» posted on Tuesday, April 23rd, 2013 by Linda Lou Burton

Ghosts On The Hill

Linda Burton posting from Nashville, Tennessee – The couple behind was panting even more than me. There was a steep hillclimb to get to the capitol entry point and the closest parking was blocks away in an expensive high-rise garage. I passed THP scrutiny and received my entry pass but needed to catch my breath; I watched as the Tennessee Highway Patrol guard at the tunnel door went through his routine again. He opened the woman’s bag and searched it; he photocopied their photo ID and entered their names into his database. Finally issued passes,

Linda Burton posting from Nashville, Tennessee – The couple behind was panting even more than me. There was a steep hillclimb to get to the capitol entry point and the closest parking was blocks away in an expensive high-rise garage. I passed THP scrutiny and received my entry pass but needed to catch my breath; I watched as the Tennessee Highway Patrol guard at the tunnel door went through his routine again. He opened the woman’s bag and searched it; he photocopied their photo ID and entered their names into his database. Finally issued passes,  they were allowed to walk through Xray, and given directions to the elevator. “That’s not very welcoming,” I commented to the officer, noting his name on his badge and adding “Mike,” to my sentence, aiming for a friendly tone. “Why do you require photo ID before allowing people to visit their state capitol? I haven’t seen that anywhere before.” Mike shook his head in a kind of apology. “We’ve had so many threats,” he answered. “We check names against our database of people who are considered dangerous and not allowed in.” We chatted a while, discussing the fine line between “openness” and “safety” with regard to public buildings in this day and age. The Tennessee State Capitol is a treasure, to be sure,

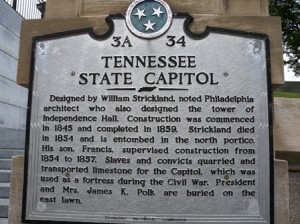

they were allowed to walk through Xray, and given directions to the elevator. “That’s not very welcoming,” I commented to the officer, noting his name on his badge and adding “Mike,” to my sentence, aiming for a friendly tone. “Why do you require photo ID before allowing people to visit their state capitol? I haven’t seen that anywhere before.” Mike shook his head in a kind of apology. “We’ve had so many threats,” he answered. “We check names against our database of people who are considered dangerous and not allowed in.” We chatted a while, discussing the fine line between “openness” and “safety” with regard to public buildings in this day and age. The Tennessee State Capitol is a treasure, to be sure,  filled with historic moments and memories; it even serves as the final resting place of its architect William Strickland, who is buried in the northeast corner. Though sitting high atop a hill, the building is dwarfed today by the city that has grown up around it; skyscrapers and congested streets almost edge out the feel of history. But I’d come to see; I said goodbye to Mike and headed down the hall, my photo-pass stuck to my shirt.

filled with historic moments and memories; it even serves as the final resting place of its architect William Strickland, who is buried in the northeast corner. Though sitting high atop a hill, the building is dwarfed today by the city that has grown up around it; skyscrapers and congested streets almost edge out the feel of history. But I’d come to see; I said goodbye to Mike and headed down the hall, my photo-pass stuck to my shirt.

The tour guides were already touring; I picked up a self-guided brochure from the Visitor Desk and started to read. The cornerstone was laid July 4, 1845, and the final stone July 21, 1855. Additional work was done all the way up to 1859, and of course, renovations and major repairs have taken place since. Painted faces watched me from portraits on the wall; William Strickland, the architect; Samuel Morgan, chairman of the Capitol Building Commission; Andrew Jackson, 7th President of the United States; James K Polk, 11th President; and Andrew Johnson, 17th, all native sons. Look up at the ceiling frescoes, my booklet suggested; an American eagle up above; the State Seal too, and the State Motto, “Agriculture and Commerce.” Tennessee was the 16th state admitted to the Union, in 1796. I passed more watchful portraits – governors this time.

Now I’d reached Point # 12: Move to the north end of the building and enter the open doors on your right. I walked into the Supreme Court Chamber; a pleasant place; cane-back chairs in a row faced heavy-duty leather chairs on the dais; blue drapes on the back wall hung over shuttered windows. “In 1988, the room was restored to the way it looked in the 1850’s” I read. On the far wall from a composite portrait more faces watched; famous Tennesseans, perhaps?

Now I’d reached Point # 12: Move to the north end of the building and enter the open doors on your right. I walked into the Supreme Court Chamber; a pleasant place; cane-back chairs in a row faced heavy-duty leather chairs on the dais; blue drapes on the back wall hung over shuttered windows. “In 1988, the room was restored to the way it looked in the 1850’s” I read. On the far wall from a composite portrait more faces watched; famous Tennesseans, perhaps?

Point #14, Governor’s Reception Room. Computer screens and chandeliers; walnut desks placed against mural-painted walls; the faces of Tennessee. “I’m sure you enjoy working in this beautiful spot,” I commented to the receptionist, “except for the interruptions all day long.” “We don’t mind a bit,” she answered, “please take your time and look around.” The murals were designed and painted by Jirayr Zorthian, I read, when the room was remodeled in 1938. They portray Tennessee history “as viewed in the 1930’s.” The first Tennesseans, the Cherokee. The first European, Hernando de Soto, 1540. The first European building, Fort Prudhomme, 1682. The founding of Nashville, 1779. Nashville during the Capitol construction, 1855. Agriculture, represented by the Hermitage, Andrew Jackson’s home. Commerce, represented by the steamboat. I was feeling really tuned to history now. Time to go upstairs.

Point #14, Governor’s Reception Room. Computer screens and chandeliers; walnut desks placed against mural-painted walls; the faces of Tennessee. “I’m sure you enjoy working in this beautiful spot,” I commented to the receptionist, “except for the interruptions all day long.” “We don’t mind a bit,” she answered, “please take your time and look around.” The murals were designed and painted by Jirayr Zorthian, I read, when the room was remodeled in 1938. They portray Tennessee history “as viewed in the 1930’s.” The first Tennesseans, the Cherokee. The first European, Hernando de Soto, 1540. The first European building, Fort Prudhomme, 1682. The founding of Nashville, 1779. Nashville during the Capitol construction, 1855. Agriculture, represented by the Hermitage, Andrew Jackson’s home. Commerce, represented by the steamboat. I was feeling really tuned to history now. Time to go upstairs.

Point #18, House of Representatives. A professional-looking spot, but pretty too, red drapes over shuttered windows; “single-shaft columns of Nashville limestone rising twenty-two feet ten inches” according to the booklet. Papers were neatly stacked on desks, places for the 99 representatives to work. A very significant moment in national history happened here; the booklet explains:

Point #18, House of Representatives. A professional-looking spot, but pretty too, red drapes over shuttered windows; “single-shaft columns of Nashville limestone rising twenty-two feet ten inches” according to the booklet. Papers were neatly stacked on desks, places for the 99 representatives to work. A very significant moment in national history happened here; the booklet explains:

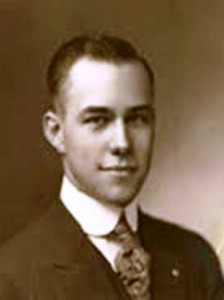

In the House chamber on August 20, 1920, Tennessee became the final state to ratify the 19th Amendment to the US Constitution giving women the right to vote. The House was divided on the issue and the ratification passed by only one vote.

A ghost came out of the corner of the room and whispered to me. It was Harry Burn, wearing a red rose on his lapel. “I did it for my mother,” he said. ““I know that a mother’s advice is always safest for her boy to follow, and my mother wanted me to vote for ratification.” “Good  for you, Harry,” I whispered back. “You did the right thing.” The story of Harry Burn has always been a favorite of mine; he was the youngest member of the legislature, only 24 on that momentous day in 1920. Thirty-five states had already ratified the 19th Amendment, which stated “the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex;” thirty-six states were required. The Amendment sailed through the Tennessee Senate but stalled in the House, prompting thousands of pro- and anti-suffrage activists to descend on Nashville. Harry’s red rose signified his opposition; after a week-long intense debate the House vote ended in a tie. Then Harry got a note from his mother, Phoebe Ensminger Burn, known to her family and friends as Miss Febb. She urged him to “be a good boy.” When the vote was called again, Harry switched his vote to “Aye,” thus ending women’s decades-long quest for the right to vote. Still wearing the red rose and clutching his mother’s note, Harry then fled to the attic and camped there until the maddening anti-crowds downstairs dispersed. Some say he crept onto a third-floor ledge to escape an angry mob of lawmakers who threatened to rough him up! The next day, Harry defended his last-minute reversal in a speech to the assembly, publicly expressing his personal support of universal suffrage, declaring, “I believe we had a moral and legal right to ratify.” Thanks Harry, and thanks Miss Febb.

for you, Harry,” I whispered back. “You did the right thing.” The story of Harry Burn has always been a favorite of mine; he was the youngest member of the legislature, only 24 on that momentous day in 1920. Thirty-five states had already ratified the 19th Amendment, which stated “the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex;” thirty-six states were required. The Amendment sailed through the Tennessee Senate but stalled in the House, prompting thousands of pro- and anti-suffrage activists to descend on Nashville. Harry’s red rose signified his opposition; after a week-long intense debate the House vote ended in a tie. Then Harry got a note from his mother, Phoebe Ensminger Burn, known to her family and friends as Miss Febb. She urged him to “be a good boy.” When the vote was called again, Harry switched his vote to “Aye,” thus ending women’s decades-long quest for the right to vote. Still wearing the red rose and clutching his mother’s note, Harry then fled to the attic and camped there until the maddening anti-crowds downstairs dispersed. Some say he crept onto a third-floor ledge to escape an angry mob of lawmakers who threatened to rough him up! The next day, Harry defended his last-minute reversal in a speech to the assembly, publicly expressing his personal support of universal suffrage, declaring, “I believe we had a moral and legal right to ratify.” Thanks Harry, and thanks Miss Febb.

Point # 23, the Senate. Another dignified room; smaller for the 33 members of the Senate. Green-drapes in here; the original 1855 gasolier overhead; Tennessee marble columns; a spacious visitor gallery above. I got my pictures and headed across the hall.

Point # 23, the Senate. Another dignified room; smaller for the 33 members of the Senate. Green-drapes in here; the original 1855 gasolier overhead; Tennessee marble columns; a spacious visitor gallery above. I got my pictures and headed across the hall.

Point # 26, the Library. An original spiral staircase, ordered from a catalogue, leading up to dusty books now there for show, in this room restored to its mid-19th century look. Portraits and busts surrounded me, famous figures of writers and politicians;  William Shakespeare, Dante, John Milton; George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson. Andrew Jackson and Rachel Jackson, on the far wall, I’d like to stay and talk; to Rachel in particular. But time to go; I headed out.

William Shakespeare, Dante, John Milton; George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson. Andrew Jackson and Rachel Jackson, on the far wall, I’d like to stay and talk; to Rachel in particular. But time to go; I headed out.

“I didn’t shoot at them,” said a whispered voice from beside the marble stairs. “I was only trying to scare them.” Another ghost was speaking; he pointed to the marble handrail. I saw the scar where it was chipped by a bullet; I’d heard the story once before. “It turned out fine,” I whispered back. “You  did a good thing.” “I guess I did,” he said, cocking his head sideways and nodding before he faded away. “I guess I did.”

did a good thing.” “I guess I did,” he said, cocking his head sideways and nodding before he faded away. “I guess I did.”

The story. Tennessee was the last southern state to secede from the Union and join the Confederacy; #11 on June 24, 1861. Nashville was an immediate target due to its Cumberland River port; it fell to Union forces early in 1862 and Andrew Johnson set up headquarters in the capitol. Right here, I thought; I’d like to meet his ghost too. The scar on the rail came after the Civil War; it happened July 19, 1866 during a bitter fight in the Legislature over the ratification of the 14th Amendment. The Tennessee legislature had already approved an amendment to its state constitution prohibiting slavery (February 22, 1865) and had ratified the 13th Amendment to the US Constitution abolishing slavery in every state (April 7, 1865). The 14th Amendment granting the rights of citizenship to African Americans was passed by the US Congress as of June 16, 1866 and headed to the states for ratification. Connecticut was first to ratify, then New Hampshire. In the Tennessee legislature those who opposed ratification knew they didn’t have enough votes to block passage, so on that warm July day they decided to leave so there would not be a quorum. The armed guard standing by was ordered to fire; he aimed down the stairs ahead of the fleeing men. The men turned and ran back to their seats; the 14th Amendment was ratified; and Tennessee became the first Confederate state to rejoin the Union; it was the only southern state that did not have a military governor during the Reconstruction period.

Ghosts, everywhere. Presidents and governors, the troubled and the brave. Harry Burn; an unnamed guard; people whose split-second decisions changed history. I walked the long tunnel hall to the exit where Mike was just ending his shift. “Did you enjoy your visit to the capitol?” he asked. “It was enlightening,” I answered. I didn’t mention the ghosts, since they didn’t have a pass.

Tennessee State Capitol http://www.capitol.tn.gov/about/capitolvisit.html