» posted on Wednesday, May 1st, 2013 by Linda Lou Burton

Birth Of A Capital City

Linda Burton posting from Indianapolis, Indiana –How many capital cities have the name of the state within the name of the city? The answer is at the end of this post, but obviously Indianapolis is one. The name was created by joining “Indiana” with “polis,” which is the Greek word for “city.” Yes, Indianapolis literally means Indiana City (like Oklahoma City, a trivia hint for you). So the next question is “what does Indiana mean?” I won’t go into all of the Indian wars and treaties that occurred as the United States expanded westward; I’ll start with July 4, 1800, when Indiana Territory was pulled out of the larger Northwest Territory. Vincennes, a former French trading post and one of the only white settlements in the vast territory, was named capital. At that time about five thousand white Europeans lived north of the Ohio River; Native Americans

Linda Burton posting from Indianapolis, Indiana –How many capital cities have the name of the state within the name of the city? The answer is at the end of this post, but obviously Indianapolis is one. The name was created by joining “Indiana” with “polis,” which is the Greek word for “city.” Yes, Indianapolis literally means Indiana City (like Oklahoma City, a trivia hint for you). So the next question is “what does Indiana mean?” I won’t go into all of the Indian wars and treaties that occurred as the United States expanded westward; I’ll start with July 4, 1800, when Indiana Territory was pulled out of the larger Northwest Territory. Vincennes, a former French trading post and one of the only white settlements in the vast territory, was named capital. At that time about five thousand white Europeans lived north of the Ohio River; Native Americans  occupied most of the Territory, referred to as “Land of the Indians,” aka Indiana. Fast forward to December 1813: Corydon was named the second capital of Indiana Territory, and the wheels began to turn for statehood. President James Madison approved Indiana’s admission into the Union December 11, 1816 as the 19th state. The capital could not be located in the central part of the state at that time because the land was controlled by Native Americans; however in an 1818 treaty the area was opened for white settlement; an unprecedented migration followed. A central location for a capital city became imperative then; on January 11, 1820 Governor Jennings commissioned 10 men to select a site for the permanent capital. They chose a spot at the junction of Fall Creek and White River; the legislature ratified their selection January 6, 1821, and the building of a capital city began. Enter Alexander Ralston.

occupied most of the Territory, referred to as “Land of the Indians,” aka Indiana. Fast forward to December 1813: Corydon was named the second capital of Indiana Territory, and the wheels began to turn for statehood. President James Madison approved Indiana’s admission into the Union December 11, 1816 as the 19th state. The capital could not be located in the central part of the state at that time because the land was controlled by Native Americans; however in an 1818 treaty the area was opened for white settlement; an unprecedented migration followed. A central location for a capital city became imperative then; on January 11, 1820 Governor Jennings commissioned 10 men to select a site for the permanent capital. They chose a spot at the junction of Fall Creek and White River; the legislature ratified their selection January 6, 1821, and the building of a capital city began. Enter Alexander Ralston.

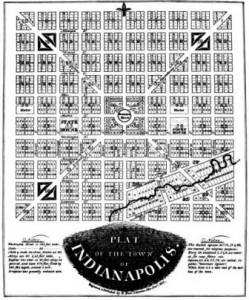

Ralston was an engineer, and his credentials included serving as Pierre L’Enfant’s personal assistant during the planning of Washington, DC. Ralston adapted the plan L’Enfant used for Washington; for Indianapolis he designed a city block one square mile in area with a circle at the center from which four diagonal roads extended radially outward. Most of Ralston’s plan was great; the city’s center grid is easy to maneuver today. Some of it took years to realize, and one of his primary ideas was discarded; you’ll see why. Ralston’s planning took place between 1821 and 1827; at the center of his original plan was Governor’s Circle, a large circular commons, which was to be the site of the governor’s house; Ralston himself designed the mansion which was built in 1827. But oops! The governor refused to live in it. “A complete lack of privacy” was the reason given, and you can see why;

Ralston was an engineer, and his credentials included serving as Pierre L’Enfant’s personal assistant during the planning of Washington, DC. Ralston adapted the plan L’Enfant used for Washington; for Indianapolis he designed a city block one square mile in area with a circle at the center from which four diagonal roads extended radially outward. Most of Ralston’s plan was great; the city’s center grid is easy to maneuver today. Some of it took years to realize, and one of his primary ideas was discarded; you’ll see why. Ralston’s planning took place between 1821 and 1827; at the center of his original plan was Governor’s Circle, a large circular commons, which was to be the site of the governor’s house; Ralston himself designed the mansion which was built in 1827. But oops! The governor refused to live in it. “A complete lack of privacy” was the reason given, and you can see why;  all roads converged on the mansion’s steps. The house was demolished in 1857, and that’s the site today of the 284-foot tall limestone and bronze Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument, erected in 1901 and perfectly centered in what is now called Monument Circle, a beautiful and unique spot and a true city “hub.”

all roads converged on the mansion’s steps. The house was demolished in 1857, and that’s the site today of the 284-foot tall limestone and bronze Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument, erected in 1901 and perfectly centered in what is now called Monument Circle, a beautiful and unique spot and a true city “hub.”

As the planning and design were underway, the city-to-be needed a name. Tecumseh was suggested; he was the Shawnee Indian leader who opposed the United States in numerous wars, but had become somewhat of a folk hero. Jeremiah Sullivan, an Indiana judge, came up with “Indianapolis” instead; the public opposed it at first but eventually began to like it. It stuck.

So we have Alexander Ralston, who created the design plan for Indianapolis, and Jeremiah Sullivan, who created the city’s name. There is one other person whose contribution to the “birth of a capital city” was recorded in personal detail; it was Samuel Merrill, State Treasurer. On January 20, 1824, the legislature declared that the permanent seat of government would be located in Indianapolis as of January 10, 1825, and thereafter. Remember, the capital was in Corydon at the time, some one hundred sixty miles to the south. As Treasurer, Merrill had the task of moving the state’s records and money to Indianapolis. He made an advance trip to become acquainted with the roads and fording places; on his return to Corydon he sold furniture that could not be moved, and packed the books and records. The state’s treasury of silver was secured in sturdy wooden boxes.

In autumn of 1824 the move north began; I found these excerpts from Merrill’s written account of the trip in the September 1931 issue of the Indiana Magazine of History:

The journey of about one hundred and sixty miles occupied two weeks. The best day’s travel was eleven miles. One day the wagons accomplished but two miles, passage through the woods having to be cut on account of the impassable character of the roads. Four four-horse wagons and one or two saddle-horses formed the means of conveyance for the two families, consisting of about a dozen persons, and for a printing press and the state treasury of silver in strong wooden boxes. The gentlemen slept in the wagons or on the ground to protect the silver, the families found shelter at night in log cabins which stood along the road at rare though not inconvenient intervals. The country people were, many of them, as rude as their dwellings, which usually consisted of but one room, serving for all purposes of domestic life, cooking, eating, sleeping, spinning and weaving, and the entertainment of company.

It is said that Merrill slept with two flint-lock horse pistols under his head, carefully loaded for robbers. Merrill’s sister-in-law Mary Catherine Anderson also kept an account of the “moving of the capital;” her notes appeared in the magazine too:

It was a bright and lovely day in October, 1824, that we left Corydon for the seat of government. The party consisted of six of the Merrill family, Mr. Merrill, my sister, and their three children, my brother William and this scribbler. My sister had heard that the road most of the way was impassable; she insisted that Mr. Siebert, a large man with a team of horses, none stronger in Indiana, should take us. Four of the horses were white, the fifth gray, called the lead horse…. I could not ride in the wagon, as it was covered, and made me sick; but my sister and her children rode all the way to Indianapolis. I walked the eleven miles of our first day’s journey. We were, I think, ten days on our way. The treasury box was large and strong. Whether there was much money in it, I cannot say; but I think not much. This box had to have a place in this large wagon, indeed wherever we or the Merrill family went, this box was sure to go….

We know that the family of State Printer John Douglass was in the second wagon; their cow, tied to the back of the wagon, also made the journey. As the party approached Indianapolis, coming along the road now called South Meridian Street, the happy teamster Seibert, feeling that this was the proudest day of his life, decked the horses with loud sounding bells, and sent forward a … man who chanced to be passing to inform the people that the seat of government was coming. At the word, out poured most of the five hundred inhabitants – boys, girls, men, and women – to see a sight that will never again be seen in Indiana.

The following bill was presented to the state legislature by Merrill for moving the records:

- To Messrs Posey and Wilson for boxes $7.56

- To Mr Lefler for one box $.50

- To Seybert & Likens for transportation of 3,945 lbs at $1.90 per hundred $74.95

- To Jacob & Samuel Kenoyer for transportation of one load $35.06

- Total $118.07

- Deduct proceeds of sale of furniture at Corydon, November 22nd, 1824 $52.52 = $65.55

An additional $9.50 was also granted to Merrill for the transportation of the state library, and he was paid $100 for personal trouble and expenditure in packing and moving the property of the state.

Many more have been influential in making Indianapolis the capital city it is today; I’ll cover some of them in later posts. But for now you know of three who contributed their ideas, vision, and hard work, back in the very beginning.

Answer to Trivia Question: Two. Indianapolis, Indiana and Oklahoma City, Oklahoma