Archive for October 5th, 2020

» posted on Monday, October 5th, 2020 by Linda Lou Burton

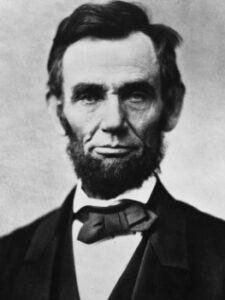

#16. Lincoln, Abraham

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States from 1861 to 1865. I’m finding it very hard to write about Abraham Lincoln; for one, there’s probably been more written about this president than any; he was neither obscure nor forgettable. So I’m guessing there isn’t much about the man you don’t already know, or have an opinion about. And I’ve already written a lot about “Abe” – on the Journey I came upon his statue everywhere; in front of the capitol in Charleston, West Virginia, a pensive, sad figure that took research to determine if he was sad about the war, or family matters, or just suffering the general melancholia we’ve heard about. In Frankfort, Kentucky his statue stands in the capitol rotunda, with Jefferson Davis nearby. I found that not only odd, but strangely heartwarming – two men on different sides, in a position to communicate across the room. In Springfield, Illinois I got the full package – I visited his tomb, his home, his law office (where his kids romped around while he was  absorbed in his work) and the topper of it all – the Disney version of Lincolnland, with holograph ghosts, cannon fire jolting your seat in the 4D show, and a modern-day telecast of the 1860 election, So I refer you to those posts rather than tell it all again; the links are at the end.

absorbed in his work) and the topper of it all – the Disney version of Lincolnland, with holograph ghosts, cannon fire jolting your seat in the 4D show, and a modern-day telecast of the 1860 election, So I refer you to those posts rather than tell it all again; the links are at the end.

Instead, I’m focusing on four moments in time: his first inauguration, the Emancipation Proclamation, his second inauguration, and his funeral. I grew up in the south; a number of my ancestors served in the Confederate Army and a few in the Union Army; one family had sons serving in both, and two sons hiding in the woods to avoid either. Lincoln’s presidency was a time of heart-rending confusion and upheaval; a time when beliefs and behaviors learned at Daddy’s knee were brought into question. Not just actions were forced to change, but feelings about those actions. It was emotional. That’s the can of worms that came with Lincoln’s job.

1861: First Inauguration

Lincoln won 180 electoral votes on November 6, 1860. Seven deep-south states declared their secession from the Union and formed the Confederate States of America before he arrived in Washington for his inauguration. Word of an assassination conspiracy brought him into the city through Baltimore at midnight on a special train. The air was thick with rumors of “rebel plots” to assassinate or capture Lincoln before he took office. General Winfield Scott was charged with providing protection for Lincoln; he too received death threats. On the procession to the Capitol, Lincoln’s carriage was so closely surrounded by marshals and cavalry it was almost hidden from view.

Lincoln won 180 electoral votes on November 6, 1860. Seven deep-south states declared their secession from the Union and formed the Confederate States of America before he arrived in Washington for his inauguration. Word of an assassination conspiracy brought him into the city through Baltimore at midnight on a special train. The air was thick with rumors of “rebel plots” to assassinate or capture Lincoln before he took office. General Winfield Scott was charged with providing protection for Lincoln; he too received death threats. On the procession to the Capitol, Lincoln’s carriage was so closely surrounded by marshals and cavalry it was almost hidden from view.

Nevertheless, on March 4, 1861, Abraham Lincoln stood on the East Portico before a crowd of 25,000 and delivered his first address to a nation in trouble. Indicating that he’d leave aside matters of no special anxiety, he made these points:

- Slavery: “I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.”

- Legal status of the South: “I have just taken an oath to preserve, protect, and defend the United States Constitution, which enjoins me to see that the laws of the Union are faithfully executed in all states, even those that have seceded.”

- Use of force: “There will be no use of force against the South, unless it proves necessary to hold, occupy, and possess the property and places belonging to the federal government. If the South choses to actively take up arms against the Government, their insurrection will meet a firm and forceful response.”

Lincoln concluded his speech with a plea for calm and cool deliberation in the face of mounting tension throughout the nation. He assured the rebellious states that the Federal government would never initiate any conflict with them. Though most of the northern press praised the speech, it was met with contempt in the south.

1862: Emancipation Proclamation

The Federal government’s power to end slavery was limited by the Constitution. In June 1862, Congress passed an act banning slavery on all federal territory, which Lincoln signed. Privately, Lincoln concluded that the Confederacy’s slave base had to be eliminated. Publicly he said this:

My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that. What I do about slavery, and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union; and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union … I have here stated my purpose according to my view of official duty; and I intend no modification of my oft-expressed personal wish that all men everywhere could be free.

The Emancipation Proclamation became effective January 1, 1863 and affirmed the freedom of slaves in the ten states not then under Union control. With the abolition of slavery now a military objective, Union armies advancing south liberated three million slaves; enlisting former slaves became official policy. In a letter to Andrew Johnson, then military governor of Tennessee, Lincoln encouraged him to lead the way in raising black troops, stating: “The bare sight of 50,000 armed and drilled black soldiers on the banks of the Mississippi would end the rebellion at once.”

1865: Second Inauguration

The Republicans nominated Abraham Lincoln again in 1864, selecting Andrew Johnson as his running mate. Lincoln ran under the label of the new Union Party, to include War Democrats as well as Republicans. Lincoln pledged in writing that if he lost the election, he would still defeat the Confederacy before leaving the White House. His pledge was put into a sealed envelope; which he asked his cabinet members to sign. The pledge:

“This morning, as for some days past, it seems exceedingly probable that this Administration will not be re-elected. Then it will be my duty to so co-operate with the President elect, as to save the Union between the election and the inauguration; as he will have secured his election on such ground that he cannot possibly save it afterward.”

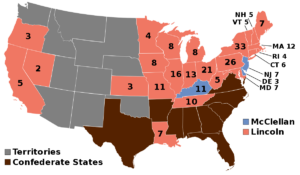

Sherman captured Atlanta in September. On November 8, the Lincoln/Johnson ticket won all but three states – Kentucky, Delaware, and New Jersey. Only twenty-five states participated in the election; of the seceded states Tennessee and Louisiana chose electors who voted for Lincoln; their votes were rejected by Congress. Three new states participated for the first time: Kansas, West Virginia, and Nevada. Of the 40,247 army votes cast, Lincoln received 76%.

Sherman captured Atlanta in September. On November 8, the Lincoln/Johnson ticket won all but three states – Kentucky, Delaware, and New Jersey. Only twenty-five states participated in the election; of the seceded states Tennessee and Louisiana chose electors who voted for Lincoln; their votes were rejected by Congress. Three new states participated for the first time: Kansas, West Virginia, and Nevada. Of the 40,247 army votes cast, Lincoln received 76%.

On March 4, 1865, Lincoln delivered his second inaugural address. In it, he deemed the war casualties to be God’s will.

“Fondly do we hope—fervently do we pray—that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man’s 250 years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said 3,000 years ago, so still it must be said, “the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether”. With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.”

Before Lincoln was sworn in, Vice President-elect Andrew Johnson took his oath of office in the Senate Chamber. Obviously inebriated, he later explained that he had been drinking to offset the pain of typhoid fever, but the press ridiculed him as a “drunken clown.” This was the first inauguration to be extensively photographed; one photo is thought to show John Wilkes Booth, a well-known actor and Confederate spy.

1865 Timeline: Assassination and Burial

- On April 9 General Robert E Lee surrendered his Confederate troops to Ulysses S Grant, marking the beginning of the end of the Civil War.

- On April 11 Abraham Lincoln gave a speech in which he promoted voting rights for blacks. John Wilkes Booth was there.

- On the afternoon of April 14 Lincoln and Johnson met for the first time since the inauguration. John Wilkes Booth dropped by Kirkwood house that day and left his card with Johnson’s personal secretary with the message “Don’t wish to disturb you, are you home?”

- On evening of April 14, Abraham and Mary Lincoln attended a play at Ford Theater. Our American Cousin was a comedy, a farce about an awkward, boorish-but-honest American, heading off to England to claim the family estate. John Wilkes Booth was there. He was familiar with the play, and waited for the line that he knew would draw loud laughter; when the character of Asa Trenchard says to Mrs Mountchessington: “Don’t know the manners of good society, eh? Well, I guess I know enough to turn you inside out, old gal – you sockdologizing old man-trap!” At that moment John Wilkes Booth entered the Lincoln box and shot Abraham Lincoln in the back of the head, then leapt onto the stage and escaped through the back to a horse he had left waiting in the alley. Lincoln was first attended by doctors there, then taken across the street to Petersen House. He remained in a coma for eight hours.

- On April 15 at 7:22 AM Lincoln died. His flag-enfolded body was escorted in the rain to the White House by bareheaded Union officers as the city’s church bells tolled. Andrew Johnson was sworn in between 10 and 11 in the presence of most of the Cabinet. Between April 15-19 Lincoln’s body lay in state in the East Room of the White House.

- On April 19 the coffin, attended by large crowds, was transported in a procession down Pennsylvania Avenue to the Capitol Rotunda, where a ceremonial burial service was held. The body again lay in state on the 20th and on the early morning of the following day a prayer service was held for the Lincoln cabinet officials.

- On April 21 Lincoln’s coffin was removed to the depot and placed on a train, which traveled through 444 communities and seven states before arriving in Springfield, Illinois, for internment on May 4.

- On April 26, John Wilkes Booth was caught and killed.

I’d like to talk more about Mary Todd Lincoln, and the Lincoln boys. Back in the happier days of “life in Springfield” when the boys were small, and romping around the little town, I would have invited the whole family over for dinner; a picnic maybe.

But then, everything got so sad.

For Lighter Reading

The Citizen Key, Charleston, West Virginia https://capitalcitiesusa.org/?p=8362#

An April Afternoon, Frankfort, Kentucky https://capitalcitiesusa.org/?p=9950#

Honestly Abe, Springfield, Illinois https://capitalcitiesusa.org/?p=9141#