» posted on Sunday, February 17th, 2013 by Linda Lou Burton

And Here’s The Steeple

Linda Burton posting from Columbia, South Carolina – It was a little more peaceful in downtown Columbia today than it was on this day 148 years ago. February 17 was the day in 1865 when much of Columbia was burned; General Wade Hampton’s Confederate cavalry surrendered the city to General William Sherman’s Union troops; a story that is told and retold in historical markers all over town. Today’s downtown is moderate in size; the streets are wide and palmettos edge the sidewalks. The tallest buildings appear to be banks, clustered near the State House on Main, or Gervais, but holding their own in the height department are the church steeples, some topped with crosses, some not. Columbia is a “planned” city; it was chosen as the new state capital in 1786, incorporated as a village in 1805 and a city in 1854. Designed as a town of 400 blocks in a 2-mile square along the river, the blocks were divided in lots of 0.5 acres; perimeter streets and two through streets were  150 feet wide. Thank the mosquito for that – it was the belief at the time that dangerous mosquitos could not fly more than 60 feet without dying of starvation! As I drove those wide streets today, I couldn’t help but notice steeples poking up everywhere, so the GPS and I decided to do a little bird-dog tracking. It was an easy search on a sleepy Sunday afternoon; traffic was almost nil. I tried to imagine the noise of 1865, the smoke, and the fear. What would be burned next? What saved? And that led me to the First Baptist Church.

150 feet wide. Thank the mosquito for that – it was the belief at the time that dangerous mosquitos could not fly more than 60 feet without dying of starvation! As I drove those wide streets today, I couldn’t help but notice steeples poking up everywhere, so the GPS and I decided to do a little bird-dog tracking. It was an easy search on a sleepy Sunday afternoon; traffic was almost nil. I tried to imagine the noise of 1865, the smoke, and the fear. What would be burned next? What saved? And that led me to the First Baptist Church.

Was the First Baptist Church on Hampton Street a target? Union troops would have known it was where the Secession Convention met in December 1860; the first move of the Civil War. The Convention met there because it was the largest meeting place in Columbia at the time. According to the historical marker out front, First Baptist was organized in 1809 and in 1811 built a church on Sumter Street. That’s the building that was burned that day. However, First Baptist had built a new church in 1859; that’s actually where the Secession Convention met in 1860. There are several different stories about why First Baptist was spared – one says the First Baptist sexton led Union troops to the Washington Street Methodist in a lie; another says troops believed the old Baptist Church was the site; for sure, both those churches were burned, and the First Baptist was not. It was used for services till 1992 and is still in use for other activities. A tulip poplar near the front door was blooming out today; Hampton Street was quiet. Tour information 803-256-4251.

Was the First Baptist Church on Hampton Street a target? Union troops would have known it was where the Secession Convention met in December 1860; the first move of the Civil War. The Convention met there because it was the largest meeting place in Columbia at the time. According to the historical marker out front, First Baptist was organized in 1809 and in 1811 built a church on Sumter Street. That’s the building that was burned that day. However, First Baptist had built a new church in 1859; that’s actually where the Secession Convention met in 1860. There are several different stories about why First Baptist was spared – one says the First Baptist sexton led Union troops to the Washington Street Methodist in a lie; another says troops believed the old Baptist Church was the site; for sure, both those churches were burned, and the First Baptist was not. It was used for services till 1992 and is still in use for other activities. A tulip poplar near the front door was blooming out today; Hampton Street was quiet. Tour information 803-256-4251.

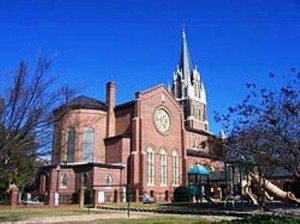

Around the corner and a block or two to the Washington Street United Methodist Church. Yes, it was burned 148 years ago. Columbia’s Methodist history goes back to 1803; the church that was burned was an 1832 construction. The building I see today was reconstructed beginning in 1866 using salvaged brick and clay mortar. It was dedicated in 1875 and has been in use since. Because several Methodist churches have sprung from its founding, it has been called the “Mother Chu rch” of Methodism in Columbia. On this quiet tree-lined street today, a chilly breeze cut across the sunshine; no sign of smoke, or flames. Tour information 803-256-2417.

rch” of Methodism in Columbia. On this quiet tree-lined street today, a chilly breeze cut across the sunshine; no sign of smoke, or flames. Tour information 803-256-2417.

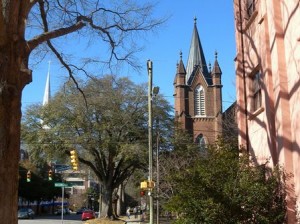

A strange juxtaposition appears in my camera lens as I stand beside a building that makes up the complex of the First Presbyterian Church. The First Baptist steeple is visible through the trees on the left, the Washington United Methodist steeple straight ahead. I turn and read the marker before me now; First Presbyterian goes back to 1795 and its 188-foot steeple was once the tallest structure in Columbia. It was spared when others were burned; I don’t find an  accompanying legend as to why. The English Gothic structure was built in 1854; the cemetery, once a public burying ground, was allotted to the church in 1813. College presidents, US Senators, and the parents of Woodrow Wilson are buried here. I wish I had time to explore the cemetery, they do offer churchyard tours. 803-799-9062.

accompanying legend as to why. The English Gothic structure was built in 1854; the cemetery, once a public burying ground, was allotted to the church in 1813. College presidents, US Senators, and the parents of Woodrow Wilson are buried here. I wish I had time to explore the cemetery, they do offer churchyard tours. 803-799-9062.

I find two more churches that were spared on that fateful day – Trinity Episcopal and St Peter’s Catholic. Local tradition is that laymen took down the Episcopal signs and put paper-mâché crosses on the roof of Trinity Episcopal when Sherman’s troops entered Columbia on February 17; they hoped this would protect the church because Sherman was Catholic. The rectory burned in the fire, but the church survived. In June 1865, it is told, the commander of  the Columbia garrison of the Union Army ordered the minister to say the prayer for the president that’s in the Book of Common Prayer. When the minister began the prayer, Parish members rose from their knees. Trinity Episcopal Parish was organized in 1812; the church on Sumter Street, just across from the State House, was built in 1846. Former governors and three Wade Hamptons are buried in the adjacent cemetery.

the Columbia garrison of the Union Army ordered the minister to say the prayer for the president that’s in the Book of Common Prayer. When the minister began the prayer, Parish members rose from their knees. Trinity Episcopal Parish was organized in 1812; the church on Sumter Street, just across from the State House, was built in 1846. Former governors and three Wade Hamptons are buried in the adjacent cemetery.

As to St Peter’s Catholic Church on Assembly Street, I learn that the first church in Columbia was completed in 1824 and demolished in the early 1900’s so a new church could be built; it  was completed in 1908. I catch a few important names with regard to architects: Robert Mills designed the first church; Frank Milburn the second. And John Niernsee is buried here; both Niernsee and Milburn were involved in the design of the State House. Tour information 803-779-0036.

was completed in 1908. I catch a few important names with regard to architects: Robert Mills designed the first church; Frank Milburn the second. And John Niernsee is buried here; both Niernsee and Milburn were involved in the design of the State House. Tour information 803-779-0036.

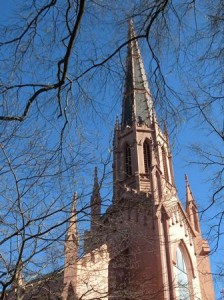

The GPS directed me several blocks more to Richland Street, and Ebenezer Lutheran Church.  The Lutheran congregation was organized in Columbia in 1830; its church was burned in 1865 and rebuilt in 1870 with the help of northern Lutherans. That building in still in use for classes, but the main sanctuary of today was added in 1931; its steeple stands tall and stunning against the February sky. Tour information 803-765-9430.

The Lutheran congregation was organized in Columbia in 1830; its church was burned in 1865 and rebuilt in 1870 with the help of northern Lutherans. That building in still in use for classes, but the main sanctuary of today was added in 1931; its steeple stands tall and stunning against the February sky. Tour information 803-765-9430.

I know that controversy has surrounded the burning of Columbia since that day 148 years ago. Firsthand accounts by local residents and Union soldiers tell a tale of revenge by Union troops for Columbia’s role in leading Southern states to secede. Other accounts claim it was the fault of the Confederacy. One historian holds Governor Magrath and General Hampton partly accountable; some wanted to surrender the city from a safe distance, but the Governor vetoed the idea, and General Hampton vowed to defend the city from “house to house.” We know that bales of cotton were stacked in the streets in a defensive move. We know that as Union forces entered the city and General Hampton’s cavalry retreated, liberated Federal prisoners and emancipated slaves began to appear in the streets. We know that liquor supplies were ample that day, and winds were high. General Sherman affirmed that he ordered militarily significant structures, such as the Confederate Printing Plant, railroad depots, warehouses, and machine shops destroyed, but blamed  retreating Confederate soldiers for setting fire to those bales of cotton. As the high winds caused flames to spread that day, fire companies – both municipal and some of the Union army – could not contain the destruction in the chaos, despite who might have set the torch. I headed on down Richland, past the pretty houses with the tall columns and the potted palms on the porch.

retreating Confederate soldiers for setting fire to those bales of cotton. As the high winds caused flames to spread that day, fire companies – both municipal and some of the Union army – could not contain the destruction in the chaos, despite who might have set the torch. I headed on down Richland, past the pretty houses with the tall columns and the potted palms on the porch.