» posted on Wednesday, January 23rd, 2013 by Linda Lou Burton

Story Telling Time

Linda Burton posting from Montgomery, Alabama – The prettiest thing in the Alabama state capitol is the spiral staircase. At least, that’s my opinion; I had to stop the minute I entered the door and look up, in wonder. It is stunning, and mysterious. And then I noticed there are two; a pair of cantilevered spiral staircases graces the entrance hall, curving upwards for three stories in simple elegance, one of the building’s finest architectural features. This capitol was in use by 1851; the story goes the staircases were built by Horace King, a slave who was freed in 1846. Horace was

Linda Burton posting from Montgomery, Alabama – The prettiest thing in the Alabama state capitol is the spiral staircase. At least, that’s my opinion; I had to stop the minute I entered the door and look up, in wonder. It is stunning, and mysterious. And then I noticed there are two; a pair of cantilevered spiral staircases graces the entrance hall, curving upwards for three stories in simple elegance, one of the building’s finest architectural features. This capitol was in use by 1851; the story goes the staircases were built by Horace King, a slave who was freed in 1846. Horace was  known in Alabama, and surrounding states, for his talent as a bridge builder; because of this the Alabama legislature passed a special law exempting him from the state’s manumission laws, which required freed slaves to leave the state within a year of gaining their freedom. So Horace stayed, and after the Civil War he got into politics; serving two terms in the Alabama House of Representatives, in the building he helped design and build. The Alabama capitol is full of stories, as is true of any building of this many years. Two

known in Alabama, and surrounding states, for his talent as a bridge builder; because of this the Alabama legislature passed a special law exempting him from the state’s manumission laws, which required freed slaves to leave the state within a year of gaining their freedom. So Horace stayed, and after the Civil War he got into politics; serving two terms in the Alabama House of Representatives, in the building he helped design and build. The Alabama capitol is full of stories, as is true of any building of this many years. Two  of the most famous are its use during the Civil War, as it briefly served as capitol of the Confederate States before that seat of government moved to Richmond; and its use as a destination point during the Civil Rights movement in the 1960’s. Today I was looking for stories; I’d heard about the murals so I headed for the second floor; I knew that much of the history of Alabama was displayed beneath the dome. Another story behind that; artist Roderick MacKenzie lived in an Alabama orphanage for a time. A freed slave and an orphan, two men whose creativity became part of the Alabama story.

of the most famous are its use during the Civil War, as it briefly served as capitol of the Confederate States before that seat of government moved to Richmond; and its use as a destination point during the Civil Rights movement in the 1960’s. Today I was looking for stories; I’d heard about the murals so I headed for the second floor; I knew that much of the history of Alabama was displayed beneath the dome. Another story behind that; artist Roderick MacKenzie lived in an Alabama orphanage for a time. A freed slave and an orphan, two men whose creativity became part of the Alabama story.

Roderick MacKenzie (1865-1941) was born in England; his family immigrated to Mobile, Alabama in 1872. When Roderick’s mother died, his father had to split the family; Roderick and one sibling were sent to Mobile’s Episcopal Church Home. His church family recognized his talent and provided scholarship funds so he could study art in Boston. He went on to study in Paris; he lived in London, and then India; his reputation grew and he was well-known for his large-scale works. But his nostalgia for the south, plus political unrest abroad, brought him back to Alabama in 1914, where he opened a studio in Mobile. In 1920 he began a project which occupied the next five years – he did 43 pastels of the Alabama Steel Industry, working on-site and mainly at night at a plant in Ensley; his work was recognized for his use of vivid color against black. In 1926 he was chosen by the State Capitol Commission to paint  eight murals for the rotunda, depicting episodes from Alabama history. He did the work in his studio in Mobile; the canvases were installed in the capitol in July 1930.

eight murals for the rotunda, depicting episodes from Alabama history. He did the work in his studio in Mobile; the canvases were installed in the capitol in July 1930.

On the second-floor balcony I could see the murals; eight of them spanning almost four hundred years, from 1540 to 1930, when he completed the works. I centered myself to find the first; “Hostile Meeting of DeSoto, Spanish Explorer, and Tuskaloosa, Indian Chieftain, 1540.” Tuskaloosa was leader of many native people in what is now Alabama; he defended his fortified village against DeSoto as the Spaniards passed through his territory. The Choctaw and Creek are descended from Tuskaloosa’s people; the city of Tuscaloosa, (capital of  Alabama from 1826-1846) was named for him. “Tuskaloosa,” incidentally, is derived from the western Muskogean language elements taska and losa, meaning “Black Warrior.”

Alabama from 1826-1846) was named for him. “Tuskaloosa,” incidentally, is derived from the western Muskogean language elements taska and losa, meaning “Black Warrior.”

The second mural is “French Establishing First White Colony in Alabama under Iberville and Bienville, Mobile, 1702-1711.” The French were the first to colonize the area around Mobile Bay; a subject familiar to artist MacKenzie, I’m sure, as his studio was located on Dauphin Street in Mobile. English and Spanish colonizers succeeded the French and by 1813 Mobile came under the American flag.

Mural three is “Surrender of William Weatherford, Hostile Creek Leader, to General Andrew Jackson, 1814.” The defeat of the Creek nation at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend made the eventual expulsion of Alabama’s native inhabitants inevitable; mural four, “Pioneer Home-seekers Led into the Alabama Wilderness by Sam Dale, 1816” shows parties of white settlers being led into the Tombigbee River basin north of Mobile.

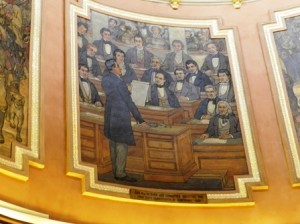

Mural five tells the story of Alabama’s beginnings as a state; “Governor William Bibb and Committee Drafting the First State Constitution at Huntsville, 1819.” Forty-four delegates  convened in Huntsville, Alabama on July 5, 1819 to draft a constitution. It was formally adopted August 2; Alabama was admitted to the Union as the 22nd state December 14, 1819.

convened in Huntsville, Alabama on July 5, 1819 to draft a constitution. It was formally adopted August 2; Alabama was admitted to the Union as the 22nd state December 14, 1819.

Since 1817, when it became a separate territory, Alabama has had five capitals. Saint Stephens, in southwest Alabama, was designated the temporary seat of government by Congressional act when the territory was created, and two sessions of the territorial legislature met there. Then the Constitutional Committee, and the first session of the General Assembly met at Huntsville, though Cahaba had been chosen by the territorial legislature. Cahaba, at the confluence of the Cahaba and Alabama Rivers, served as capital until 1826, when it was moved from that flood-prone area to Tuscaloosa.

Tuscaloosa was a thriving community located on the shoals of the Black Warrior River and had been a strong candidate for the capital site when Cahaba was chosen for the honor in 1819. It served as the home for Alabama’s government beginning in 1826, but as population shifted in the state, it was decided a more central area was needed. Montgomery, on the Alabama River, won the 16-ballot contest in the General Assembly.

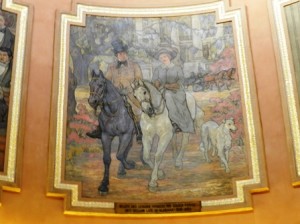

Mural six, entitled “Wealth and Leisure Produce the Golden Period of Antebellum Life In Alabama, 1840-1860” shows the effects of “cotton riches” on the state in the two decades before the Civil War; mural seven is “Secession and the Confederacy, Inauguration of President Jefferson Davis, 1861.”

Mural six, entitled “Wealth and Leisure Produce the Golden Period of Antebellum Life In Alabama, 1840-1860” shows the effects of “cotton riches” on the state in the two decades before the Civil War; mural seven is “Secession and the Confederacy, Inauguration of President Jefferson Davis, 1861.”

The last mural is “Prosperity Follows Development of Resources, Agriculture, Commerce, and Industry, 1874-1930,” and it focuses on the development of the steel industries, due to Alabama’s rich iron and coal deposits, another topic with which MacKenzie was familiar.

Many stories over that 400 years, and many more in this building since the murals were painted. This is actually the second building on this site; the first burned in 1849. Since this building was completed in 1851, a south wing was added in 1906; a north wing in 1911.

In 1940 the Supreme Court moved into a separate building on Dexter Avenue; the Department of Archives moved out too. In 1985 the Legislature moved into what is now called the Alabama State House, where the 35 senators and 105 representatives continue to meet today (although the Constitution states they are to meet in the capitol). The Governor’s office remains in the capitol, though not accessible to the public; rooms open to visitors are the Old Supreme Court Chamber, and the old Senate and House Chambers, now restored to their 19th century appearance.

In 1940 the Supreme Court moved into a separate building on Dexter Avenue; the Department of Archives moved out too. In 1985 the Legislature moved into what is now called the Alabama State House, where the 35 senators and 105 representatives continue to meet today (although the Constitution states they are to meet in the capitol). The Governor’s office remains in the capitol, though not accessible to the public; rooms open to visitors are the Old Supreme Court Chamber, and the old Senate and House Chambers, now restored to their 19th century appearance.

Past those beautiful staircases and outside again, I wandered the Avenue of Flags, a major feature of the capitol grounds; it was officially dedicated April 6, 1968. The flag of each of the 50 states is on display, arranged in a semi-circle between the portico of the south wing and Washington Avenue. A native stone, engraved with the state name, is set at the base of each flagpole.

Past those beautiful staircases and outside again, I wandered the Avenue of Flags, a major feature of the capitol grounds; it was officially dedicated April 6, 1968. The flag of each of the 50 states is on display, arranged in a semi-circle between the portico of the south wing and Washington Avenue. A native stone, engraved with the state name, is set at the base of each flagpole.

Massive white granite buildings surround the capitol grounds, the State House is far to my left; across Washington Street, where my car is parked, sits the Archives; more stories inside.

Alabama State Capitol, 600 Dexter Avenue, Montgomery, open Monday-Saturday, closed Sunday. Guided tours must be prearranged, 334-242-7100, http://www.preserveala.org/capitoltour.htm