Archive for September 20th, 2020

» posted on Sunday, September 20th, 2020 by Linda Lou Burton

#1. Washington, George

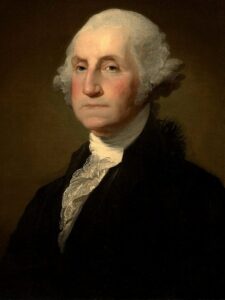

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – George Washington (February 22, 1732 – December 14, 1799) was red headed. Does that surprise you? The image in my mind when I hear the name “George Washington” is of a rather somber fellow with powdered-white hair. After all, that’s the picture hanging in almost every classroom in the United States. In truth, this red-headed fellow had sparkling grey-blue eyes, was more than six feet tall, and was known for his great strength. If George were alive today, you’d want him at your parties. He was a bit reserved, but had a strong presence and was well respected. He was rugged; he loved horses and collected thoroughbreds. He loved to hunt – foxes, deer, ducks and other game. But George was also an

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – George Washington (February 22, 1732 – December 14, 1799) was red headed. Does that surprise you? The image in my mind when I hear the name “George Washington” is of a rather somber fellow with powdered-white hair. After all, that’s the picture hanging in almost every classroom in the United States. In truth, this red-headed fellow had sparkling grey-blue eyes, was more than six feet tall, and was known for his great strength. If George were alive today, you’d want him at your parties. He was a bit reserved, but had a strong presence and was well respected. He was rugged; he loved horses and collected thoroughbreds. He loved to hunt – foxes, deer, ducks and other game. But George was also an  excellent dancer and loved the theater. He drank in moderation but opposed excessive drinking, smoking, gambling, and profanity.

excellent dancer and loved the theater. He drank in moderation but opposed excessive drinking, smoking, gambling, and profanity.

George was a good husband; when he married widow Martha Dandridge Custis in 1759 – he was 26, she was 27 – he assumed the role of husband, father to Martha’s two children Patsy and  Jacky, and manager of Martha’s considerable estate. When Patsy died suddenly, George canceled all business dealings to stay by Martha’s side for three months. When Jacky died at the age of 26, George and Martha took in their grandchildren Nelly and Washy (George Washington Custis) and raised them. They never had children together, to the regret of both.

Jacky, and manager of Martha’s considerable estate. When Patsy died suddenly, George canceled all business dealings to stay by Martha’s side for three months. When Jacky died at the age of 26, George and Martha took in their grandchildren Nelly and Washy (George Washington Custis) and raised them. They never had children together, to the regret of both.

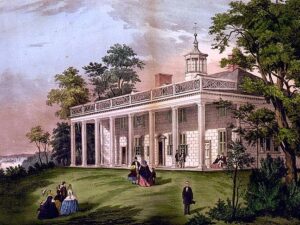

“Second shift” parenting was common at this point in history – one parent died, the other remarried, and children often grew up with half-siblings and a step-parent. Fortunes were gained through inheritance; land was the most desirable of assets. When George was born as the first child of Augustine and Mary Ball Washington in 1732, he had three older half-siblings from Augustine’s marriage to Jane Butler. Lawrence was 14, Augustine Jr was 12, and Jane was 10. George was just a year old when sister Betty was born; then Samuel, John Augustine, Charles, and Mildred by the time George was 7 years old. Augustine Washington was a prominent public figure; his own father had made a fortune in land speculation. When Augustine died in 1743, George, at the age of 11, inherited 10 slaves and Ferry Farm, near Fredericksburg, Virginia. Lawrence, age 25, inherited the land that became Mount Vernon.

George’s mother Mary never remarried, but chose to manage her land and raise her children on her own. She was unable to send George to school in England, where the older boys were educated; but George did learn mathematics, trigonometry, and land surveying and became a talented draftsman and map maker. George often visited Mount Vernon, and Belvoir, a plantation that belonged to Lawrence’s father-in-law William Fairfax. Fairfax became  George’s patron; after George received a surveyor’s license from William & Mary College, Fairfax appointed him Surveyor of Culpepper County. George became familiar with the frontier region and by 1752, at the age of 20, had bought 1,500 acres in the Valley.

George’s patron; after George received a surveyor’s license from William & Mary College, Fairfax appointed him Surveyor of Culpepper County. George became familiar with the frontier region and by 1752, at the age of 20, had bought 1,500 acres in the Valley.

That’s how a career begins and a fortune builds; when Lawrence died George leased Mount Vernon from his widow; when she died he inherited the property. When George and Martha married in 1759 she and her children moved to Mount Vernon; it is where George died in 1799, and Martha in 1802; both are buried there. By occupation, George was a planter; he grew tobacco, wheat, and corn. He was counted among the social and political elite of Virginia; inviting guests to Mount Vernon; enjoying leisure time; and eventually becoming politically active.

Lest George’s life sound too peaceful and laid back, there were a few other things going on. For instance, George had an unbelievable military career. He fought in a lot of battles! He had two horses shot out from under him in the same battle! He had bullet holes in his coat and hat! He was a fighter, and he never, ever gave up! George was a Colonel in the Colonial forces; General and Commander in Chief of the Continental Army, and a Lieutenant General in the US Army. We’re familiar with the famous Emanuel Leutze painting of Washington Crossing The Delaware; it would take a gallery to house portraits of all the battles he fought, in all the different campaigns. To name a few:

Lest George’s life sound too peaceful and laid back, there were a few other things going on. For instance, George had an unbelievable military career. He fought in a lot of battles! He had two horses shot out from under him in the same battle! He had bullet holes in his coat and hat! He was a fighter, and he never, ever gave up! George was a Colonel in the Colonial forces; General and Commander in Chief of the Continental Army, and a Lieutenant General in the US Army. We’re familiar with the famous Emanuel Leutze painting of Washington Crossing The Delaware; it would take a gallery to house portraits of all the battles he fought, in all the different campaigns. To name a few:

French and Indian War (1754-1763; George was 22-31): Battle of Jumonville Glen – Battle of Fort Necessity – Braddock Expedition – Battle of the Monongahela – Forbes Expedition

American Revolutionary War (1775-1783: George was 43-51): Boston campaign – New York and New Jersey campaign – Philadelphia campaign – Yorktown campaign

His military service took place before his marriage to Martha and during; when the Treaty of Paris was signed in Annapolis in 1783, and Great Britain officially recognized the independence of the United States, George resigned as Commander in Chief of the Continental Army with plans to retire to Mount Vernon, and a peaceful life with Martha.

His military service took place before his marriage to Martha and during; when the Treaty of Paris was signed in Annapolis in 1783, and Great Britain officially recognized the independence of the United States, George resigned as Commander in Chief of the Continental Army with plans to retire to Mount Vernon, and a peaceful life with Martha.

It didn’t turn out that way. Before he returned to private life, he called for a strong union, sending a letter to all states saying that the Articles of Confederation were no more than a “rope of sand” linking the states. He believed the nation was on the verge of anarchy and confusion, and that a national constitution unifying the states under a strong central government was essential. You know your history – a Constitutional Convention, delegates from all states convened in Philadelphia, a new constitution was called for; continued discussion and disagreement until finally, on February 4, 1789, the state electors voted for a president. There was no quorum present to count the votes until April 5; the next day the votes were tallied and Congressional Secretary Charles Thomson was sent to Mount Vernon to tell George he had won the majority of every state’s electoral votes. John Adams received the second highest vote count, so would be vice-president.

Just think – no campaigning, no national TV debating; and most interesting of all – no desire to BE president of this newly emerging entity called the “United States.” George admitted to “anxious and painful sensations” about leaving Mount Vernon, but departed for New York City on April 16 to be inaugurated. He took the oath of office at Federal Hall in New York City on April 30, 1789 at the age of 57. A crowd of 10,000 gathered; there was a parade complete with marching band, foreign dignitaries, and statesmen; the militia fired a 13-gun salute. George read a speech in the Senate Chamber, asking that “the Almighty Being who rules over the universe…consecrate the liberties and happiness of the people of the United States.”

These essays are not about the presidency, but rather the road TO the presidency, and the type of person who won the attention of the electorate. George is unique in that he didn’t set out to “be” president; but he did establish many basic principles that are expected of a president today. For example, unlike the kingly rulers of European countries, George did not want to be called “His Excellency” or “His Highness.” “Mr President” was ample title for him. Other executive precedents included an inaugural address, messages to Congress, and the Cabinet form of management. He refused a salary for serving his country; Congress however insisted and provided him with $25,000 annually to help defray costs.

George was an able administrator and a good judge of talent and character. He talked regularly with department heads, tolerated opposing views, and conducted a smooth transition of power to his successor. He was apolitical and opposed the formation of parties. Although he owned slaves, and supported measures passed by Congress to protect slavery, he later became troubled with the institution of slavery and freed his slaves in a 1799 will, with the provision that the old and young freed people be taken care of indefinitely and the young taught to read and write and placed in suitable occupations. He endeavored to assimilate Native Americans into Anglo-American culture but combated indigenous resistance during instances of violent conflict. He urged broad religious freedom in his roles as general and president, emphasizing religious toleration in a nation with numerous denominations. He publicly attended services of different Christian denominations and prohibited anti-Catholic celebrations in the Army. He engaged workers at Mount Vernon without regard for religious belief or affiliation. He was rooted in the ideas, values, and modes of thinking of the Enlightenment, but harbored no contempt of organized Christianity and its clergy, “We have abundant reason to rejoice that in this Land the light of truth and reason has triumphed over  the power of bigotry and superstition.” He proclaimed November 26 as a day of Thanksgiving, always spending the day fasting and taking food to those in prison.

the power of bigotry and superstition.” He proclaimed November 26 as a day of Thanksgiving, always spending the day fasting and taking food to those in prison.

The president’s office was in New York for sixteen months; then moved to Philadelphia, where George and Martha lived from November 1790 to March 1797, before returning to their beloved Mount Vernon at the end of George’s presidency. On December 12, 1799, George inspected his farms on horseback in snow and sleet. He had a sore throat the following day but again went out in freezing, snowy weather to mark trees for cutting. Chest congestion and sore throat followed; he died swiftly on December 14, with Martha seated by his bed. He was 67. As word of his death traveled, church bells rang, businesses closed, and memorial processions were held in major cities. Martha wore a black mourning cape for a year.

George Washington’s legacy endures as one of the most influential in American history. He was called the “Father of His Country” as early as 1778. Congress proclaimed his birthday as a federal holiday in 1885. Many places and monuments have been named in honor of George Washington, most notably the nation’s capital, and the state of Washington. Twentieth-century biographer Douglas Freeman has stated: “The great big thing stamped across that man is character.” Historian David Fischer goes on to define that character as “integrity, self discipline, courage, absolute honesty, resolve, and decision; but also forbearance, decency, and respect for others.”

The mark for the leader of the United States was set high at the start. Which of the next 44 presidents measured up to that?

Which of those characteristics are important to you, as you cast your vote on November 3?