first he had not been fond of Abigail and her sisters, they became close because they had two things in common – a love of books, and kindred personalities. John had inherited an 8-acre farm in 1761 when his father died; he and Abigail lived there until 1783; they had six children; four reached adulthood and one became president.

What was the third word I asked you to remember? It was “tea,” as in, The Boston Tea Party. Date: December 16, 1773. Action: The British schooner Dartmouth loaded with tea to be traded subject to the new Tea Act dropped anchor in Boston harbor. Demonstration: Protestors demolished 342 chests of tea; in today’s dollars worth about $1 million. The next day, John wrote to his friend James Warren about the audacious stroke:

“Last Night 3 Cargoes of Bohea Tea were emptied into the Sea. This Morning a Man of War sails. This is the most magnificent Movement of all. There is a Dignity, a Majesty, a Sublimity, in this last Effort of the Patriots, that I greatly admire. The People should never rise, without doing something to be remembered—something notable And striking. This Destruction of the Tea is so bold, so daring, so firm, intrepid and inflexible, and it must have so important Consequences, and so lasting, that I cant but consider it as an Epocha in History.”

The Boston Tea Party proved to be one of the many reactions that led to the American Revolutionary War; you know how that ended. As for John Adams’ blazing patriotism and activism, he became a principal leader of the Revolution. He assisted in drafting the Declaration of Independence in 1776 and was its foremost advocate in Congress. As a diplomat in Europe, he helped negotiate the peace treaty with Great Britain and secured vital governmental loans. He was the primary author of the Massachusetts Constitution in 1780, which influenced the United States’ own constitution, as did his earlier Thoughts on Government.

Here is his resume with regard to government positions:

- Member of Continental Congress, 1774-78

- Commissioner to France, 1778

- Minister to the Netherlands, 1780

- Minister to England, 1785

- Vice President, 1789-97

- President, 1797-1801

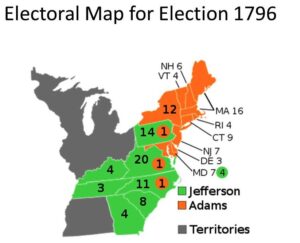

No candidates were put forth for voters to choose from in 1796; George Washington declined to be considered a third time; Thomas Jefferson was the clear Republican favorite and John Adams the Federalist frontrunner. The “campaign” was confined to newspaper attacks and political rallies; John declared he wanted to “stay out of the silly and wicked game of electioneering.” Considered by many as “too vain and arrogant” to follow the Federalist party line, in the end John Adams won by a narrow margin of 71 electoral votes to Thomas Jefferson’s 68. That meant, of course, that Jefferson was Adams vice-president, the only election in which a president and vice president were elected from opposing tickets.

No candidates were put forth for voters to choose from in 1796; George Washington declined to be considered a third time; Thomas Jefferson was the clear Republican favorite and John Adams the Federalist frontrunner. The “campaign” was confined to newspaper attacks and political rallies; John declared he wanted to “stay out of the silly and wicked game of electioneering.” Considered by many as “too vain and arrogant” to follow the Federalist party line, in the end John Adams won by a narrow margin of 71 electoral votes to Thomas Jefferson’s 68. That meant, of course, that Jefferson was Adams vice-president, the only election in which a president and vice president were elected from opposing tickets.

During his single term, John Adams encountered fierce criticism from the Jeffersonian Republicans and from rivals in his own Federalist Party, led by Alexander Hamilton. Even Jefferson was puzzled by Adams’ decision to retain Washington’s cabinet, noting that “the Hamiltonians who surround him are only a little less hostile to him than to me.” Adams maintained the economic programs of Hamilton, but was in most respects independent of his cabinet. Shortly after his inauguration, Hamilton sent him a detailed letter filled with policy suggestions for the new administration; Adams dismissively ignored it. Though Adams’ term was free of scandal, he spent most of his time at his home in Massachusetts; he preferred the quietness of domestic life and ignored the political patronage and office seekers which other office holders utilized.

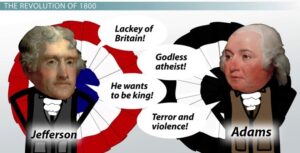

The 1800 presidential campaign got nasty. It was bitter, with malicious insults by partisan presses on both sides. Jefferson’s rumored affairs with slaves were used against him; but he was also portrayed as an apostle of liberty and man of the people; Adams was labelled a monarchist and accused of insanity and marital infidelity. Hamilton sent out a pamphlet strongly attacking Adams, which included personal insults, such as vilifying the president’s “disgusting egotism” and “ungovernable temper.” He concluded that Adams was “emotionally unstable, given to impulsive and irrational decision, unable to coexist with his advisers, and generally unfit to be president.”

The 1800 presidential campaign got nasty. It was bitter, with malicious insults by partisan presses on both sides. Jefferson’s rumored affairs with slaves were used against him; but he was also portrayed as an apostle of liberty and man of the people; Adams was labelled a monarchist and accused of insanity and marital infidelity. Hamilton sent out a pamphlet strongly attacking Adams, which included personal insults, such as vilifying the president’s “disgusting egotism” and “ungovernable temper.” He concluded that Adams was “emotionally unstable, given to impulsive and irrational decision, unable to coexist with his advisers, and generally unfit to be president.”

Karma did what Karma does – the pamphlet destroyed the Federalist Party and ended Hamilton’s political career.When the electoral votes were counted, Adams finished third with 65 votes; Jefferson and Burr tied for first with 73 votes each. Because of the tie, the election went to the House of Representatives, where each state had one vote and a super majority was required for victory. On February 17, 1801 – on the 36th ballot – Jefferson was elected by a vote of 10 to 4 (two states abstained). The complications arising out of the 1796 and 1800 elections prompted Congress and the states to refine the process whereby the Electoral College elects a president and a vice president through the 12th Amendment, which became a part of the Constitution in 1804.

John Adams departed the White House – he’d only lived there for five months – in the predawn hours of March 4, 1801, and did not attend Jefferson’s inauguration. Only three out-going presidents (having served a full term) have not attended their successors’ inaugurations – John Adams, John Quincy Adams, and Andrew Johnson.

During the first four years of retirement, John Adams made little effort to contact others. He generally stayed quiet on public matters and did not publicly denounce Jefferson’s actions as president. “We ought to Support every Administration as far as We can in Justice,” he said. Son John Quincy was elected to the Senate in 1803, and both men supported Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase. After Jefferson’s retirement from public life in 1809, Adams became more vocal; in early 1812 he and Jefferson reconciled. Their fourteen-year correspondence (158 letters) lasted the rest of their lives and is considered a great legacy of American literature. On July 4, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence, Adams died at his Massachusetts home at approximately 6:20 PM. His last words were “Thomas Jefferson survives,” unaware that Jefferson had died several hours before.

During the first four years of retirement, John Adams made little effort to contact others. He generally stayed quiet on public matters and did not publicly denounce Jefferson’s actions as president. “We ought to Support every Administration as far as We can in Justice,” he said. Son John Quincy was elected to the Senate in 1803, and both men supported Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase. After Jefferson’s retirement from public life in 1809, Adams became more vocal; in early 1812 he and Jefferson reconciled. Their fourteen-year correspondence (158 letters) lasted the rest of their lives and is considered a great legacy of American literature. On July 4, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence, Adams died at his Massachusetts home at approximately 6:20 PM. His last words were “Thomas Jefferson survives,” unaware that Jefferson had died several hours before.

His eldest son, John Quincy Adams, had been inaugurated as the he sixth president of the United States the previous year.

Tomorrow: #3. Thomas Jefferson