» posted on Tuesday, June 18th, 2024 by Linda Lou Burton

#4. Madison, James

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – James Madison (March 16, 1751 – June 28, 1836) was the fourth president of the United States (1809 to 1817) and the third Virginia planter to be elected. But James has a very special distinction nobody else comes close to — he was the SMALLEST president ever. No kidding, he was 5’4″ and weighed barely 100 pounds. In addition, he was very soft spoken. Despite what might be considered weaknesses, he was a close advisor to George Washington, and the main force behind the ratification of the Bill of Rights. He wound up being remembered as the “Father of the Constitution”! But even more startling for such a diminutive fellow, he is the only president who started a war, and then, with no military experience whatsoever, rode his horse onto the battlefield under fire! Would you want this guy at your party? You would if he brought Dolley. His pretty wife Dolley knew how to get people together, and get them talking. She was a great hostess; the first real “first lady” in the White House. She was so charming that she sometimes served as hostess for President Thomas Jefferson (remember, he was a widower), before she lived in the White House herself. Dolley loved the White House and really made the history books for something she did on August 24, 1814.

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – James Madison (March 16, 1751 – June 28, 1836) was the fourth president of the United States (1809 to 1817) and the third Virginia planter to be elected. But James has a very special distinction nobody else comes close to — he was the SMALLEST president ever. No kidding, he was 5’4″ and weighed barely 100 pounds. In addition, he was very soft spoken. Despite what might be considered weaknesses, he was a close advisor to George Washington, and the main force behind the ratification of the Bill of Rights. He wound up being remembered as the “Father of the Constitution”! But even more startling for such a diminutive fellow, he is the only president who started a war, and then, with no military experience whatsoever, rode his horse onto the battlefield under fire! Would you want this guy at your party? You would if he brought Dolley. His pretty wife Dolley knew how to get people together, and get them talking. She was a great hostess; the first real “first lady” in the White House. She was so charming that she sometimes served as hostess for President Thomas Jefferson (remember, he was a widower), before she lived in the White House herself. Dolley loved the White House and really made the history books for something she did on August 24, 1814.

A Wild Story

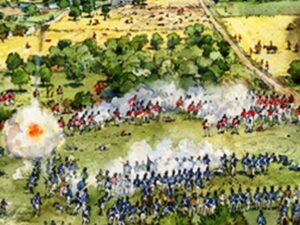

Another war with those pesky British was going on; often called the Second War of Independence but officially the War of 1812. Around noon that day about 4,500 British marched within sight of Bladensburg, Maryland, nine miles NE of Washington. James Madison galloped onto the scene and proceeded to ride across a ridge overlooking the battlefield. According to the White House Historical Society and Dolley’s personal letters, James Madison had left the White House on August 22 to meet with his generals on the battlefield; the British troops were dangerously close to the capital. Before leaving, he asked Dolley if she had the “courage or firmness” to wait for his intended return the next day. He asked her to gather important state papers and be prepared to abandon the White House at any moment. Dolley started making lists and getting organized; she also

Another war with those pesky British was going on; often called the Second War of Independence but officially the War of 1812. Around noon that day about 4,500 British marched within sight of Bladensburg, Maryland, nine miles NE of Washington. James Madison galloped onto the scene and proceeded to ride across a ridge overlooking the battlefield. According to the White House Historical Society and Dolley’s personal letters, James Madison had left the White House on August 22 to meet with his generals on the battlefield; the British troops were dangerously close to the capital. Before leaving, he asked Dolley if she had the “courage or firmness” to wait for his intended return the next day. He asked her to gather important state papers and be prepared to abandon the White House at any moment. Dolley started making lists and getting organized; she also  prepared a “welcome back” dinner for James and the officers to enjoy on his return. I won’t go into all the shooting and shouting that happened on the battlefield that day, but the Americans were defeated, and the British marched into Washington and set it on fire. Dolley’s time for getting safely across the Potomac into Virginia was shortened to nearly nothing, but her determination kept her on track; the huge Stuart portrait of George Washington was cut from its frame (too many screws to be able to detach it from the wall); the canvas was rolled and saved. The White House emptied; the British entered, found the fine china, and gobbled up the nice dinner Dolley had prepared. After a bit of looting they set fire to the place.

prepared a “welcome back” dinner for James and the officers to enjoy on his return. I won’t go into all the shooting and shouting that happened on the battlefield that day, but the Americans were defeated, and the British marched into Washington and set it on fire. Dolley’s time for getting safely across the Potomac into Virginia was shortened to nearly nothing, but her determination kept her on track; the huge Stuart portrait of George Washington was cut from its frame (too many screws to be able to detach it from the wall); the canvas was rolled and saved. The White House emptied; the British entered, found the fine china, and gobbled up the nice dinner Dolley had prepared. After a bit of looting they set fire to the place.

The Americans’ defeat at Bladensburg was embarrassing, but that wasn’t the worst of it. Raiding parties set fire to the Capitol, the chambers of the Senate and House of Representatives, the Treasury Department, and the War Office, as well as the White House. The city was blazing. Dolley found her husband at their predetermined meeting place as a raging thunderstorm blew into the city. And that storm, actually defined as a hurricane, put out the fires. It also spun off a tornado that set down on Constitution Avenue and lifted two cannons before dropping them several yards away, killing some British troops and American civilians. The British returned to their ships, many of which were damaged. The rains sizzled and cracked the charred walls of the White House; the storm even destroyed some structures that had not been burned. Karma had a big night. An encounter was noted between a British officer and a female resident of Washington. She called out to him, “This is a special interposition of Providence to drive our enemies from our city,” to

The Americans’ defeat at Bladensburg was embarrassing, but that wasn’t the worst of it. Raiding parties set fire to the Capitol, the chambers of the Senate and House of Representatives, the Treasury Department, and the War Office, as well as the White House. The city was blazing. Dolley found her husband at their predetermined meeting place as a raging thunderstorm blew into the city. And that storm, actually defined as a hurricane, put out the fires. It also spun off a tornado that set down on Constitution Avenue and lifted two cannons before dropping them several yards away, killing some British troops and American civilians. The British returned to their ships, many of which were damaged. The rains sizzled and cracked the charred walls of the White House; the storm even destroyed some structures that had not been burned. Karma had a big night. An encounter was noted between a British officer and a female resident of Washington. She called out to him, “This is a special interposition of Providence to drive our enemies from our city,” to  which he replied, “Not so, Madam, it is rather to aid your enemies in the destruction of your city.” The Smithsonian reports there have only been seven other tornadoes recorded in Washington, DC in the 206 years since.

which he replied, “Not so, Madam, it is rather to aid your enemies in the destruction of your city.” The Smithsonian reports there have only been seven other tornadoes recorded in Washington, DC in the 206 years since.

The British occupation of Washington lasted only about 26 hours, and on December 24, 1814, the Treaty of Ghent formally ended the War of 1812. Although James and Dolley were able to return to Washington by September, they never again lived in the White House.

Enough About War

Let’s lighten the tone! What about James’ early days? He was born March 16, 1751 at Belle Grove Plantation near Port Conway, Virginia; the Madison family had lived in Virginia since the mid-1600s. James was the firstborn child of James Madison Sr, and Nelly Conway Madison; eleven more children followed, though only six lived to adulthood. James Sr was the largest landowner in the area –5,000 acres and 100 slaves. In the early 1760s they built “Montpelier,” which ultimately was James’ final resting place. Though James was small, he was a naturally curious and studious child; his education began at home under his mother; then he studied with a distinguished Scottish teacher – mathematics, geography, classical languages, philosophy.  Instead of moving on to William & Mary as most prominent Virginians did, he went north to the College of New Jersey (now Princeton); it was thought the climate would be better for his health than the humidity of coastal Williamsburg. He graduated in 1771 at the age of 20; but unsure about a vocation, he stayed on and kept studying – the college’s first “graduate student.” Although he studied law, he never practiced; but politics seemed an inevitable choice, as he always took an interest in how governments functioned. He started local, as a member of the Orange County Committee of Safety in 1774. From there it grew.

Instead of moving on to William & Mary as most prominent Virginians did, he went north to the College of New Jersey (now Princeton); it was thought the climate would be better for his health than the humidity of coastal Williamsburg. He graduated in 1771 at the age of 20; but unsure about a vocation, he stayed on and kept studying – the college’s first “graduate student.” Although he studied law, he never practiced; but politics seemed an inevitable choice, as he always took an interest in how governments functioned. He started local, as a member of the Orange County Committee of Safety in 1774. From there it grew.

Other Government Positions

- Member of Virginia Constitutional Convention, 1776

- Member of Continental Congress, 1780-83

- Member of Virginia Legislature, 1784-86

- Member of Constitutional Convention, 1787

- Member of U.S. House of Representatives, 1789-97

- Secretary of State, 1801-09 (under Jefferson)

- Fourth President of the United States, 1809-1817

The Family Man

Something besides politics caught James attention in 1794, when he was introduced to a young widow named Dolley Payne Todd (1768-1849) by a mutual acquaintance, Aaron Burr. She had recently lost her husband and youngest child in a yellow fever epidemic. James and Dolley were married within the year – he was 43, she was 26. James enjoyed a strong relationship with his wife; she became his political partner; he adopted her son John Payne Todd, who was two when they married.

Something besides politics caught James attention in 1794, when he was introduced to a young widow named Dolley Payne Todd (1768-1849) by a mutual acquaintance, Aaron Burr. She had recently lost her husband and youngest child in a yellow fever epidemic. James and Dolley were married within the year – he was 43, she was 26. James enjoyed a strong relationship with his wife; she became his political partner; he adopted her son John Payne Todd, who was two when they married.

When friend and colleague Thomas Jefferson named James Secretary of State in 1801, the Madisons moved to Washington; when Jefferson’s time in the White House came to a close, James Madison won the 1808 election with 122 electoral votes to Charles Pinckney’s 47. After the Madisons moved into the White House in 1809, both Dolley and James began working in their own unique ways to bring about compromises in a Congress that was divided. James attempted to balance the demands of Henry Clay’s War Hawks, who wanted an immediate war with Great Britain. Dolley turned the White House into a place of hospitality, where politicians and their spouses could come together to have civil and pleasant conversations. The Executive Mansion achieved a happy medium between the stiff protocols of Washington and Adams and the casual male-dominated gatherings of Jefferson. James Madison won the 1812 election with 128 electoral votes to DeWitt Clinton’s 89.

Throughout his life, James maintained a close relationship with his father, James Madison Sr, who died in 1801. At age 50, James inherited the large plantation of Montpelier and other possessions, including his father’s numerous slaves. When James left office in 1817 he retired to Montpelier, which was not far from Jefferson’s Monticello. He occasionally became involved in public affairs, advising Andrew Jackson and other presidents. He also helped Jefferson establish the University of Virginia; after Jefferson’s death he was appointed as the second rector of the university, and retained the position as college chancellor for ten years until his death in 1836. He died of congestive heart failure at Montpelier on the morning of June 28, 1836; even though he had been frail throughout his life, he lived to the age of 85. Dolley lived another 13 years.

Throughout his life, James maintained a close relationship with his father, James Madison Sr, who died in 1801. At age 50, James inherited the large plantation of Montpelier and other possessions, including his father’s numerous slaves. When James left office in 1817 he retired to Montpelier, which was not far from Jefferson’s Monticello. He occasionally became involved in public affairs, advising Andrew Jackson and other presidents. He also helped Jefferson establish the University of Virginia; after Jefferson’s death he was appointed as the second rector of the university, and retained the position as college chancellor for ten years until his death in 1836. He died of congestive heart failure at Montpelier on the morning of June 28, 1836; even though he had been frail throughout his life, he lived to the age of 85. Dolley lived another 13 years.

Historian Garry Wills wrote, “Madison’s claim on our admiration does not rest on a perfect consistency, any more than it rests on his presidency. He has other virtues. … As a framer and defender of the Constitution, he had no peer. … The finest part of Madison’s performance as president was his concern for the preserving of the Constitution. … No man could do everything for the country—not even Washington. Madison did more than most, and did some things better than any. That was quite enough.”