Archive for September 26th, 2020

» posted on Saturday, September 26th, 2020 by Linda Lou Burton

#7. Jackson, Andrew

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States (1829 to 1837), and a man of many contradictions. The first person to write his biography after his death, James Parton, summed it like this: “Andrew Jackson…was a patriot and a traitor. He was one of the greatest generals, and wholly ignorant of the art of war. A brilliant writer, elegant, eloquent, without being able to compose a correct sentence or spell words of four syllables. The first of statesmen, he never devised, he never framed, a measure. He was the most candid of men, and was capable of the most profound dissimulation. A most law-defying law-obeying citizen. A stickler for discipline, he never hesitated to disobey his superior. A democratic autocrat. An urbane savage. An atrocious saint.” Would you want this man at your party? I would; I’d like to hear what he thinks of the Electoral College system today. Some outcomes have even been worse than what happened to him back in 1824. But it might be a tricky evening – he shot a lot of people, and, he got shot, and shot AT, many times in his 78 years. When he died, he still had bullets rattling around in his chest. He had scars on his face and in his heart; and he had grudges going way, way back. But there are also stories of great passion, and tenderness.

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States (1829 to 1837), and a man of many contradictions. The first person to write his biography after his death, James Parton, summed it like this: “Andrew Jackson…was a patriot and a traitor. He was one of the greatest generals, and wholly ignorant of the art of war. A brilliant writer, elegant, eloquent, without being able to compose a correct sentence or spell words of four syllables. The first of statesmen, he never devised, he never framed, a measure. He was the most candid of men, and was capable of the most profound dissimulation. A most law-defying law-obeying citizen. A stickler for discipline, he never hesitated to disobey his superior. A democratic autocrat. An urbane savage. An atrocious saint.” Would you want this man at your party? I would; I’d like to hear what he thinks of the Electoral College system today. Some outcomes have even been worse than what happened to him back in 1824. But it might be a tricky evening – he shot a lot of people, and, he got shot, and shot AT, many times in his 78 years. When he died, he still had bullets rattling around in his chest. He had scars on his face and in his heart; and he had grudges going way, way back. But there are also stories of great passion, and tenderness.

What happened to Andrew in his early life? It pretty much sucked; a Charles Dickenson-Oliver Twist tear-jerker if you ask me. This red-headed blue-eyed Irishman was in defense mode from his first breath, just trying to survive.

Stage One

Andrew Jackson and Elizabeth Hutchinson immigrated from Ireland in 1765; they landed in Philadelphia and headed south through the Appalachian Mountains to a Scots-Irish community on the border between North and South Carolina. They brought two children with them, Hugh was two, Robert was a year old. Three weeks before Andrew was born in March of 1767, his father was killed in a logging accident. Elizabeth and her three little boys lived with relatives in the community for a while; the boys had some schooling from a nearby priest. Contradictions began early on – Andrew was a bully, but he also took weaker kids under his wing in kindness. Andrew was nine when the Revolutionary War began; his brother Hugh was  killed in battle in 1779. Elizabeth encouraged Robert and Andrew to attend local militia drills; they soon became couriers; but were captured by the British in April 1781 (Andrew was 14). They were not good POW’s – Andrew refused to clean an officer’s boots; the officer’s sword quickly slashed his face and hand; it left Andrew with scars and an intense hatred for the British. The story doesn’t get prettier; both boys contracted smallpox and almost starved in captivity. Elizabeth somehow managed to secure their release; the three began walking the 40 miles back home when a torrential downpour began. Two days after returning home, Robert was dead and Andrew terribly ill. After nursing Andrew back to health, Elizabeth volunteered to nurse American prisoners of war on board two British ships in the Charleston harbor, where there had been an outbreak of cholera. She died from the disease in November and is buried in an unmarked grave. By the end of 1781, Andrew was an orphan. Summary of his 14th year – he suffered captivity by the British, near starvation, the disease of smallpox, and the loss of two brothers and his mother. The scars from his smallpox and that British sword stayed with him forever. So did his hatred of the British. How would you feel after such a year? And what did Andrew do next?

killed in battle in 1779. Elizabeth encouraged Robert and Andrew to attend local militia drills; they soon became couriers; but were captured by the British in April 1781 (Andrew was 14). They were not good POW’s – Andrew refused to clean an officer’s boots; the officer’s sword quickly slashed his face and hand; it left Andrew with scars and an intense hatred for the British. The story doesn’t get prettier; both boys contracted smallpox and almost starved in captivity. Elizabeth somehow managed to secure their release; the three began walking the 40 miles back home when a torrential downpour began. Two days after returning home, Robert was dead and Andrew terribly ill. After nursing Andrew back to health, Elizabeth volunteered to nurse American prisoners of war on board two British ships in the Charleston harbor, where there had been an outbreak of cholera. She died from the disease in November and is buried in an unmarked grave. By the end of 1781, Andrew was an orphan. Summary of his 14th year – he suffered captivity by the British, near starvation, the disease of smallpox, and the loss of two brothers and his mother. The scars from his smallpox and that British sword stayed with him forever. So did his hatred of the British. How would you feel after such a year? And what did Andrew do next?

On To Rachel, and Orphans

Andrew made do. He boarded with various people, went to a local school, tried saddle making, and studied with enough lawyers to be admitted to the bar in North Carolina in 1787, at the age of 20. Then Andrew headed west; he got a job as a prosecutor in western North Carolina; he bought his first slave, fought his first duel, and moved on to Nashville, a small frontier town, in 1788. That’s where he met Rachel. Rachel Donelson Robards (1767-1828) was married at the time; an unhappy marriage. The story goes that she divorced Captain Robards, and married Andrew in 1791 – they were both 24. It seems Rachel’s divorce wasn’t final however and she and Andrew were in a bigamous relationship; they did a redo and married for the second time in 1794. Evidence shows that Rachel was living with Andrew before the petition for divorce was ever made; a fact that was raked over the coals during Andrew’s presidential campaign. His love for Rachel is a “once is enough” romance, with many happy days but a tragic end. Rachel often struggled while Andrew was away, but she began experiencing significant physical stress during the election season. She died of a heart attack on December 22, 1828, 10 weeks before her husband took office as president. Andrew literally had to be pulled from her side so the undertaker could prepare the body. Believing that the abuse from John Quincy Adams’ supporters hastened her death, Andrew swore at her funeral, “May God Almighty forgive her murderers. I never can.”

Andrew made do. He boarded with various people, went to a local school, tried saddle making, and studied with enough lawyers to be admitted to the bar in North Carolina in 1787, at the age of 20. Then Andrew headed west; he got a job as a prosecutor in western North Carolina; he bought his first slave, fought his first duel, and moved on to Nashville, a small frontier town, in 1788. That’s where he met Rachel. Rachel Donelson Robards (1767-1828) was married at the time; an unhappy marriage. The story goes that she divorced Captain Robards, and married Andrew in 1791 – they were both 24. It seems Rachel’s divorce wasn’t final however and she and Andrew were in a bigamous relationship; they did a redo and married for the second time in 1794. Evidence shows that Rachel was living with Andrew before the petition for divorce was ever made; a fact that was raked over the coals during Andrew’s presidential campaign. His love for Rachel is a “once is enough” romance, with many happy days but a tragic end. Rachel often struggled while Andrew was away, but she began experiencing significant physical stress during the election season. She died of a heart attack on December 22, 1828, 10 weeks before her husband took office as president. Andrew literally had to be pulled from her side so the undertaker could prepare the body. Believing that the abuse from John Quincy Adams’ supporters hastened her death, Andrew swore at her funeral, “May God Almighty forgive her murderers. I never can.”

Andrew and Rachel never had children together but adopted, or cared for “a lot of kids” in their Nashville home, The Hermitage. In 1808, they took in one of the infant twins of Rachel’s brother Severn Donelson, and raised him as their own. They named him Andrew

Andrew and Rachel never had children together but adopted, or cared for “a lot of kids” in their Nashville home, The Hermitage. In 1808, they took in one of the infant twins of Rachel’s brother Severn Donelson, and raised him as their own. They named him Andrew  Jackson Jr. (1808-1865). When Rachel’s brother Samuel Donelson died in 1804 they cared for his three sons — John Samuel, Andrew Jackson, and Daniel. When Andrew found a Native American child on the battlefield with his dead mother in 1813, he brought him to the Hermitage, named him Lyncoya, and raised and educated him along with Andrew Jr. Andrew Jackson Hutchings, grandson of Rachel’s sister, lost both parents when he was five; he too was brought to the Hermitage and attended school with Andrew Jr and Lyncoya. Quite a legacy for one who was orphaned at an early age himself.

Jackson Jr. (1808-1865). When Rachel’s brother Samuel Donelson died in 1804 they cared for his three sons — John Samuel, Andrew Jackson, and Daniel. When Andrew found a Native American child on the battlefield with his dead mother in 1813, he brought him to the Hermitage, named him Lyncoya, and raised and educated him along with Andrew Jr. Andrew Jackson Hutchings, grandson of Rachel’s sister, lost both parents when he was five; he too was brought to the Hermitage and attended school with Andrew Jr and Lyncoya. Quite a legacy for one who was orphaned at an early age himself.

The Battles

This tender man who cared for so many children in need also fought in four different wars – the Revolutionary War, the Creek War, the War of 1812, and the First Seminole War. I’ll let you look those up yourself to read about his fierceness, campaign strategies, and tough leadership skills; there is much written about him as “War Hero.” He, like George Washington and James Monroe, got back up and kept fighting, no matter how many times he was down. He earned the nickname “Old Hickory” because he was a strict and bold military officer, unbending as a tree, and tough as wood.

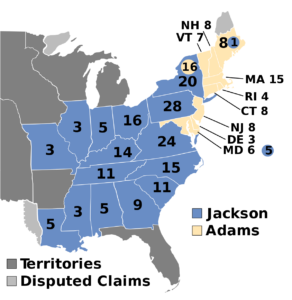

He ran for president in 1824, winning the most popular and electoral votes. But that was a battle he LOST. Since no candidate won an electoral majority, the House of Representatives elected John Quincy Adams in a contingent election. In the years ahead, Andrew Jackson repeatedly called for the abolition of the Electoral College, recommending “giving the election of President and Vice-President to the people.”

He ran for president in 1824, winning the most popular and electoral votes. But that was a battle he LOST. Since no candidate won an electoral majority, the House of Representatives elected John Quincy Adams in a contingent election. In the years ahead, Andrew Jackson repeatedly called for the abolition of the Electoral College, recommending “giving the election of President and Vice-President to the people.”

The Tennessee legislature didn’t waste any time in nominating Andrew for president again – they did it more than three years before the 1828 election, the earliest nomination in presidential history. The campaign was personal, and mean; the candidates didn’t campaign but the press stayed on it, calling Andrew Jackson a slave trader and a cannibal (eating the bodies of Indians killed in battle); they called his mother a prostitute and his father a mulatto; and of course, there was that “bigamy” issue about Rachel. Karma again did what Karma does – Andrew Jackson received 178 electoral votes to John Quincy Adams’ 83. And for the second time, an outgoing president did not attend the new president’s inauguration.

The Tennessee legislature didn’t waste any time in nominating Andrew for president again – they did it more than three years before the 1828 election, the earliest nomination in presidential history. The campaign was personal, and mean; the candidates didn’t campaign but the press stayed on it, calling Andrew Jackson a slave trader and a cannibal (eating the bodies of Indians killed in battle); they called his mother a prostitute and his father a mulatto; and of course, there was that “bigamy” issue about Rachel. Karma again did what Karma does – Andrew Jackson received 178 electoral votes to John Quincy Adams’ 83. And for the second time, an outgoing president did not attend the new president’s inauguration.

Neither did Andrew’s wife of course. On March 4, 1829, ten weeks after her Christmas Eve  funeral at the Hermitage, Andrew Jackson became the first president-elect to take the oath of office on the East Portico of the US Capitol. At the end of the ceremony, he invited the public to the White House for a party. This “common man of the people” spent his first day as president surrounded by thousands of people living it up in the White House; the staff was overwhelmed and fixtures and furnishings were damaged.

funeral at the Hermitage, Andrew Jackson became the first president-elect to take the oath of office on the East Portico of the US Capitol. At the end of the ceremony, he invited the public to the White House for a party. This “common man of the people” spent his first day as president surrounded by thousands of people living it up in the White House; the staff was overwhelmed and fixtures and furnishings were damaged.

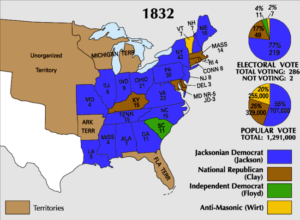

The second inauguration of Andrew Jackson took place in the House Chamber of the US Capitol on March 4, 1833. It was held inside because the temperature was 29 degrees, there was snow on the ground, and Andrew’s health was poor. His private secretary, Andrew  Jackson Donelson, stood on his right during the swearing in. Remember him? One of Rachel’s nephews that he raised. Martin Van Buren, the new vice president, stood to the left. No mob parties at the White House this time; but two inaugural balls. That evening there were 50-gun salutes at 9 PM and at midnight. Andrew won this time with 219 electoral votes to Clay’s 49. The country had grown to 24 states, and at that moment in time, was not in conflict with any nation.

Jackson Donelson, stood on his right during the swearing in. Remember him? One of Rachel’s nephews that he raised. Martin Van Buren, the new vice president, stood to the left. No mob parties at the White House this time; but two inaugural balls. That evening there were 50-gun salutes at 9 PM and at midnight. Andrew won this time with 219 electoral votes to Clay’s 49. The country had grown to 24 states, and at that moment in time, was not in conflict with any nation.

Andrew retired to the Hermitage in 1837, and though in poor health, he remained influential in national and state politics. On June 8, 1845, surrounded by family and friends, he died of heart failure at the age of 78. Historian Charles Grier Sellers wrote about him: “There has never been universal agreement on Jackson’s legacy, for his opponents have ever been his most bitter enemies, and his friends almost his worshippers.”

His Government Positions

- Member of U.S. House of Representatives, 1796-97

- United States Senator, 1797-98

- Justice on Tennessee Supreme Court, 1798-1804

- Governor of the Florida Territory, 1821

- United States Senator, 1823-25

- Seventh President of the United States, 1829-1837

My maternal grandfather, born in the late 1800s, was named after Andrew Jackson. My grandfather also was orphaned at an early age – his mother died when he was four; his father when he was fourteen. I find him on the US Census at age 16, boarding with one of his brothers at the home of a man who owned a sawmill.

Isn’t that ironic?