Archive for September 25th, 2020

» posted on Friday, September 25th, 2020 by Linda Lou Burton

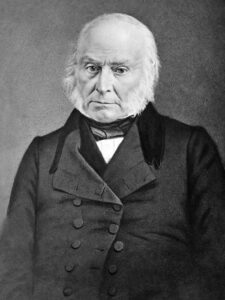

#6. Adams, John Quincy

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – John Quincy Adams (July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was the sixth president of the United States (1825 to 1829) and the eldest son of John and Abigail Adams, two big names in American history. Which puts him in the same situation as being a “preacher’s kid” – you know, everybody expects a certain behavior from you. No matter what you do, or want to do, the jello is already set. John Q certainly emulated his father in a number of ways – he was a one-termer president, he loved politics, and he WROTE EVERYTHING DOWN. He started keeping a daily diary when he was 12 and didn’t stop until he died. Here is an example of an entry from July 1818, when he was 51 years old, and Secretary of State in James Monroe’s cabinet: “I rise usually between four and five — walk two miles, bathe in Potowmack river, and walk home, which occupies two hours — read or write, or more frequently idly waste the time till eight or nine when we breakfast— read or write till twelve or one, when I go to the office; now usually in the carriage — at the office till five then home till dinner. After dinner read newspapers till dark; soon after which I retire to bed.” Would you invite this man to your party? Would he come? Possibly, but only if it was a swim party, and everyone was okay with swimming nude. Because skinny dipping was the way people swam! You folded your clothes, laid them on the riverbank, and jumped in. The “swimming nude in the Potomac” presidential folktale is an actual truth; some of the others are not verifiable.

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – John Quincy Adams (July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was the sixth president of the United States (1825 to 1829) and the eldest son of John and Abigail Adams, two big names in American history. Which puts him in the same situation as being a “preacher’s kid” – you know, everybody expects a certain behavior from you. No matter what you do, or want to do, the jello is already set. John Q certainly emulated his father in a number of ways – he was a one-termer president, he loved politics, and he WROTE EVERYTHING DOWN. He started keeping a daily diary when he was 12 and didn’t stop until he died. Here is an example of an entry from July 1818, when he was 51 years old, and Secretary of State in James Monroe’s cabinet: “I rise usually between four and five — walk two miles, bathe in Potowmack river, and walk home, which occupies two hours — read or write, or more frequently idly waste the time till eight or nine when we breakfast— read or write till twelve or one, when I go to the office; now usually in the carriage — at the office till five then home till dinner. After dinner read newspapers till dark; soon after which I retire to bed.” Would you invite this man to your party? Would he come? Possibly, but only if it was a swim party, and everyone was okay with swimming nude. Because skinny dipping was the way people swam! You folded your clothes, laid them on the riverbank, and jumped in. The “swimming nude in the Potomac” presidential folktale is an actual truth; some of the others are not verifiable.

For instance, the “pet alligator in the White House” simply hasn’t been proven, any more than George Washington’s Hatchett Attacks Cherry Tree story. Maybe LaFayette did give him a baby alligator once – certainly White House occupants are gifted with many unusual objects. Maybe it was kept in the bathtub to surprise guests. But the joke doesn’t really fit into the austere tone of his diary-speak, does it? Still, gift shops sell stuffed alligators as “White House pets.” Let’s switch to serious stuff now. What was John Q’s childhood like?

The Boy

For starters, his stomach was a little unsettled when his father committed an act of TREASON by signing the Declaration of Independence in 1776. This was a crime punishable by death, and John Q was nine years old at the time. While Dad was off on his “revolution” cause, John Q was at home worrying about his mother Abigail – she was a sweetie – and his siblings; sister Amelia was 11, brothers Charles and Thomas were 6 and 4. As “man of the house” John Q worried for their safety. A war went on around his very ears; he actually witnessed the Battle of Bunker Hill with his mother, from the top of a nearby hill. As soldiers passed through town, he feared they might be taken hostage. That was his reality. How would you feel in the middle of all that?

For starters, his stomach was a little unsettled when his father committed an act of TREASON by signing the Declaration of Independence in 1776. This was a crime punishable by death, and John Q was nine years old at the time. While Dad was off on his “revolution” cause, John Q was at home worrying about his mother Abigail – she was a sweetie – and his siblings; sister Amelia was 11, brothers Charles and Thomas were 6 and 4. As “man of the house” John Q worried for their safety. A war went on around his very ears; he actually witnessed the Battle of Bunker Hill with his mother, from the top of a nearby hill. As soldiers passed through town, he feared they might be taken hostage. That was his reality. How would you feel in the middle of all that?

Things got immensely better; an Incredible European Adventure began in 1778 when his father was posted as a special envoy; John Q went to school at the Passy Academy outside of Paris, where, get this – he studied fencing, dance, music, and art with the grandsons of Benjamin Franklin. But things were still a bit quirky; Dad went back to the US, and then back to Europe again as negotiations continued; their ship was leaky; they traveled overland by mule through Spain; some time in Paris but then to Amsterdam, where John Q and Charles briefly studied at the University of Leiden. Charles wanted to go back home, but John Q, at the age of 14, was invited to go to St Petersburg as “translator and personal secretary” to Francis Dana, the newly appointed emissary there. I’d love to read all the diary entries for that period of John Q’s life! Back to The Hague with his father for a while, and in 1785, at the age of 16, he entered Harvard College as an advanced student and completed his studies in two years.

Things got immensely better; an Incredible European Adventure began in 1778 when his father was posted as a special envoy; John Q went to school at the Passy Academy outside of Paris, where, get this – he studied fencing, dance, music, and art with the grandsons of Benjamin Franklin. But things were still a bit quirky; Dad went back to the US, and then back to Europe again as negotiations continued; their ship was leaky; they traveled overland by mule through Spain; some time in Paris but then to Amsterdam, where John Q and Charles briefly studied at the University of Leiden. Charles wanted to go back home, but John Q, at the age of 14, was invited to go to St Petersburg as “translator and personal secretary” to Francis Dana, the newly appointed emissary there. I’d love to read all the diary entries for that period of John Q’s life! Back to The Hague with his father for a while, and in 1785, at the age of 16, he entered Harvard College as an advanced student and completed his studies in two years.

After college, John Q studied law; while preparing for the exam he mastered shorthand and read everything in sight; he passed the bar in 1790 and set up a practice in Boston. Business was slow; he wrote a lot during this time – articles supporting the Washington administration; political issues of the day. It paid off in an unexpected way – Washington, aware of John Q’s support, and his fluency in French and Dutch, appointed him minister to the Netherlands. What a career followed!

Adding Up His Government Positions

- Secretary to US Minister to Russia, 1781

- Minister to the Netherlands, 1794

- Minister to Prussia, 1797-1801

- United States Senator, 1803-08

- Minister to Russia, 1809-11

- Peace Commissioner at Treaty of Ghent, 1814

- Secretary of State, 1817-25 (under Monroe)

- President, 1825-1829

- Member of US House of Representatives, 1831-48

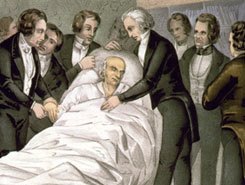

Important to note that workaholic John Q spent 17 years in Congress AFTER he was president. He was 78 when he had a stroke, but he recovered and kept on working. When he entered the House chamber on February 13, 1848, everyone stood and applauded. Then on February 21, as the House members discussed honoring Army officers who served in the Mexican-American War, John Q, who had been a vehement critic of the war, stood to shout “No!” He then collapsed, having suffered a massive cerebral hemorrhage. He died in the Speaker’s Room in the Capitol two days later, his wife by his side. His last words were “I am content.” Someone else there that day was a freshman representative from Illinois, Abraham Lincoln.

Important to note that workaholic John Q spent 17 years in Congress AFTER he was president. He was 78 when he had a stroke, but he recovered and kept on working. When he entered the House chamber on February 13, 1848, everyone stood and applauded. Then on February 21, as the House members discussed honoring Army officers who served in the Mexican-American War, John Q, who had been a vehement critic of the war, stood to shout “No!” He then collapsed, having suffered a massive cerebral hemorrhage. He died in the Speaker’s Room in the Capitol two days later, his wife by his side. His last words were “I am content.” Someone else there that day was a freshman representative from Illinois, Abraham Lincoln.

Love and Marriage and The Screaming Press

John Q met Louisa Catherine Johnson (1775-1852) in 1779 when she was four and he was traveling in France. Her father Joshua was an American merchant who married an Englishwoman; they were living in Nantes, France. Years later, John Q and Louisa met again – he was a 30-year old diplomat and son of the President of the US; she was living in London, where her father was serving as the American consul. John Q had been sent to London from The Hague to exchange the ratifications of the Jay Treaty. The Johnson home was the social center for Americans in London and John Q visited regularly; in time he began dining nightly with the family and the spark was lit. Neither set of parents approved of their marriage; Louisa’s father worried that Yankees made poor husbands; John Q’s mother Abigail worried about the effect a “foreign-born wife” would have on his political dreams. Ahhh. They married on July 26, 1797 in the United Kingdom, and American papers lit in right away. As Abigail Adams had foreseen, Louisa was forced to spend much of her husband’s time in office defending not just their union, but also her loyalty to the Union. The couple lived in Europe until after the birth of their first son; Louisa Adams did not set foot on American soil until she was 26.

John Q met Louisa Catherine Johnson (1775-1852) in 1779 when she was four and he was traveling in France. Her father Joshua was an American merchant who married an Englishwoman; they were living in Nantes, France. Years later, John Q and Louisa met again – he was a 30-year old diplomat and son of the President of the US; she was living in London, where her father was serving as the American consul. John Q had been sent to London from The Hague to exchange the ratifications of the Jay Treaty. The Johnson home was the social center for Americans in London and John Q visited regularly; in time he began dining nightly with the family and the spark was lit. Neither set of parents approved of their marriage; Louisa’s father worried that Yankees made poor husbands; John Q’s mother Abigail worried about the effect a “foreign-born wife” would have on his political dreams. Ahhh. They married on July 26, 1797 in the United Kingdom, and American papers lit in right away. As Abigail Adams had foreseen, Louisa was forced to spend much of her husband’s time in office defending not just their union, but also her loyalty to the Union. The couple lived in Europe until after the birth of their first son; Louisa Adams did not set foot on American soil until she was 26.

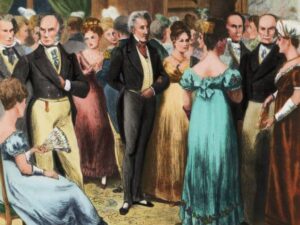

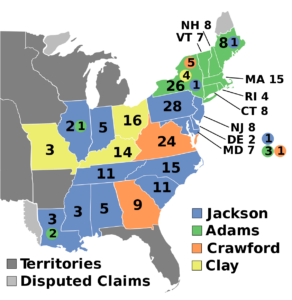

Louisa Adams was sophisticated and urbane; John Q had ambitious political aims, but lacked charisma. She saw herself as his “diplomat,” and became the dominant hostess of Washington, holding balls and parties to raise his social status. (Andrew Jackson is in the center of the painting, John Q to the left) She watched Congress debate, read newspapers, and advised her husband. It worked, to an extent; he was elected president in 1824 but it was a raunchy deal; John Q lost both the popular vote and the electoral votes to Andrew Jackson; but since there was no majority of electoral votes, John Q made a deal with Henry Clay, promising an

Louisa Adams was sophisticated and urbane; John Q had ambitious political aims, but lacked charisma. She saw herself as his “diplomat,” and became the dominant hostess of Washington, holding balls and parties to raise his social status. (Andrew Jackson is in the center of the painting, John Q to the left) She watched Congress debate, read newspapers, and advised her husband. It worked, to an extent; he was elected president in 1824 but it was a raunchy deal; John Q lost both the popular vote and the electoral votes to Andrew Jackson; but since there was no majority of electoral votes, John Q made a deal with Henry Clay, promising an  appointment as Secretary of State if he’d bring in a block of southern-midwestern states. With Clay’s backing, Adams won the contingent election on the first ballot. Louisa did not approve the deal and did not attend her husband’s inauguration.

appointment as Secretary of State if he’d bring in a block of southern-midwestern states. With Clay’s backing, Adams won the contingent election on the first ballot. Louisa did not approve the deal and did not attend her husband’s inauguration.

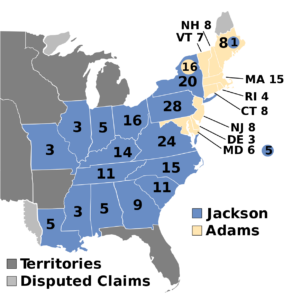

For the four years of his presidency, every aspect of their lives was placed under media scrutiny. Louisa was painted in the press as a foreigner and a Tory of aristocratic birth. She came back describing herself as “the daughter of an American Republican merchant.” The Adams were accused of living like “European royalty” and there was even mention of a “first lady sex scandal with a Russian czar.” It kept them in the papers!  Louisa believed that voters were swayed by their emotions, rather than rational reasoning. (Imagine that!) Shortly before her husband sought reelection, she defended herself in print. She dismissed charges of impropriety and reemphasized the American citizenship she had been born with. It wasn’t enough; during John Q’s presidency, the Democratic-Republican Party split; the Democrats who supported Jackson proved to be more effective political organizers than the Republicans who supported Adams; Jackson decisively won, receiving 178 electoral votes to Adams’ 83.

Louisa believed that voters were swayed by their emotions, rather than rational reasoning. (Imagine that!) Shortly before her husband sought reelection, she defended herself in print. She dismissed charges of impropriety and reemphasized the American citizenship she had been born with. It wasn’t enough; during John Q’s presidency, the Democratic-Republican Party split; the Democrats who supported Jackson proved to be more effective political organizers than the Republicans who supported Adams; Jackson decisively won, receiving 178 electoral votes to Adams’ 83.

Historians generally concur that John Quincy Adams was one of the greatest diplomats and secretaries of state in American history; though they typically rank him as a mediocre president. He had an ambitious agenda but could not get it passed by Congress.

Historians generally concur that John Quincy Adams was one of the greatest diplomats and secretaries of state in American history; though they typically rank him as a mediocre president. He had an ambitious agenda but could not get it passed by Congress.

Do you see sadness reflected in his eyes in Matthew Brady’s “first photograph” of a president? Perhaps, but John Quincy Adams’ life was filled with adventure, romance, and a great swimming hole, worthy of a Mark Twain tale. His last three words were “I am content.”

Maybe he DID have a pet alligator.