» posted on Monday, November 30th, 2015 by Linda Lou Burton

Pioneers and Pilgrimages

Linda Burton posting from Arkadelphia, Arkansas – I bought two figures at Hobby Lobby a few months back. One is a dark-skinned woman with plaited hair, her black braids draped over her shoulders atop a fringed shawl; the other a fair-skinned woman with slightly reddish hair, cut shoulder length, the hood of her shawl softly framing her face. Native American? Scotch-Irish? Wearing finely tanned animal skins and finely stitched linen? Both are carrying baskets filled with food – pumpkins, squash, apples, grapes. Both are beautiful, and serene. “The spirit of Thanksgiving,” I thought when I spotted them. “My heritage, and just right for the November dining table.” I added gourds from the grocery; odd-shaped greens and yellows; plus several round ones tinged with orange. Brother was coming for most of Thanksgiving week; coming to this place we’d found together by an accident of fate. Have I told you this before? The Journal? The Search? The Arkansas tragedy?

Linda Burton posting from Arkadelphia, Arkansas – I bought two figures at Hobby Lobby a few months back. One is a dark-skinned woman with plaited hair, her black braids draped over her shoulders atop a fringed shawl; the other a fair-skinned woman with slightly reddish hair, cut shoulder length, the hood of her shawl softly framing her face. Native American? Scotch-Irish? Wearing finely tanned animal skins and finely stitched linen? Both are carrying baskets filled with food – pumpkins, squash, apples, grapes. Both are beautiful, and serene. “The spirit of Thanksgiving,” I thought when I spotted them. “My heritage, and just right for the November dining table.” I added gourds from the grocery; odd-shaped greens and yellows; plus several round ones tinged with orange. Brother was coming for most of Thanksgiving week; coming to this place we’d found together by an accident of fate. Have I told you this before? The Journal? The Search? The Arkansas tragedy?

It’s a story of our country really; our own personal connection to thousands of stories of the great westward migration, stories of pioneers, of courage, and change. Ours centers on a little girl named Martha Jane, who rolled through Clark County, Arkansas in November 1849 at the tender age of four. What an adventure! Her grandpa, a widower by then, rode feistily ahead  on horseback, her Papa did too. Papa was William Irwin Jr, a Baptist preacher leading the group from Alabama to Texas to start a new settlement in the new state. Mama was Susy Ann, the soul of sweetness, who rode in the wagon cradling little baby Caroline in her arms. Brother Howell was two, and often rode in the other wagon with cousin Joseph, who was the same age. Big sister Elizabeth was six and a real “mother’s helper,” watching over Martha Jane as the two walked alongside the wagon, often running ahead when they spotted another wagon, or a creek they’d have to ford. It was exciting as the

on horseback, her Papa did too. Papa was William Irwin Jr, a Baptist preacher leading the group from Alabama to Texas to start a new settlement in the new state. Mama was Susy Ann, the soul of sweetness, who rode in the wagon cradling little baby Caroline in her arms. Brother Howell was two, and often rode in the other wagon with cousin Joseph, who was the same age. Big sister Elizabeth was six and a real “mother’s helper,” watching over Martha Jane as the two walked alongside the wagon, often running ahead when they spotted another wagon, or a creek they’d have to ford. It was exciting as the  wagons eased down the bank and the horses splashed through the shallow stream. Bigger creeks meant a ride on a ferry! They crossed two big rivers that way – the Mississippi River at Memphis; the Arkansas River at Little Rock.

wagons eased down the bank and the horses splashed through the shallow stream. Bigger creeks meant a ride on a ferry! They crossed two big rivers that way – the Mississippi River at Memphis; the Arkansas River at Little Rock.

Evenings around the campfire were a busy time; Grandpa and Uncle Matthew and young Wiley and Sampson tended the horses while Papa and Uncle Benejah checked the wagons and made any repairs that were needed before dark. Uncle Reuben and Aunt Martha got the campfires going and the supper started, with Penney’s help. Mama and Aunt Amanda looked after the five children, making a home out of another night on the trail. Sixteen people – did you count? William Irwin Sr, William Irwin Jr and his wife, Susy Ann Herring Irwin and their four children – Elizabeth, Martha Jane, Howell, Caroline. Susy Ann’s brother Benejah Herring and his wife Amanda McDowell Herring, their son Joseph, and Amanda’s teen brother Wiley. Susy Ann’s unmarried brother Matthew Herring, and her newly married sister Martha Herring Johnson, and Martha’s husband Reuben Johnson. That totals fourteen family members; now add the slaves Sampson and Penney, who grinned and nodded yes when asked if they’d be willing to leave the Herring farm where they were born to join the adventuring party headed for Texas. Two wagons, eight horses, sixteen people. They never made it.

Between November 14 and November 26, 1849, ten of them died. Grandpa was first. According to William’s Journal, in which he recorded every creek crossed and mile traveled, they were somewhere between Hollywood and Antoine, Arkansas when cholera struck; the last Journal entry is simply “Father died about….” It must have been pure bedlam, a hellish nightmare from that point forward. Cholera was an unknown and it was fast; painful cramps and diarrhea; all body fluids gone; system shutdown; death in hours. There were no cell phones, no EMT’s, no stopping this miserable water-born stalker that probably came from one of the Arkansas creeks they’d crossed and got their evening water from. Nobody  understood water purification in those days; in fact cholera epidemics were sweeping the nation in 1849. In crowded cities water wells were generally located next to the outdoor privy. Cholera claimed thousands as people prayed and lit fires thinking the smoke would purify the air. But it wasn’t the air.

understood water purification in those days; in fact cholera epidemics were sweeping the nation in 1849. In crowded cities water wells were generally located next to the outdoor privy. Cholera claimed thousands as people prayed and lit fires thinking the smoke would purify the air. But it wasn’t the air.

We have copies of letters Martha and Susy Ann wrote to their father back in Alabama, telling of their plight. From Martha: “Old man Irwin died about midnight. Friday morning, brother Benejah and on the same day Sampson. Sunday morning about daybreak, brother Matthew, Sunday night between midnight and day brother William, and Joseph, in an hour of each other. Tuesday night about midnight my dear and most affectionate companion.” From Susy Ann: “All our menfolk have died; all my children are sick but Elizabeth Ann; Howell is almost dead; I do not know how long any of us will be alive.”

Howell and Elizabeth died after the letter was written; then the last, baby Caroline, on November 26. Survivors were Susy Ann, age 26, and daughter Martha Jane, age 4; Amanda, age 22 and her brother Wiley, age 15; Martha age 19; Penney age unknown. Susy Ann buried her father-in-law, her husband and three of her children, two brothers and one brother-in law, her nephew, and the sturdy Sampson over the course of twelve days. Amanda buried her husband and her son. Both women were pregnant, did I mention that? Pregnant, and grieving; likely ill themselves; certainly in shock. It took two months for the rescue party to arrive and get them safely back to Alabama. That’s where Martha Jane grew up, and married, and gave birth to twelve children.  Her first-born was my great-grandmother Mary Susan, Grandma Burton to me, who made a quilt for my 16th birthday that hangs on my quilt rack today.

Her first-born was my great-grandmother Mary Susan, Grandma Burton to me, who made a quilt for my 16th birthday that hangs on my quilt rack today.

Grandma Burton had a son named James – my grandfather; then there was my Dad; then my brother and me. What can I say? Connecting to one’s past is a powerful strengthener. Brother and I made our 2008 pilgrimage to Arkansas in hopes of locating those 1849 graves. We found what could be their graves – the numbers match and the location is plausible. The fieldstones marking head and foot are nameless, but that’s all right; we love the meaning of it; we love the possibility. If other pioneers are buried in those ten wooded graves instead, we love them too.

I had flowers in the church on November 22 with this message: in memory of the ten ancestors who died along the trail in Clark County in November 1849 traveling from Alabama to Texas during the great westward migration. And brother brought flowers to leave behind in the cemetery –neon-orange to brighten up the woods. It was raining when we arrived at Clear Springs and rained harder as the day wore on. How do you clear off graves  with an umbrella in one hand? We laughed it off, donned heavier jackets; this was nothing compared to those November days of 1849.

with an umbrella in one hand? We laughed it off, donned heavier jackets; this was nothing compared to those November days of 1849.

Back at the house, I made a steaming pot of vegetable soup and some crispy hot cornbread as the rain continued to fall. We sat at the computer and looked at our pictures – the ones taken a day earlier, when we found a spot on the Ouachita River near Rockport that looked shallow enough for wagons to cross and matches William’s Journal entry; the ones of DeRoche Creek  near Friendship by the Clark County line where the Southwest Trail came through. We looked again at all the photos we took in 2008, when we first followed William’s Journal notations and came to Arkansas, a trip that prompted my move here in 2013 to keep looking for answers.

near Friendship by the Clark County line where the Southwest Trail came through. We looked again at all the photos we took in 2008, when we first followed William’s Journal notations and came to Arkansas, a trip that prompted my move here in 2013 to keep looking for answers.

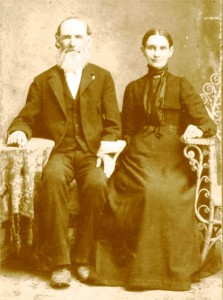

On the wall above the piano hangs a picture of Martha Jane, not as a traumatized little girl, but as a dignified married lady, peacefully seated beside her husband James, her hand laid gently across his arm. “No Martha Jane, your family is not forgot,” I tell her, almost every day.