» June 21st, 2024

#7. Jackson, Andrew

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States (1829 to 1837), and a man of many contradictions. The first person to write his biography after his death, James Parton, summed it like this: “Andrew Jackson…was a patriot and a traitor. He was one of the greatest generals, and wholly ignorant of the art of war. A brilliant writer, elegant, eloquent, without being able to compose a correct sentence or spell words of four syllables. The first of statesmen, he never devised, he never framed, a measure. He was the most candid of men, and was capable of the most profound dissimulation. A most law-defying law-obeying citizen. A stickler for discipline, he never hesitated to disobey his superior. A democratic autocrat. An urbane savage. An atrocious saint.” Would you want this man at your party? I would; I’d like to hear what he thinks of the Electoral College system today. Some outcomes have even been worse than what happened to him back in 1824. But it might be a tricky evening – he shot a lot of people, and, he got shot, and shot AT, many times in his 78 years. When he died, he still had bullets rattling around in his chest. He had scars on his face and in his heart; and he had grudges going way, way back. But there are also stories of great passion, and tenderness.

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States (1829 to 1837), and a man of many contradictions. The first person to write his biography after his death, James Parton, summed it like this: “Andrew Jackson…was a patriot and a traitor. He was one of the greatest generals, and wholly ignorant of the art of war. A brilliant writer, elegant, eloquent, without being able to compose a correct sentence or spell words of four syllables. The first of statesmen, he never devised, he never framed, a measure. He was the most candid of men, and was capable of the most profound dissimulation. A most law-defying law-obeying citizen. A stickler for discipline, he never hesitated to disobey his superior. A democratic autocrat. An urbane savage. An atrocious saint.” Would you want this man at your party? I would; I’d like to hear what he thinks of the Electoral College system today. Some outcomes have even been worse than what happened to him back in 1824. But it might be a tricky evening – he shot a lot of people, and, he got shot, and shot AT, many times in his 78 years. When he died, he still had bullets rattling around in his chest. He had scars on his face and in his heart; and he had grudges going way, way back. But there are also stories of great passion, and tenderness.

What happened to Andrew in his early life? It pretty much sucked; a Charles Dickenson-Oliver Twist tear-jerker if you ask me. This red-headed blue-eyed Irishman was in defense mode from his first breath, just trying to survive.

Stage One

Andrew Jackson and Elizabeth Hutchinson immigrated from Ireland in 1765; they landed in Philadelphia and headed south through the Appalachian Mountains to a Scots-Irish community on the border between North and South Carolina. They brought two children with them, Hugh was two, Robert was a year old. Three weeks before Andrew was born in March of 1767, his father was killed in a logging accident. Elizabeth and her three little boys lived with relatives in the community for a while; the boys had some schooling from a nearby priest. Contradictions began early on – Andrew was a bully, but he also took weaker kids under his wing in kindness. Andrew was nine when the Revolutionary War began; his brother Hugh was  killed in battle in 1779. Elizabeth encouraged Robert and Andrew to attend local militia drills; they soon became couriers; but were captured by the British in April 1781 (Andrew was 14). They were not good POW’s – Andrew refused to clean an officer’s boots; the officer’s sword quickly slashed his face and hand; it left Andrew with scars and an intense hatred for the British. The story doesn’t get prettier; both boys contracted smallpox and almost starved in captivity. Elizabeth somehow managed to secure their release; the three began walking the 40 miles back home when a torrential downpour began. Two days after returning home, Robert was dead and Andrew terribly ill. After nursing Andrew back to health, Elizabeth volunteered to nurse American prisoners of war on board two British ships in the Charleston harbor, where there had been an outbreak of cholera. She died from the disease in November and is buried in an unmarked grave. By the end of 1781, Andrew was an orphan. Summary of his 14th year – he suffered captivity by the British, near starvation, the disease of smallpox, and the loss of two brothers and his mother. The scars from his smallpox and that British sword stayed with him forever. So did his hatred of the British. How would you feel after such a year? And what did Andrew do next?

killed in battle in 1779. Elizabeth encouraged Robert and Andrew to attend local militia drills; they soon became couriers; but were captured by the British in April 1781 (Andrew was 14). They were not good POW’s – Andrew refused to clean an officer’s boots; the officer’s sword quickly slashed his face and hand; it left Andrew with scars and an intense hatred for the British. The story doesn’t get prettier; both boys contracted smallpox and almost starved in captivity. Elizabeth somehow managed to secure their release; the three began walking the 40 miles back home when a torrential downpour began. Two days after returning home, Robert was dead and Andrew terribly ill. After nursing Andrew back to health, Elizabeth volunteered to nurse American prisoners of war on board two British ships in the Charleston harbor, where there had been an outbreak of cholera. She died from the disease in November and is buried in an unmarked grave. By the end of 1781, Andrew was an orphan. Summary of his 14th year – he suffered captivity by the British, near starvation, the disease of smallpox, and the loss of two brothers and his mother. The scars from his smallpox and that British sword stayed with him forever. So did his hatred of the British. How would you feel after such a year? And what did Andrew do next?

On To Rachel, and Orphans

Andrew made do. He boarded with various people, went to a local school, tried saddle making, and studied with enough lawyers to be admitted to the bar in North Carolina in 1787, at the age of 20. Then Andrew headed west; he got a job as a prosecutor in western North Carolina; he bought his first slave, fought his first duel, and moved on to Nashville, a small frontier town, in 1788. That’s where he met Rachel. Rachel Donelson Robards (1767-1828) was married at the time; an unhappy marriage. The story goes that she divorced Captain Robards, and married Andrew in 1791 – they were both 24. It seems Rachel’s divorce wasn’t final however and she and Andrew were in a bigamous relationship; they did a redo and married for the second time in 1794. Evidence shows that Rachel was living with Andrew before the petition for divorce was ever made; a fact that was raked over the coals during Andrew’s presidential campaign. His love for Rachel is a “once is enough” romance, with many happy days but a tragic end. Rachel often struggled while Andrew was away, but she began experiencing significant physical stress during the election season. She died of a heart attack on December 22, 1828, 10 weeks before her husband took office as president. Andrew literally had to be pulled from her side so the undertaker could prepare the body. Believing that the abuse from John Quincy Adams’ supporters hastened her death, Andrew swore at her funeral, “May God Almighty forgive her murderers. I never can.”

Andrew made do. He boarded with various people, went to a local school, tried saddle making, and studied with enough lawyers to be admitted to the bar in North Carolina in 1787, at the age of 20. Then Andrew headed west; he got a job as a prosecutor in western North Carolina; he bought his first slave, fought his first duel, and moved on to Nashville, a small frontier town, in 1788. That’s where he met Rachel. Rachel Donelson Robards (1767-1828) was married at the time; an unhappy marriage. The story goes that she divorced Captain Robards, and married Andrew in 1791 – they were both 24. It seems Rachel’s divorce wasn’t final however and she and Andrew were in a bigamous relationship; they did a redo and married for the second time in 1794. Evidence shows that Rachel was living with Andrew before the petition for divorce was ever made; a fact that was raked over the coals during Andrew’s presidential campaign. His love for Rachel is a “once is enough” romance, with many happy days but a tragic end. Rachel often struggled while Andrew was away, but she began experiencing significant physical stress during the election season. She died of a heart attack on December 22, 1828, 10 weeks before her husband took office as president. Andrew literally had to be pulled from her side so the undertaker could prepare the body. Believing that the abuse from John Quincy Adams’ supporters hastened her death, Andrew swore at her funeral, “May God Almighty forgive her murderers. I never can.”

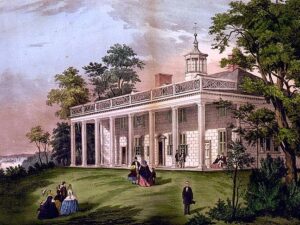

Andrew and Rachel never had children together but adopted, or cared for “a lot of kids” in their Nashville home, The Hermitage. In 1808, they took in one of the infant twins of Rachel’s brother Severn Donelson, and raised him as their own. They named him Andrew

Andrew and Rachel never had children together but adopted, or cared for “a lot of kids” in their Nashville home, The Hermitage. In 1808, they took in one of the infant twins of Rachel’s brother Severn Donelson, and raised him as their own. They named him Andrew  Jackson Jr. (1808-1865). When Rachel’s brother Samuel Donelson died in 1804 they cared for his three sons — John Samuel, Andrew Jackson, and Daniel. When Andrew found a Native American child on the battlefield with his dead mother in 1813, he brought him to the Hermitage, named him Lyncoya, and raised and educated him along with Andrew Jr. Andrew Jackson Hutchings, grandson of Rachel’s sister, lost both parents when he was five; he too was brought to the Hermitage and attended school with Andrew Jr and Lyncoya. Quite a legacy for one who was orphaned at an early age himself.

Jackson Jr. (1808-1865). When Rachel’s brother Samuel Donelson died in 1804 they cared for his three sons — John Samuel, Andrew Jackson, and Daniel. When Andrew found a Native American child on the battlefield with his dead mother in 1813, he brought him to the Hermitage, named him Lyncoya, and raised and educated him along with Andrew Jr. Andrew Jackson Hutchings, grandson of Rachel’s sister, lost both parents when he was five; he too was brought to the Hermitage and attended school with Andrew Jr and Lyncoya. Quite a legacy for one who was orphaned at an early age himself.

The Battles

This tender man who cared for so many children in need also fought in four different wars – the Revolutionary War, the Creek War, the War of 1812, and the First Seminole War. I’ll let you look those up yourself to read about his fierceness, campaign strategies, and tough leadership skills; there is much written about him as “War Hero.” He, like George Washington and James Monroe, got back up and kept fighting, no matter how many times he was down. He earned the nickname “Old Hickory” because he was a strict and bold military officer, unbending as a tree, and tough as wood.

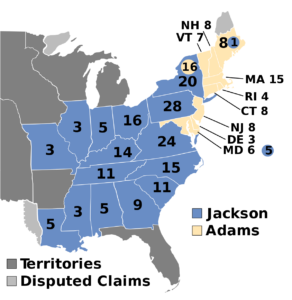

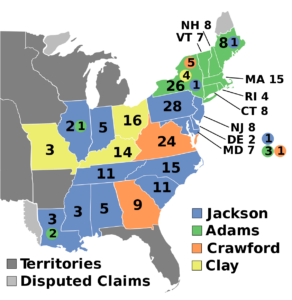

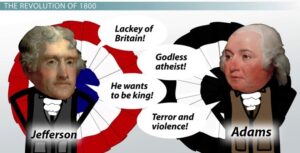

He ran for president in 1824, winning the most popular and electoral votes. But that was a battle he LOST. Since no candidate won an electoral majority, the House of Representatives elected John Quincy Adams in a contingent election. In the years ahead, Andrew Jackson repeatedly called for the abolition of the Electoral College, recommending “giving the election of President and Vice-President to the people.”

He ran for president in 1824, winning the most popular and electoral votes. But that was a battle he LOST. Since no candidate won an electoral majority, the House of Representatives elected John Quincy Adams in a contingent election. In the years ahead, Andrew Jackson repeatedly called for the abolition of the Electoral College, recommending “giving the election of President and Vice-President to the people.”

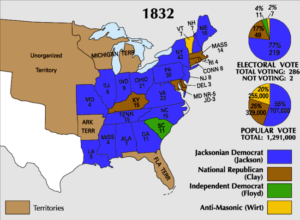

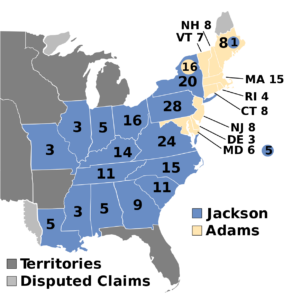

The Tennessee legislature didn’t waste any time in nominating Andrew for president again – they did it more than three years before the 1828 election, the earliest nomination in presidential history. The campaign was personal, and mean; the candidates didn’t campaign but the press stayed on it, calling Andrew Jackson a slave trader and a cannibal (eating the bodies of Indians killed in battle); they called his mother a prostitute and his father a mulatto; and of course, there was that “bigamy” issue about Rachel. Karma again did what Karma does – Andrew Jackson received 178 electoral votes to John Quincy Adams’ 83. And for the second time, an outgoing president did not attend the new president’s inauguration.

The Tennessee legislature didn’t waste any time in nominating Andrew for president again – they did it more than three years before the 1828 election, the earliest nomination in presidential history. The campaign was personal, and mean; the candidates didn’t campaign but the press stayed on it, calling Andrew Jackson a slave trader and a cannibal (eating the bodies of Indians killed in battle); they called his mother a prostitute and his father a mulatto; and of course, there was that “bigamy” issue about Rachel. Karma again did what Karma does – Andrew Jackson received 178 electoral votes to John Quincy Adams’ 83. And for the second time, an outgoing president did not attend the new president’s inauguration.

Neither did Andrew’s wife of course. On March 4, 1829, ten weeks after her Christmas Eve  funeral at the Hermitage, Andrew Jackson became the first president-elect to take the oath of office on the East Portico of the US Capitol. At the end of the ceremony, he invited the public to the White House for a party. This “common man of the people” spent his first day as president surrounded by thousands of people living it up in the White House; the staff was overwhelmed and fixtures and furnishings were damaged.

funeral at the Hermitage, Andrew Jackson became the first president-elect to take the oath of office on the East Portico of the US Capitol. At the end of the ceremony, he invited the public to the White House for a party. This “common man of the people” spent his first day as president surrounded by thousands of people living it up in the White House; the staff was overwhelmed and fixtures and furnishings were damaged.

The second inauguration of Andrew Jackson took place in the House Chamber of the US Capitol on March 4, 1833. It was held inside because the temperature was 29 degrees, there was snow on the ground, and Andrew’s health was poor. His private secretary, Andrew  Jackson Donelson, stood on his right during the swearing in. Remember him? One of Rachel’s nephews that he raised. Martin Van Buren, the new vice president, stood to the left. No mob parties at the White House this time; but two inaugural balls. That evening there were 50-gun salutes at 9 PM and at midnight. Andrew won this time with 219 electoral votes to Clay’s 49. The country had grown to 24 states, and at that moment in time, was not in conflict with any nation.

Jackson Donelson, stood on his right during the swearing in. Remember him? One of Rachel’s nephews that he raised. Martin Van Buren, the new vice president, stood to the left. No mob parties at the White House this time; but two inaugural balls. That evening there were 50-gun salutes at 9 PM and at midnight. Andrew won this time with 219 electoral votes to Clay’s 49. The country had grown to 24 states, and at that moment in time, was not in conflict with any nation.

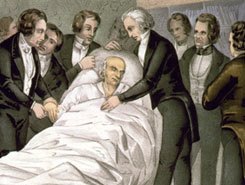

Andrew retired to the Hermitage in 1837, and though in poor health, he remained influential in national and state politics. On June 8, 1845, surrounded by family and friends, he died of heart failure at the age of 78. Historian Charles Grier Sellers wrote about him: “There has never been universal agreement on Jackson’s legacy, for his opponents have ever been his most bitter enemies, and his friends almost his worshippers.”

His Government Positions

- Member of U.S. House of Representatives, 1796-97

- United States Senator, 1797-98

- Justice on Tennessee Supreme Court, 1798-1804

- Governor of the Florida Territory, 1821

- United States Senator, 1823-25

- Seventh President of the United States, 1829-1837

My maternal grandfather, born in the late 1800s, was named after Andrew Jackson. My grandfather also was orphaned at an early age – his mother died when he was four; his father when he was fourteen. I find him on the US Census at age 16, boarding with one of his brothers at the home of a man who owned a sawmill.

Isn’t that ironic?

» June 20th, 2024

#6. Adams, John Quincy

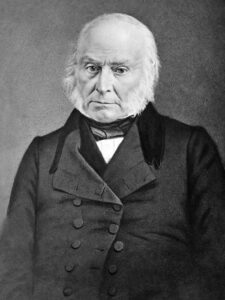

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – John Quincy Adams (July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was the sixth president of the United States (1825 to 1829) and the eldest son of John and Abigail Adams, two big names in American history. Which puts him in the same situation as being a “preacher’s kid” – you know, everybody expects a certain behavior from you. No matter what you do, or want to do, the jello is already set. John Q certainly emulated his father in a number of ways – he was a one-termer president, he loved politics, and he WROTE EVERYTHING DOWN. He started keeping a daily diary when he was 12 and didn’t stop until he died. Here is an example of an entry from July 1818, when he was 51 years old, and Secretary of State in James Monroe’s cabinet: “I rise usually between four and five — walk two miles, bathe in Potowmack river, and walk home, which occupies two hours — read or write, or more frequently idly waste the time till eight or nine when we breakfast— read or write till twelve or one, when I go to the office; now usually in the carriage — at the office till five then home till dinner. After dinner read newspapers till dark; soon after which I retire to bed.” Would you invite this man to your party? Would he come? Possibly, but only if it was a swim party, and everyone was okay with swimming nude. Because skinny dipping was the way people swam! You folded your clothes, laid them on the riverbank, and jumped in. The “swimming nude in the Potomac” presidential folktale is an actual truth; some of the others are not verifiable.

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – John Quincy Adams (July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was the sixth president of the United States (1825 to 1829) and the eldest son of John and Abigail Adams, two big names in American history. Which puts him in the same situation as being a “preacher’s kid” – you know, everybody expects a certain behavior from you. No matter what you do, or want to do, the jello is already set. John Q certainly emulated his father in a number of ways – he was a one-termer president, he loved politics, and he WROTE EVERYTHING DOWN. He started keeping a daily diary when he was 12 and didn’t stop until he died. Here is an example of an entry from July 1818, when he was 51 years old, and Secretary of State in James Monroe’s cabinet: “I rise usually between four and five — walk two miles, bathe in Potowmack river, and walk home, which occupies two hours — read or write, or more frequently idly waste the time till eight or nine when we breakfast— read or write till twelve or one, when I go to the office; now usually in the carriage — at the office till five then home till dinner. After dinner read newspapers till dark; soon after which I retire to bed.” Would you invite this man to your party? Would he come? Possibly, but only if it was a swim party, and everyone was okay with swimming nude. Because skinny dipping was the way people swam! You folded your clothes, laid them on the riverbank, and jumped in. The “swimming nude in the Potomac” presidential folktale is an actual truth; some of the others are not verifiable.

For instance, the “pet alligator in the White House” simply hasn’t been proven, any more than George Washington’s Hatchett Attacks Cherry Tree story. Maybe LaFayette did give him a baby alligator once – certainly White House occupants are gifted with many unusual objects. Maybe it was kept in the bathtub to surprise guests. But the joke doesn’t really fit into the austere tone of his diary-speak, does it? Still, gift shops sell stuffed alligators as “White House pets.” Let’s switch to serious stuff now. What was John Q’s childhood like?

The Boy

For starters, his stomach was a little unsettled when his father committed an act of TREASON by signing the Declaration of Independence in 1776. This was a crime punishable by death, and John Q was nine years old at the time. While Dad was off on his “revolution” cause, John Q was at home worrying about his mother Abigail – she was a sweetie – and his siblings; sister Amelia was 11, brothers Charles and Thomas were 6 and 4. As “man of the house” John Q worried for their safety. A war went on around his very ears; he actually witnessed the Battle of Bunker Hill with his mother, from the top of a nearby hill. As soldiers passed through town, he feared they might be taken hostage. That was his reality. How would you feel in the middle of all that?

For starters, his stomach was a little unsettled when his father committed an act of TREASON by signing the Declaration of Independence in 1776. This was a crime punishable by death, and John Q was nine years old at the time. While Dad was off on his “revolution” cause, John Q was at home worrying about his mother Abigail – she was a sweetie – and his siblings; sister Amelia was 11, brothers Charles and Thomas were 6 and 4. As “man of the house” John Q worried for their safety. A war went on around his very ears; he actually witnessed the Battle of Bunker Hill with his mother, from the top of a nearby hill. As soldiers passed through town, he feared they might be taken hostage. That was his reality. How would you feel in the middle of all that?

Things got immensely better; an Incredible European Adventure began in 1778 when his father was posted as a special envoy; John Q went to school at the Passy Academy outside of Paris, where, get this – he studied fencing, dance, music, and art with the grandsons of Benjamin Franklin. But things were still a bit quirky; Dad went back to the US, and then back to Europe again as negotiations continued; their ship was leaky; they traveled overland by mule through Spain; some time in Paris but then to Amsterdam, where John Q and Charles briefly studied at the University of Leiden. Charles wanted to go back home, but John Q, at the age of 14, was invited to go to St Petersburg as “translator and personal secretary” to Francis Dana, the newly appointed emissary there. I’d love to read all the diary entries for that period of John Q’s life! Back to The Hague with his father for a while, and in 1785, at the age of 16, he entered Harvard College as an advanced student and completed his studies in two years.

Things got immensely better; an Incredible European Adventure began in 1778 when his father was posted as a special envoy; John Q went to school at the Passy Academy outside of Paris, where, get this – he studied fencing, dance, music, and art with the grandsons of Benjamin Franklin. But things were still a bit quirky; Dad went back to the US, and then back to Europe again as negotiations continued; their ship was leaky; they traveled overland by mule through Spain; some time in Paris but then to Amsterdam, where John Q and Charles briefly studied at the University of Leiden. Charles wanted to go back home, but John Q, at the age of 14, was invited to go to St Petersburg as “translator and personal secretary” to Francis Dana, the newly appointed emissary there. I’d love to read all the diary entries for that period of John Q’s life! Back to The Hague with his father for a while, and in 1785, at the age of 16, he entered Harvard College as an advanced student and completed his studies in two years.

After college, John Q studied law; while preparing for the exam he mastered shorthand and read everything in sight; he passed the bar in 1790 and set up a practice in Boston. Business was slow; he wrote a lot during this time – articles supporting the Washington administration; political issues of the day. It paid off in an unexpected way – Washington, aware of John Q’s support, and his fluency in French and Dutch, appointed him minister to the Netherlands. What a career followed!

Adding Up His Government Positions

- Secretary to US Minister to Russia, 1781

- Minister to the Netherlands, 1794

- Minister to Prussia, 1797-1801

- United States Senator, 1803-08

- Minister to Russia, 1809-11

- Peace Commissioner at Treaty of Ghent, 1814

- Secretary of State, 1817-25 (under Monroe)

- President, 1825-1829

- Member of US House of Representatives, 1831-48

Important to note that workaholic John Q spent 17 years in Congress AFTER he was president. He was 78 when he had a stroke, but he recovered and kept on working. When he entered the House chamber on February 13, 1848, everyone stood and applauded. Then on February 21, as the House members discussed honoring Army officers who served in the Mexican-American War, John Q, who had been a vehement critic of the war, stood to shout “No!” He then collapsed, having suffered a massive cerebral hemorrhage. He died in the Speaker’s Room in the Capitol two days later, his wife by his side. His last words were “I am content.” Someone else there that day was a freshman representative from Illinois, Abraham Lincoln.

Important to note that workaholic John Q spent 17 years in Congress AFTER he was president. He was 78 when he had a stroke, but he recovered and kept on working. When he entered the House chamber on February 13, 1848, everyone stood and applauded. Then on February 21, as the House members discussed honoring Army officers who served in the Mexican-American War, John Q, who had been a vehement critic of the war, stood to shout “No!” He then collapsed, having suffered a massive cerebral hemorrhage. He died in the Speaker’s Room in the Capitol two days later, his wife by his side. His last words were “I am content.” Someone else there that day was a freshman representative from Illinois, Abraham Lincoln.

Love and Marriage and The Screaming Press

John Q met Louisa Catherine Johnson (1775-1852) in 1779 when she was four and he was traveling in France. Her father Joshua was an American merchant who married an Englishwoman; they were living in Nantes, France. Years later, John Q and Louisa met again – he was a 30-year old diplomat and son of the President of the US; she was living in London, where her father was serving as the American consul. John Q had been sent to London from The Hague to exchange the ratifications of the Jay Treaty. The Johnson home was the social center for Americans in London and John Q visited regularly; in time he began dining nightly with the family and the spark was lit. Neither set of parents approved of their marriage; Louisa’s father worried that Yankees made poor husbands; John Q’s mother Abigail worried about the effect a “foreign-born wife” would have on his political dreams. Ahhh. They married on July 26, 1797 in the United Kingdom, and American papers lit in right away. As Abigail Adams had foreseen, Louisa was forced to spend much of her husband’s time in office defending not just their union, but also her loyalty to the Union. The couple lived in Europe until after the birth of their first son; Louisa Adams did not set foot on American soil until she was 26.

John Q met Louisa Catherine Johnson (1775-1852) in 1779 when she was four and he was traveling in France. Her father Joshua was an American merchant who married an Englishwoman; they were living in Nantes, France. Years later, John Q and Louisa met again – he was a 30-year old diplomat and son of the President of the US; she was living in London, where her father was serving as the American consul. John Q had been sent to London from The Hague to exchange the ratifications of the Jay Treaty. The Johnson home was the social center for Americans in London and John Q visited regularly; in time he began dining nightly with the family and the spark was lit. Neither set of parents approved of their marriage; Louisa’s father worried that Yankees made poor husbands; John Q’s mother Abigail worried about the effect a “foreign-born wife” would have on his political dreams. Ahhh. They married on July 26, 1797 in the United Kingdom, and American papers lit in right away. As Abigail Adams had foreseen, Louisa was forced to spend much of her husband’s time in office defending not just their union, but also her loyalty to the Union. The couple lived in Europe until after the birth of their first son; Louisa Adams did not set foot on American soil until she was 26.

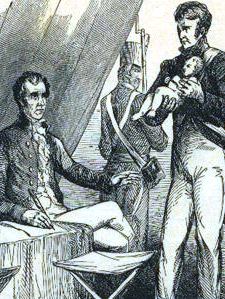

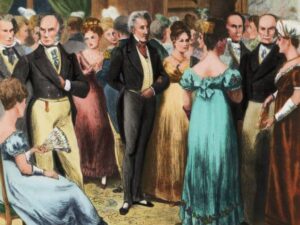

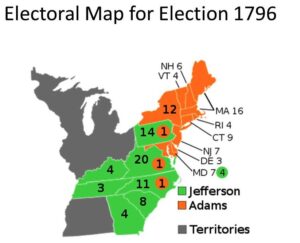

Louisa Adams was sophisticated and urbane; John Q had ambitious political aims, but lacked charisma. She saw herself as his “diplomat,” and became the dominant hostess of Washington, holding balls and parties to raise his social status. (Andrew Jackson is in the center of the painting, John Q to the left) She watched Congress debate, read newspapers, and advised her husband. It worked, to an extent; he was elected president in 1824 but it was a raunchy deal; John Q lost both the popular vote and the electoral votes to Andrew Jackson; but since there was no majority of electoral votes, John Q made a deal with Henry Clay, promising an

Louisa Adams was sophisticated and urbane; John Q had ambitious political aims, but lacked charisma. She saw herself as his “diplomat,” and became the dominant hostess of Washington, holding balls and parties to raise his social status. (Andrew Jackson is in the center of the painting, John Q to the left) She watched Congress debate, read newspapers, and advised her husband. It worked, to an extent; he was elected president in 1824 but it was a raunchy deal; John Q lost both the popular vote and the electoral votes to Andrew Jackson; but since there was no majority of electoral votes, John Q made a deal with Henry Clay, promising an  appointment as Secretary of State if he’d bring in a block of southern-midwestern states. With Clay’s backing, Adams won the contingent election on the first ballot. Louisa did not approve the deal and did not attend her husband’s inauguration.

appointment as Secretary of State if he’d bring in a block of southern-midwestern states. With Clay’s backing, Adams won the contingent election on the first ballot. Louisa did not approve the deal and did not attend her husband’s inauguration.

For the four years of his presidency, every aspect of their lives was placed under media scrutiny. Louisa was painted in the press as a foreigner and a Tory of aristocratic birth. She came back describing herself as “the daughter of an American Republican merchant.” The Adams were accused of living like “European royalty” and there was even mention of a “first lady sex scandal with a Russian czar.” It kept them in the papers!  Louisa believed that voters were swayed by their emotions, rather than rational reasoning. (Imagine that!) Shortly before her husband sought reelection, she defended herself in print. She dismissed charges of impropriety and reemphasized the American citizenship she had been born with. It wasn’t enough; during John Q’s presidency, the Democratic-Republican Party split; the Democrats who supported Jackson proved to be more effective political organizers than the Republicans who supported Adams; Jackson decisively won, receiving 178 electoral votes to Adams’ 83.

Louisa believed that voters were swayed by their emotions, rather than rational reasoning. (Imagine that!) Shortly before her husband sought reelection, she defended herself in print. She dismissed charges of impropriety and reemphasized the American citizenship she had been born with. It wasn’t enough; during John Q’s presidency, the Democratic-Republican Party split; the Democrats who supported Jackson proved to be more effective political organizers than the Republicans who supported Adams; Jackson decisively won, receiving 178 electoral votes to Adams’ 83.

Historians generally concur that John Quincy Adams was one of the greatest diplomats and secretaries of state in American history; though they typically rank him as a mediocre president. He had an ambitious agenda but could not get it passed by Congress.

Historians generally concur that John Quincy Adams was one of the greatest diplomats and secretaries of state in American history; though they typically rank him as a mediocre president. He had an ambitious agenda but could not get it passed by Congress.

Do you see sadness reflected in his eyes in Matthew Brady’s “first photograph” of a president? Perhaps, but John Quincy Adams’ life was filled with adventure, romance, and a great swimming hole, worthy of a Mark Twain tale. His last three words were “I am content.”

Maybe he DID have a pet alligator.

» June 19th, 2024

#5. Monroe, James

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – James Monroe (April 28, 1758 – July 4, 1831) was the fifth president of the United States (1817 to 1825) and the last president of the “Virginia dynasty.” He was also the last US president to wear a powdered wig tied in a queue, a tricorn hat, and knee-breeches. He was the last president to have never been photographed, though he does appear in some famous paintings you’ve seen. You probably didn’t realize you were looking at him, but James Monroe was in the scene of revolutionary action, and getting the country settled down action, working hard, doing his part. He saw what had to be done, and he did it. Yes, he was with George from the beginning, and we know how feisty George was – like getting bullet holes in his hat, and coat. But James got a bullet in his SHOULDER, and kept on fighting. Would James come to your party? Possibly, if you let him bring his gun. This guy grabbed up a few cannons from the Governor’s House in Williamsburg once, although technically that wasn’t a party; it was more an attack. But let’s get back to those portraits.

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – James Monroe (April 28, 1758 – July 4, 1831) was the fifth president of the United States (1817 to 1825) and the last president of the “Virginia dynasty.” He was also the last US president to wear a powdered wig tied in a queue, a tricorn hat, and knee-breeches. He was the last president to have never been photographed, though he does appear in some famous paintings you’ve seen. You probably didn’t realize you were looking at him, but James Monroe was in the scene of revolutionary action, and getting the country settled down action, working hard, doing his part. He saw what had to be done, and he did it. Yes, he was with George from the beginning, and we know how feisty George was – like getting bullet holes in his hat, and coat. But James got a bullet in his SHOULDER, and kept on fighting. Would James come to your party? Possibly, if you let him bring his gun. This guy grabbed up a few cannons from the Governor’s House in Williamsburg once, although technically that wasn’t a party; it was more an attack. But let’s get back to those portraits.

Where is Monroe?

The Emanuel Leutze portrait of Washington Crossing the Delaware in 1776 wasn’t done until 1851, and is acknowledged to be mostly inaccurate, though quite inspiring. George Washington is in fine form, on a cold and stormy night. But who is holding onto the flag? That is meant to be James Monroe, did you know? In reality, that flag didn’t exist yet, and James Monroe wasn’t on the same boat as George Washington – he had come across hours earlier. But it’s a good story. John Trumbull’s Capture of the Hessians at Trenton is an even better story, I think. Karma on its best behavior! The time of the event portrayed is a few hours after the landing; Monroe’s regiment is sneaking through the snowy countryside when spotted by some dogs, who did what dogs do, and awakened their master, John Riker. He thought they were British, and began shouting at them; when he learned they were Americans he volunteered to join them immediately. “I am a doctor and I may be able to help,” he said. Early in the battle while charging Hessian cannons, Monroe was shot down. A musket ball pierced his chest, lodged in his shoulder, and severed an artery. Dr Riker clamped the artery and stopped the bleeding; James Monroe got up and continued fighting. And eventually became our fifth president, ha! In the portrait, James is the one on the ground holding onto his shoulder, as you might guess. And do the math – he was only 18 years old!

The Emanuel Leutze portrait of Washington Crossing the Delaware in 1776 wasn’t done until 1851, and is acknowledged to be mostly inaccurate, though quite inspiring. George Washington is in fine form, on a cold and stormy night. But who is holding onto the flag? That is meant to be James Monroe, did you know? In reality, that flag didn’t exist yet, and James Monroe wasn’t on the same boat as George Washington – he had come across hours earlier. But it’s a good story. John Trumbull’s Capture of the Hessians at Trenton is an even better story, I think. Karma on its best behavior! The time of the event portrayed is a few hours after the landing; Monroe’s regiment is sneaking through the snowy countryside when spotted by some dogs, who did what dogs do, and awakened their master, John Riker. He thought they were British, and began shouting at them; when he learned they were Americans he volunteered to join them immediately. “I am a doctor and I may be able to help,” he said. Early in the battle while charging Hessian cannons, Monroe was shot down. A musket ball pierced his chest, lodged in his shoulder, and severed an artery. Dr Riker clamped the artery and stopped the bleeding; James Monroe got up and continued fighting. And eventually became our fifth president, ha! In the portrait, James is the one on the ground holding onto his shoulder, as you might guess. And do the math – he was only 18 years old!

In The Beginning

When I look over all the things James Monroe did, I see a man who believed it was his job to take action when action was called for. Yes, he was born into the “Virginia Planter” way of life, but it was vastly different for him than it was for Washington, Jefferson, and Madison. They inherited vast estates, with thousands of acres of Virginia land and hundreds of slaves, and began their extensive educations at an early age. Even Adams, who only wound up with an 8-acre farm in Massachusetts, had a father who INSISTED that he attend school – “You shall comply with my desires,” he was told, after a bout of truancy. It wasn’t like that for James Monroe. His father, Spence Monroe, was a moderately prosperous planter, and a carpenter; his mother Elizabeth Jones died when James was 14; his father died when he was 16. Although James began attending the only school in the county at age 11, it was just for a few weeks a year – he was needed to work on the farm. When his parents died he inherited property from them, but withdrew from school to help care for his younger brothers. James was second born of five children – Elizabeth, then James, Spence, Andrew, and Joseph. His childless maternal uncle, Joseph Jones, became a surrogate father; he enrolled James in the College of William & Mary and introduced him to George Washington, Patrick Henry, and Thomas Jefferson. But it was 1774, and opposition to the British government was getting hotter and hotter. James dropped out of school and joined the fight. The Governor’s Palace in Williamsburg was one of the first hits (cannons, remember?) He served in the Continental Army (under George Washington), studied law (under Thomas Jefferson), and there was no stopping him from there.

Other Government Positions:

- Member of Continental Congress, 1783-86

- United States Senator, 1790-94

- Minister to France, 1794-96

- Governor of Virginia, 1799-1802

- Minister to France and England, 1803-07

- Secretary of State, 1811-17 (under Madison)

- Secretary of War, 1814-15 (under Madison)

- Fifth President of the United States, 1817-1825

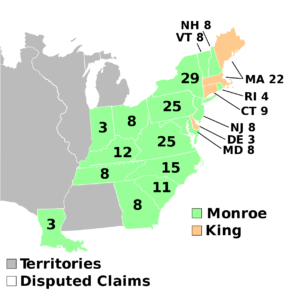

Note that he was Secretary of State AND Secretary of War at the same time in Madison’s cabinet; after that little fiasco in 1814 when Washington DC was set on fire by the British, Madison fired Secretary of War John Armstrong and turned to Monroe for help; Monroe asked Congress to draft an army of 100,000 men and to increase compensation for soldiers. His wartime leadership established him as Madison’s heir apparent, and he easily defeated Federalist Party candidate Rufus King in the 1816 presidential election. – 183 electoral votes to Rufus King’s 34.

Note that he was Secretary of State AND Secretary of War at the same time in Madison’s cabinet; after that little fiasco in 1814 when Washington DC was set on fire by the British, Madison fired Secretary of War John Armstrong and turned to Monroe for help; Monroe asked Congress to draft an army of 100,000 men and to increase compensation for soldiers. His wartime leadership established him as Madison’s heir apparent, and he easily defeated Federalist Party candidate Rufus King in the 1816 presidential election. – 183 electoral votes to Rufus King’s 34.

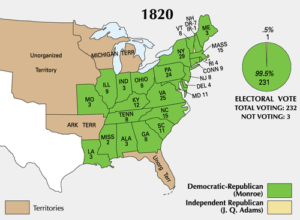

James Monroe’s presidency was a time of establishing order and bringing things into alignment; he ignored old party lines in making appointments; he made two long national tours to build national trust. Five new states were admitted to the Union — Mississippi 1817, Illinois 1818, Alabama 1819, Maine 1820, Missouri 1821. The 49th Parallel was established as the border with Canada; the Missouri Compromise forbade slavery above 36 degrees 30 minutes latitude; Spain ceded Florida to the United States. The General Survey Act authorized surveys of routes for roads and canals “necessary for the transportation of public mail.” On  December 23, 1823, in his annual message to Congress, he stated, among many other things regarding neutrality in world affairs, that European countries should no longer consider the Western Hemisphere open to new colonization. “Listen to me!” he said to the world. Those declarations are known today as the Monroe Doctrine. He won the 1820 election ALMOST unanimously – 1 vote was cast for John Quincy Adams.

December 23, 1823, in his annual message to Congress, he stated, among many other things regarding neutrality in world affairs, that European countries should no longer consider the Western Hemisphere open to new colonization. “Listen to me!” he said to the world. Those declarations are known today as the Monroe Doctrine. He won the 1820 election ALMOST unanimously – 1 vote was cast for John Quincy Adams.

The Family Man

James got married while serving in the Continental Congress in New York – he met pretty Elizabeth Kortright (1768-1830) at the theater. Their wedding took place on February 16, 1786 – she was 18; he was 28. Her father was a wealthy trader; they lived with him until Congress adjourned; then they moved to Virginia and bought an estate in Charlottesville known as Ash Lawn. They had three children: Eliza was born in 1786 and educated in Paris during the time James was Ambassador to France; James Spence was born in 1799, but only lived sixteen months; Maria was born in 1804. She was the first “president’s child” to marry in the White House! Oh yes – the White House was reconstructed by 1817; the Monroes brought many of their own furnishings when they moved in as everything had been lost in the 1814 fire. Elizabeth’s health was delicate so the daughters had to help with entertaining; Elizabeth and Eliza leaned to a more exclusive and formal French style, nothing like the Dolley Madison era. Not much is known about the nature of the relationship between James and Elizabeth; all private correspondence was burned before their deaths.

James got married while serving in the Continental Congress in New York – he met pretty Elizabeth Kortright (1768-1830) at the theater. Their wedding took place on February 16, 1786 – she was 18; he was 28. Her father was a wealthy trader; they lived with him until Congress adjourned; then they moved to Virginia and bought an estate in Charlottesville known as Ash Lawn. They had three children: Eliza was born in 1786 and educated in Paris during the time James was Ambassador to France; James Spence was born in 1799, but only lived sixteen months; Maria was born in 1804. She was the first “president’s child” to marry in the White House! Oh yes – the White House was reconstructed by 1817; the Monroes brought many of their own furnishings when they moved in as everything had been lost in the 1814 fire. Elizabeth’s health was delicate so the daughters had to help with entertaining; Elizabeth and Eliza leaned to a more exclusive and formal French style, nothing like the Dolley Madison era. Not much is known about the nature of the relationship between James and Elizabeth; all private correspondence was burned before their deaths.

When his presidency ended on March 4, 1825, James and Elizabeth lived at Oak Hill in Aldie, Virginia, until her death at age 62 in 1830. James moved to New York then, to live with daughter Maria and her husband; he died at age 73 of heart failure and tuberculosis – on July 4, 1831. Make note: he was the THIRD president to die on July 4 – such an unusual connection between three of our Founding Fathers.

Firsts

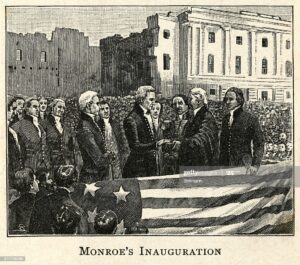

I began with “lasts” about James Monroe; here are a few “firsts.” He was the first president to ride on a steamboat. He was the first president to have been a US Senator. His 1817 inauguration was the first to be held outside. He was the first president to win all but ONE electoral votes. Sure, Washington got ALL electoral votes once, but All-But-One is pretty darn good as there were lots more people voting and getting the hang of it!

I began with “lasts” about James Monroe; here are a few “firsts.” He was the first president to ride on a steamboat. He was the first president to have been a US Senator. His 1817 inauguration was the first to be held outside. He was the first president to win all but ONE electoral votes. Sure, Washington got ALL electoral votes once, but All-But-One is pretty darn good as there were lots more people voting and getting the hang of it!

Just as he was not “center stage” in the portraits mentioned earlier, James Monroe sometimes suffers from comparison to the other members of the Virginia Dynasty. He may not be as beloved as George Washington, or the Renaissance man that Thomas Jefferson was. But he was a great advocate of nationalism and reached out to all regions of the country. He had the ability to look at issues from all sides, encouraging debate. In foreign policy he put the nation on an independent course.

I see him as a man who tried to make a difference, and did.

» June 18th, 2024

#4. Madison, James

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – James Madison (March 16, 1751 – June 28, 1836) was the fourth president of the United States (1809 to 1817) and the third Virginia planter to be elected. But James has a very special distinction nobody else comes close to — he was the SMALLEST president ever. No kidding, he was 5’4″ and weighed barely 100 pounds. In addition, he was very soft spoken. Despite what might be considered weaknesses, he was a close advisor to George Washington, and the main force behind the ratification of the Bill of Rights. He wound up being remembered as the “Father of the Constitution”! But even more startling for such a diminutive fellow, he is the only president who started a war, and then, with no military experience whatsoever, rode his horse onto the battlefield under fire! Would you want this guy at your party? You would if he brought Dolley. His pretty wife Dolley knew how to get people together, and get them talking. She was a great hostess; the first real “first lady” in the White House. She was so charming that she sometimes served as hostess for President Thomas Jefferson (remember, he was a widower), before she lived in the White House herself. Dolley loved the White House and really made the history books for something she did on August 24, 1814.

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – James Madison (March 16, 1751 – June 28, 1836) was the fourth president of the United States (1809 to 1817) and the third Virginia planter to be elected. But James has a very special distinction nobody else comes close to — he was the SMALLEST president ever. No kidding, he was 5’4″ and weighed barely 100 pounds. In addition, he was very soft spoken. Despite what might be considered weaknesses, he was a close advisor to George Washington, and the main force behind the ratification of the Bill of Rights. He wound up being remembered as the “Father of the Constitution”! But even more startling for such a diminutive fellow, he is the only president who started a war, and then, with no military experience whatsoever, rode his horse onto the battlefield under fire! Would you want this guy at your party? You would if he brought Dolley. His pretty wife Dolley knew how to get people together, and get them talking. She was a great hostess; the first real “first lady” in the White House. She was so charming that she sometimes served as hostess for President Thomas Jefferson (remember, he was a widower), before she lived in the White House herself. Dolley loved the White House and really made the history books for something she did on August 24, 1814.

A Wild Story

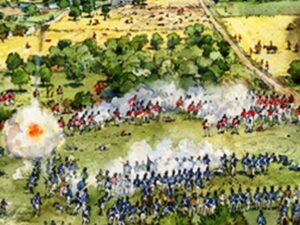

Another war with those pesky British was going on; often called the Second War of Independence but officially the War of 1812. Around noon that day about 4,500 British marched within sight of Bladensburg, Maryland, nine miles NE of Washington. James Madison galloped onto the scene and proceeded to ride across a ridge overlooking the battlefield. According to the White House Historical Society and Dolley’s personal letters, James Madison had left the White House on August 22 to meet with his generals on the battlefield; the British troops were dangerously close to the capital. Before leaving, he asked Dolley if she had the “courage or firmness” to wait for his intended return the next day. He asked her to gather important state papers and be prepared to abandon the White House at any moment. Dolley started making lists and getting organized; she also

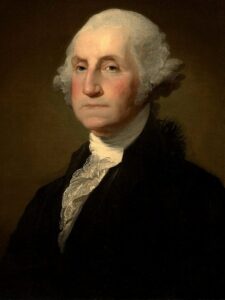

Another war with those pesky British was going on; often called the Second War of Independence but officially the War of 1812. Around noon that day about 4,500 British marched within sight of Bladensburg, Maryland, nine miles NE of Washington. James Madison galloped onto the scene and proceeded to ride across a ridge overlooking the battlefield. According to the White House Historical Society and Dolley’s personal letters, James Madison had left the White House on August 22 to meet with his generals on the battlefield; the British troops were dangerously close to the capital. Before leaving, he asked Dolley if she had the “courage or firmness” to wait for his intended return the next day. He asked her to gather important state papers and be prepared to abandon the White House at any moment. Dolley started making lists and getting organized; she also  prepared a “welcome back” dinner for James and the officers to enjoy on his return. I won’t go into all the shooting and shouting that happened on the battlefield that day, but the Americans were defeated, and the British marched into Washington and set it on fire. Dolley’s time for getting safely across the Potomac into Virginia was shortened to nearly nothing, but her determination kept her on track; the huge Stuart portrait of George Washington was cut from its frame (too many screws to be able to detach it from the wall); the canvas was rolled and saved. The White House emptied; the British entered, found the fine china, and gobbled up the nice dinner Dolley had prepared. After a bit of looting they set fire to the place.

prepared a “welcome back” dinner for James and the officers to enjoy on his return. I won’t go into all the shooting and shouting that happened on the battlefield that day, but the Americans were defeated, and the British marched into Washington and set it on fire. Dolley’s time for getting safely across the Potomac into Virginia was shortened to nearly nothing, but her determination kept her on track; the huge Stuart portrait of George Washington was cut from its frame (too many screws to be able to detach it from the wall); the canvas was rolled and saved. The White House emptied; the British entered, found the fine china, and gobbled up the nice dinner Dolley had prepared. After a bit of looting they set fire to the place.

The Americans’ defeat at Bladensburg was embarrassing, but that wasn’t the worst of it. Raiding parties set fire to the Capitol, the chambers of the Senate and House of Representatives, the Treasury Department, and the War Office, as well as the White House. The city was blazing. Dolley found her husband at their predetermined meeting place as a raging thunderstorm blew into the city. And that storm, actually defined as a hurricane, put out the fires. It also spun off a tornado that set down on Constitution Avenue and lifted two cannons before dropping them several yards away, killing some British troops and American civilians. The British returned to their ships, many of which were damaged. The rains sizzled and cracked the charred walls of the White House; the storm even destroyed some structures that had not been burned. Karma had a big night. An encounter was noted between a British officer and a female resident of Washington. She called out to him, “This is a special interposition of Providence to drive our enemies from our city,” to

The Americans’ defeat at Bladensburg was embarrassing, but that wasn’t the worst of it. Raiding parties set fire to the Capitol, the chambers of the Senate and House of Representatives, the Treasury Department, and the War Office, as well as the White House. The city was blazing. Dolley found her husband at their predetermined meeting place as a raging thunderstorm blew into the city. And that storm, actually defined as a hurricane, put out the fires. It also spun off a tornado that set down on Constitution Avenue and lifted two cannons before dropping them several yards away, killing some British troops and American civilians. The British returned to their ships, many of which were damaged. The rains sizzled and cracked the charred walls of the White House; the storm even destroyed some structures that had not been burned. Karma had a big night. An encounter was noted between a British officer and a female resident of Washington. She called out to him, “This is a special interposition of Providence to drive our enemies from our city,” to  which he replied, “Not so, Madam, it is rather to aid your enemies in the destruction of your city.” The Smithsonian reports there have only been seven other tornadoes recorded in Washington, DC in the 206 years since.

which he replied, “Not so, Madam, it is rather to aid your enemies in the destruction of your city.” The Smithsonian reports there have only been seven other tornadoes recorded in Washington, DC in the 206 years since.

The British occupation of Washington lasted only about 26 hours, and on December 24, 1814, the Treaty of Ghent formally ended the War of 1812. Although James and Dolley were able to return to Washington by September, they never again lived in the White House.

Enough About War

Let’s lighten the tone! What about James’ early days? He was born March 16, 1751 at Belle Grove Plantation near Port Conway, Virginia; the Madison family had lived in Virginia since the mid-1600s. James was the firstborn child of James Madison Sr, and Nelly Conway Madison; eleven more children followed, though only six lived to adulthood. James Sr was the largest landowner in the area –5,000 acres and 100 slaves. In the early 1760s they built “Montpelier,” which ultimately was James’ final resting place. Though James was small, he was a naturally curious and studious child; his education began at home under his mother; then he studied with a distinguished Scottish teacher – mathematics, geography, classical languages, philosophy.  Instead of moving on to William & Mary as most prominent Virginians did, he went north to the College of New Jersey (now Princeton); it was thought the climate would be better for his health than the humidity of coastal Williamsburg. He graduated in 1771 at the age of 20; but unsure about a vocation, he stayed on and kept studying – the college’s first “graduate student.” Although he studied law, he never practiced; but politics seemed an inevitable choice, as he always took an interest in how governments functioned. He started local, as a member of the Orange County Committee of Safety in 1774. From there it grew.

Instead of moving on to William & Mary as most prominent Virginians did, he went north to the College of New Jersey (now Princeton); it was thought the climate would be better for his health than the humidity of coastal Williamsburg. He graduated in 1771 at the age of 20; but unsure about a vocation, he stayed on and kept studying – the college’s first “graduate student.” Although he studied law, he never practiced; but politics seemed an inevitable choice, as he always took an interest in how governments functioned. He started local, as a member of the Orange County Committee of Safety in 1774. From there it grew.

Other Government Positions

- Member of Virginia Constitutional Convention, 1776

- Member of Continental Congress, 1780-83

- Member of Virginia Legislature, 1784-86

- Member of Constitutional Convention, 1787

- Member of U.S. House of Representatives, 1789-97

- Secretary of State, 1801-09 (under Jefferson)

- Fourth President of the United States, 1809-1817

The Family Man

Something besides politics caught James attention in 1794, when he was introduced to a young widow named Dolley Payne Todd (1768-1849) by a mutual acquaintance, Aaron Burr. She had recently lost her husband and youngest child in a yellow fever epidemic. James and Dolley were married within the year – he was 43, she was 26. James enjoyed a strong relationship with his wife; she became his political partner; he adopted her son John Payne Todd, who was two when they married.

Something besides politics caught James attention in 1794, when he was introduced to a young widow named Dolley Payne Todd (1768-1849) by a mutual acquaintance, Aaron Burr. She had recently lost her husband and youngest child in a yellow fever epidemic. James and Dolley were married within the year – he was 43, she was 26. James enjoyed a strong relationship with his wife; she became his political partner; he adopted her son John Payne Todd, who was two when they married.

When friend and colleague Thomas Jefferson named James Secretary of State in 1801, the Madisons moved to Washington; when Jefferson’s time in the White House came to a close, James Madison won the 1808 election with 122 electoral votes to Charles Pinckney’s 47. After the Madisons moved into the White House in 1809, both Dolley and James began working in their own unique ways to bring about compromises in a Congress that was divided. James attempted to balance the demands of Henry Clay’s War Hawks, who wanted an immediate war with Great Britain. Dolley turned the White House into a place of hospitality, where politicians and their spouses could come together to have civil and pleasant conversations. The Executive Mansion achieved a happy medium between the stiff protocols of Washington and Adams and the casual male-dominated gatherings of Jefferson. James Madison won the 1812 election with 128 electoral votes to DeWitt Clinton’s 89.

Throughout his life, James maintained a close relationship with his father, James Madison Sr, who died in 1801. At age 50, James inherited the large plantation of Montpelier and other possessions, including his father’s numerous slaves. When James left office in 1817 he retired to Montpelier, which was not far from Jefferson’s Monticello. He occasionally became involved in public affairs, advising Andrew Jackson and other presidents. He also helped Jefferson establish the University of Virginia; after Jefferson’s death he was appointed as the second rector of the university, and retained the position as college chancellor for ten years until his death in 1836. He died of congestive heart failure at Montpelier on the morning of June 28, 1836; even though he had been frail throughout his life, he lived to the age of 85. Dolley lived another 13 years.

Throughout his life, James maintained a close relationship with his father, James Madison Sr, who died in 1801. At age 50, James inherited the large plantation of Montpelier and other possessions, including his father’s numerous slaves. When James left office in 1817 he retired to Montpelier, which was not far from Jefferson’s Monticello. He occasionally became involved in public affairs, advising Andrew Jackson and other presidents. He also helped Jefferson establish the University of Virginia; after Jefferson’s death he was appointed as the second rector of the university, and retained the position as college chancellor for ten years until his death in 1836. He died of congestive heart failure at Montpelier on the morning of June 28, 1836; even though he had been frail throughout his life, he lived to the age of 85. Dolley lived another 13 years.

Historian Garry Wills wrote, “Madison’s claim on our admiration does not rest on a perfect consistency, any more than it rests on his presidency. He has other virtues. … As a framer and defender of the Constitution, he had no peer. … The finest part of Madison’s performance as president was his concern for the preserving of the Constitution. … No man could do everything for the country—not even Washington. Madison did more than most, and did some things better than any. That was quite enough.”

» June 17th, 2024

#3. Jefferson, Thomas

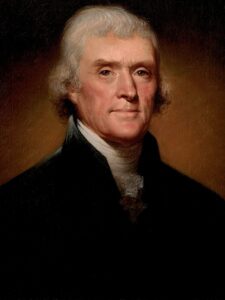

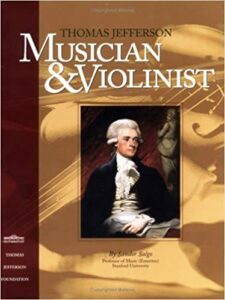

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas –Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was, to put it plainly, a Wonder Man. So far I’ve only found one thing he didn’t do, and that was “sit still.” He was a statesman, diplomat, and lawyer. He was an architect, farmer, and inventor. He collected books by the thousands and spoke as many languages as he had reason to learn. He was the second vice president of the United States, and the third president. He was governor of Virginia and founder of the University of Virginia. He was the principal author of the Declaration of Independence, he sent the Barbary Pirates skedaddling, and, oh yes, don’t forget – he doubled the size of the United States with the Louisiana Purchase. What can explain it? I think Thomas ate his Wheaties! Would Thomas come to your party? You betcha, and he would probably bring his violin along to entertain everyone. He and Patrick Henry used to hang together In Williamsburg doing just that.

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas –Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was, to put it plainly, a Wonder Man. So far I’ve only found one thing he didn’t do, and that was “sit still.” He was a statesman, diplomat, and lawyer. He was an architect, farmer, and inventor. He collected books by the thousands and spoke as many languages as he had reason to learn. He was the second vice president of the United States, and the third president. He was governor of Virginia and founder of the University of Virginia. He was the principal author of the Declaration of Independence, he sent the Barbary Pirates skedaddling, and, oh yes, don’t forget – he doubled the size of the United States with the Louisiana Purchase. What can explain it? I think Thomas ate his Wheaties! Would Thomas come to your party? You betcha, and he would probably bring his violin along to entertain everyone. He and Patrick Henry used to hang together In Williamsburg doing just that.

Thomas entered the College of William & Mary at age 16; he studied mathematics, metaphysics, and philosophy under professor William Small, who held Friday “dinner parties” where politics and philosophy were discussed. Although Thomas frittered away his first year dancing and squandering his money, he vowed in his second year to study “fifteen hours a day” and graduated in two years. He obtained a law license while working as a clerk under the tutelage of George Wythe, a noted law professor; and he read – he studied not only law and philosophy, he studied history, religion, ethics, science, and agriculture. Wythe was so impressed with Thomas he later bequeathed him his entire library.

Thomas entered the College of William & Mary at age 16; he studied mathematics, metaphysics, and philosophy under professor William Small, who held Friday “dinner parties” where politics and philosophy were discussed. Although Thomas frittered away his first year dancing and squandering his money, he vowed in his second year to study “fifteen hours a day” and graduated in two years. He obtained a law license while working as a clerk under the tutelage of George Wythe, a noted law professor; and he read – he studied not only law and philosophy, he studied history, religion, ethics, science, and agriculture. Wythe was so impressed with Thomas he later bequeathed him his entire library.

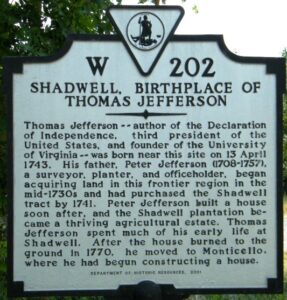

The adage “to make good old people you have to start them young” must have been in Peter Jefferson’s head when his son Thomas came into the world. Thomas was third of ten children, and the first son. Peter Jefferson had no formal education, but studied and improved himself; he inherited land, and managed plantations – his own in Eastern Virginia and that of the Shadwell family in the Piedmont (where Thomas was born). Peter and wife Jane offered a privileged life for their family; they frequently entertained, enjoyed classic books and music, and attended dances. They also hosted Native Americans who traveled through on official business in Williamsburg. Peter entered Thomas into an English school at age five; at age nine Thomas was sent to a school run by a Scottish Presbyterian minister, and began the study of Latin, Greek, and French. He also began studying the natural world, and riding horses. When Peter died in 1757, his estate was divided between his two sons Thomas and Randolph; Thomas inherited 5,000 acres of land – including Monticello – at the age of 14, and assumed full authority over his property at age 21.

The adage “to make good old people you have to start them young” must have been in Peter Jefferson’s head when his son Thomas came into the world. Thomas was third of ten children, and the first son. Peter Jefferson had no formal education, but studied and improved himself; he inherited land, and managed plantations – his own in Eastern Virginia and that of the Shadwell family in the Piedmont (where Thomas was born). Peter and wife Jane offered a privileged life for their family; they frequently entertained, enjoyed classic books and music, and attended dances. They also hosted Native Americans who traveled through on official business in Williamsburg. Peter entered Thomas into an English school at age five; at age nine Thomas was sent to a school run by a Scottish Presbyterian minister, and began the study of Latin, Greek, and French. He also began studying the natural world, and riding horses. When Peter died in 1757, his estate was divided between his two sons Thomas and Randolph; Thomas inherited 5,000 acres of land – including Monticello – at the age of 14, and assumed full authority over his property at age 21.

When you think about “expectations and reality” in the year 2020 – imagine heading off to college at 16, a wealthy landowner; imagine laughing it up and partying and spending all your money for a year; imagine wising up and buckling down and going on to become a Wonder Man. What would YOU do? There is a key statement Thomas made that I believe is an important factor for success. Five words, on record, that Thomas wrote to John Adams:

(Cell phone scrollers, note that!) Thomas amassed three different libraries in his lifetime. Those books left to him by George Wythe and the ones he inherited from his father were destroyed in a fire in 1770. Believe it or not, he had replenished his collection with 1,250 titles by 1773! By 1814, he owned 6,500 volumnes. After the British burned the White House, which contained the Library of Congress, on August 24, 1814, Thomas sold his books to the US Government to help jumpstart their collection and started his third personal library; when he died in 1826 it had grown to almost 2,000 volumes.

His Government Positions

- Member of Virginia House of Burgesses, 1769-74.

- Member of Continental Congress, 1775-76.

- Governor of Virginia, 1779-81.

- Member of Continental Congress, 1783-85.

- Minister to France, 1785-89.

- Secretary of State, 1790-93 (under Washington)

- Vice President, 1797-1801 (under J. Adams)

- 3rd President of the United States, 1801-1809

Keep the above dates in mind as we look at Thomas’ personal life. He married Martha Wayles in 1772 – she was 24, he was 29 and a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses. Martha’s first husband and first child had died; she brought considerable property to her marriage to Thomas, allowing him to greatly expand Monticello. The couple shared an interest in literature, horses, and music – she played the harpsichord and he the violin. Together they had six children but only two daughters lived to adulthood; and sadly, Martha died in 1882, ten years into the marriage. She did serve as First Lady of Virginia during Thomas’ governorship, but during the years he was Minister to France, Secretary of State, Vice President, and President – 1783-1809 –Thomas was a widower. His relationship with Sally Hemings, a slave, has been the subject of controversy for years; in 2012, the Smithsonian Institution and the Thomas Jefferson Foundation held a major exhibit at the National Museum of American History: Slavery at Jefferson’s Monticello: The Paradox of Liberty; it says that “evidence strongly supports the conclusion that [Thomas] Jefferson was the father of Sally Hemings’ six children.” It is a certainty that Martha Jefferson made Thomas promise never to remarry after her death, and he kept that promise.

Keep the above dates in mind as we look at Thomas’ personal life. He married Martha Wayles in 1772 – she was 24, he was 29 and a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses. Martha’s first husband and first child had died; she brought considerable property to her marriage to Thomas, allowing him to greatly expand Monticello. The couple shared an interest in literature, horses, and music – she played the harpsichord and he the violin. Together they had six children but only two daughters lived to adulthood; and sadly, Martha died in 1882, ten years into the marriage. She did serve as First Lady of Virginia during Thomas’ governorship, but during the years he was Minister to France, Secretary of State, Vice President, and President – 1783-1809 –Thomas was a widower. His relationship with Sally Hemings, a slave, has been the subject of controversy for years; in 2012, the Smithsonian Institution and the Thomas Jefferson Foundation held a major exhibit at the National Museum of American History: Slavery at Jefferson’s Monticello: The Paradox of Liberty; it says that “evidence strongly supports the conclusion that [Thomas] Jefferson was the father of Sally Hemings’ six children.” It is a certainty that Martha Jefferson made Thomas promise never to remarry after her death, and he kept that promise.

Inauguration One

Several interesting things marked Thomas Jefferson’s inauguration on March 4, 1801; the first time an inauguration was held in Washington, DC. The temperature was mild that day; an artillery company on Capitol Hill fired shots to welcome the daybreak. Thomas was staying at Conrad & McMunn’s boarding house on the south side of the Capitol. In contrast to his predecessors, he dressed plainly, arrived alone on horseback, and retired his own horse to the nearby stable. He’d given a copy of his speech to the National Intelligencer to be published right after delivery, another first; the theme was reconciliation after the bitterly partisan election. He gave his 1,721-word speech in the Capitol’s Senate chamber, and then took the oath of office, administered by Chief Justice John Marshal. In what would become standard practice, the Marine Band played for the first time at the inauguration. Outgoing President John Adams, distraught over his loss of the election as well as the death of his son Charles, was already on the morning stagecoach out of town.

Several interesting things marked Thomas Jefferson’s inauguration on March 4, 1801; the first time an inauguration was held in Washington, DC. The temperature was mild that day; an artillery company on Capitol Hill fired shots to welcome the daybreak. Thomas was staying at Conrad & McMunn’s boarding house on the south side of the Capitol. In contrast to his predecessors, he dressed plainly, arrived alone on horseback, and retired his own horse to the nearby stable. He’d given a copy of his speech to the National Intelligencer to be published right after delivery, another first; the theme was reconciliation after the bitterly partisan election. He gave his 1,721-word speech in the Capitol’s Senate chamber, and then took the oath of office, administered by Chief Justice John Marshal. In what would become standard practice, the Marine Band played for the first time at the inauguration. Outgoing President John Adams, distraught over his loss of the election as well as the death of his son Charles, was already on the morning stagecoach out of town.

Inauguration Two

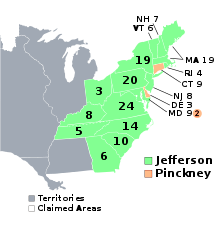

Thomas Jefferson rode to the Capitol on horseback on March 4, 1805, but much of Congress had already left after the body had adjourned following Burr’s farewell address before the Senate a couple of days earlier. The inaugural ceremony was modest; Thomas spoke softly and quietly and provided copies of his inaugural address. In the speech, he addressed the recent acquisition of Louisiana, the Federalists’ diminishing influence, and the need for freedom of the press, though he also criticized recent press attacks against him. His successful first term had brought him back into office in a landslide vote of 162 to 14; achievements were a strong economy, lower taxes, and the Louisiana Purchase.

Thomas Jefferson rode to the Capitol on horseback on March 4, 1805, but much of Congress had already left after the body had adjourned following Burr’s farewell address before the Senate a couple of days earlier. The inaugural ceremony was modest; Thomas spoke softly and quietly and provided copies of his inaugural address. In the speech, he addressed the recent acquisition of Louisiana, the Federalists’ diminishing influence, and the need for freedom of the press, though he also criticized recent press attacks against him. His successful first term had brought him back into office in a landslide vote of 162 to 14; achievements were a strong economy, lower taxes, and the Louisiana Purchase.

Voter participation grew during Jefferson’s presidency, increasing to “unimaginable levels” compared to the Federalist Era, with turnout of about 67,000 in 1800 rising to about 143,000 in 1804.

And Then

After retiring from public office, Thomas Jefferson founded the University of Virginia. He envisioned a university free of church influences where students could specialize in many new areas not offered at other colleges. He believed that education was necessary for a stable society, and that publicly funded schools should be accessible to students from all social strata. He organized the state legislative campaign for the University’s charter and, with the assistance of Edmund Bacon, purchased the location. He was the principal designer of the buildings, planned the curriculum, and served as the first rector. The university had a library rather than a church at its center, emphasizing its secular nature—a controversial aspect at the time. He bequeathed most of his library to the university upon his death – Independence Day, July 4, 1826.

After retiring from public office, Thomas Jefferson founded the University of Virginia. He envisioned a university free of church influences where students could specialize in many new areas not offered at other colleges. He believed that education was necessary for a stable society, and that publicly funded schools should be accessible to students from all social strata. He organized the state legislative campaign for the University’s charter and, with the assistance of Edmund Bacon, purchased the location. He was the principal designer of the buildings, planned the curriculum, and served as the first rector. The university had a library rather than a church at its center, emphasizing its secular nature—a controversial aspect at the time. He bequeathed most of his library to the university upon his death – Independence Day, July 4, 1826.

My personal favorite of Thomas Jefferson’s thousands of accomplishments, (besides that of being such an avid book collector) is the Louisiana Purchase. I live in Arkansas, near the “Louisiana Purchase Marker” which makes me a part of “living history” in a touchable form; I also lived near the Ouachita River, where the famous Dunbar-Hunter Expedition passed through in 1804-1805. Thomas sent out four expeditions in all: the Freeman-Custis (1806) on  the Red River, the Zebulon Pike Expedition (1806-1807) into the Rocky Mountains; and of course the Lewis & Clark Expedition (1803-1806) that made it to the Pacific Ocean. And there was all that tinkering he did – he invented a revolving bookstand (natural for a book lover), the swivel chair, and many other practical and useful devices. In addition to all the beautiful buildings at Monticello and the University of Virginia, he also designed one of the prettiest state capitols – Richmond, Virginia.