‘US Presidential Bios’ Category

» posted on Sunday, July 21st, 2024 by Linda Lou Burton

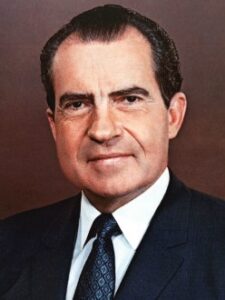

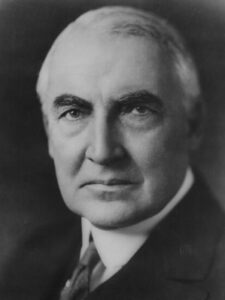

#37. Nixon, Richard Milhous

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas –Richard Milhous Nixon (1913 – 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, from 1969 to 1974. And he was the only president escorted out of the White House before his term was up. Remember that story about George Washington and the cherry tree? It was a made-up tale, making the point that George was such an honest and honorable fellow that even when he did a terrible thing – that is, he cut down their prize cherry tree with the little hatchet his father entrusted to him – his remorse was so great he said “Father, I cannot tell a lie. It was me that did it.” I just rewatched the tapes of the “Nixon Resignation Speech” of August 8, 1974; you can too, it’s all out there. But you won’t see remorse. You can watch his exit on August 9 too;  just after the swearing-in of new president Gerald Ford. It’s weirdly sad; the White House backdrop; the red-carpet path lined with all branches of the military, arms at present; he smiles as he walks past. The now excused First Lady Pat Nixon clings to new First Lady Betty Ford, who is clinging to our new President Gerald Ford; all three have a somber look. The Nixons board the helicopter, and Richard turns. Then, arms flung high, he gives the crowd his trademark V.

just after the swearing-in of new president Gerald Ford. It’s weirdly sad; the White House backdrop; the red-carpet path lined with all branches of the military, arms at present; he smiles as he walks past. The now excused First Lady Pat Nixon clings to new First Lady Betty Ford, who is clinging to our new President Gerald Ford; all three have a somber look. The Nixons board the helicopter, and Richard turns. Then, arms flung high, he gives the crowd his trademark V.

On September 8 Gerald Ford issued Proclamation 4311, granting a full and unconditional pardon to Richard Nixon for any crimes he might have committed against the United States. Richard Nixon was absolved of any connection to the infamous Watergate Scandal; 69 others were charged with various connected crimes; 48 were found guilty and were fined, or served time in prison. Richard Nixon lived another twenty years, assuming, in his own mind at least, the role of “elder statesman.” But what about the cherry tree?

Cute Kid

Richard Milhous Nixon was born in Yorba Linda, California January 9, 1913, the second of the five sons of Francis and Hannah Milhous Nixon. The name of the town goes back – Yorba was the family name on the original Spanish land grant; Linda simply means “pretty.” And it was pretty, an agricultural area of lemon groves southeast of Los Angeles; father Francis built the house on their little ranch. Hannah was of Quaker faith, and the boys were influenced by Quaker observances, such as abstinence from alcohol, dancing, and swearing. “We were poor,” Richard once explained to Eisenhower, “but the glory of it was we didn’t know it.” Their ranch failed in 1922; the family moved to Whittier, another area with many Quakers, and Francis opened a grocery store and gas station.

Richard Milhous Nixon was born in Yorba Linda, California January 9, 1913, the second of the five sons of Francis and Hannah Milhous Nixon. The name of the town goes back – Yorba was the family name on the original Spanish land grant; Linda simply means “pretty.” And it was pretty, an agricultural area of lemon groves southeast of Los Angeles; father Francis built the house on their little ranch. Hannah was of Quaker faith, and the boys were influenced by Quaker observances, such as abstinence from alcohol, dancing, and swearing. “We were poor,” Richard once explained to Eisenhower, “but the glory of it was we didn’t know it.” Their ranch failed in 1922; the family moved to Whittier, another area with many Quakers, and Francis opened a grocery store and gas station.

Richard did well in school; he was president of his eight-grade class; in high school he played junior varsity football and had great success as a debater, winning several championships. All this while helping at the family store – up at 4 am, drive to Los Angeles to purchase vegetables at the market, back to the store to wash and display them; then on to school. He graduated from Whittier High third in his class of 207. And he was offered a tuition grant for Harvard! His older brother Harold was ill, his mother needed help and he was needed at the store, so he stayed at home and enrolled at Whittier College, graduating summa cum laude with a BA in history in 1934. And then a scholarship to Duke University School of Law. There was intense competition for scholarships there; he kept his all the way through, was elected president of the Duke Bar Association, and graduated third in his class in June 1937.

Right now, I’m liking Richard Nixon a lot, aren’t you?

All Grown Up

Admitted to the California bar in 1937, Richard went to work as a commercial litigator for  local petroleum companies; the next year, he met Pat. Thelma Ryan, that is, his future wife. A funny circumstance, they were cast in a play opposite one another. He claimed “love at first sight”; they didn’t marry however until June 21, 1940. Daughter Tricia was born in 1946, Julie in 1948. We’ll get back to them.

local petroleum companies; the next year, he met Pat. Thelma Ryan, that is, his future wife. A funny circumstance, they were cast in a play opposite one another. He claimed “love at first sight”; they didn’t marry however until June 21, 1940. Daughter Tricia was born in 1946, Julie in 1948. We’ll get back to them.

As a birthright Quaker Richard could have  claimed exemption from the draft, but sought a commission in the US Navy. He served in numerous capacities throughout WWII and received numerous commendations; he was relieved of active duty in 1946. Now here’s a tidbit for you: remember Eisenhower’s passion for bridge? Richard picked up five-card stud poker during the war; his winnings helped to finance his first congressional campaign. And where was that? Well, back in Whittier, of course, where he was still a registered voter. In 1947, at the age of 34, he was elected as a US Representative from California . Then 1950-53 a US Senator from California; then off to Washington as Eisenhower’s VP from 1953-1961. So far, doing great, a winning streak. Obviously, President next?

claimed exemption from the draft, but sought a commission in the US Navy. He served in numerous capacities throughout WWII and received numerous commendations; he was relieved of active duty in 1946. Now here’s a tidbit for you: remember Eisenhower’s passion for bridge? Richard picked up five-card stud poker during the war; his winnings helped to finance his first congressional campaign. And where was that? Well, back in Whittier, of course, where he was still a registered voter. In 1947, at the age of 34, he was elected as a US Representative from California . Then 1950-53 a US Senator from California; then off to Washington as Eisenhower’s VP from 1953-1961. So far, doing great, a winning streak. Obviously, President next?

Sometimes You Lose

Maybe he was just too sure of himself. Sometimes a long winning streak makes us lazy. Or maybe he was sick that day; everyone has a bad day now and then. But that first debate with John Kennedy was a bummer for Richard, who had long ago proven himself a great debater – he had all those certificates from high school and college to prove it. Maybe too many strings got pulled during that 1960 campaign, and merit lost out to craftiness? With television now a factor, maybe it hadn’t occurred to any of us yet that image would actually become more important than substance.

A squeaky close defeat is worse than a landslide whuppin’; you wonder what else you could have done, or where things went wrong. There were charges of voter fraud, but in January 1961 at the end of term, the Nixons moved back to California and Richard wrote a book. It was a best seller.

So everybody said run for governor of California, and he did. And he lost. Pretty clear, this was the end of Richard Nixon’s career, according to the media. On November 7, 1962, the morning after the election, Richard made an impromptu speech, saying “You won’t have Nixon to kick around anymore because, gentlemen, this is my last press conference.”

If I were a reader of minds, I’d point to that as the moment when Richard Nixon took advice from Robert Johnson, out there on Mississippi’s Highway 61. If you don’t know your blues history, look up that part about making deals with the devil.

Feeling Out The Way

In 1963 the Nixons traveled Europe; Richard gave press conferences there, and met with leaders of the countries visited. They moved to New York, where Richard joined a leading law firm. In 1964, he received some write-in votes in the primaries; but he stayed quiet. The Republicans had heavy losses.

At the end of 1967, Richard told his family he planned to run for president a second time. In March 1968, President Johnson announced he would not be running again. In April Martin Luther King Jr was assassinated. In June, Robert Kennedy was assassinated while campaigning. In August, at the Republican Convention in Miami, Richard was nominated on the first ballot and chose Spiro Agnew, governor of Maryland, as his VP.

We had a three-way race: George Wallace as an Independent to pacify the southern states who now hated the Democrats due to the recent civil rights legislation; Hubert Humphrey for the Democrats, who were blamed for all the turmoil and upheaval going on – war and anti-war demonstrations; the hippie counterculture, assassinations, everything in the country that was bad; and Richard Nixon, who promised “peace with honor” and whose slogan was “Nixon’s the One.” Who would you have voted for? I voted for Nixon, he represented sanity in an insane time. I had teen-age sons, and prayed for war to end. And so did just enough people. Former VP Richard Nixon, and former Second Lady Pat, were now sitting on top. Richard sent a note to Hubert, saying, “I know how it hurts to lose a close one.”

Let’s Talk About Pat

You’ll need to get out your yellow pad to take notes about Pat Nixon. Just an ordinary gal, but a superstar in her own sweet way. You’ll see what I mean. Thelma Catherine Ryan (1912-1993) was born March 16, 1912 in the small mining town of Ely, Nevada, the third child of William and Katherine Halberstadt Ryan. Her father nicknamed her “Pat” because she was born just minutes before St Patrick’s Day; it stuck. Father William was a miner, then the family moved to California in 1914 and settled on a small truck farm. Pat’s mother died when she was 12, her father 5 years later; Pat assumed the household duties for her older brothers William and Thomas. She also worked at a local bank as a janitor and bookkeeper during that time.

You’ll need to get out your yellow pad to take notes about Pat Nixon. Just an ordinary gal, but a superstar in her own sweet way. You’ll see what I mean. Thelma Catherine Ryan (1912-1993) was born March 16, 1912 in the small mining town of Ely, Nevada, the third child of William and Katherine Halberstadt Ryan. Her father nicknamed her “Pat” because she was born just minutes before St Patrick’s Day; it stuck. Father William was a miner, then the family moved to California in 1914 and settled on a small truck farm. Pat’s mother died when she was 12, her father 5 years later; Pat assumed the household duties for her older brothers William and Thomas. She also worked at a local bank as a janitor and bookkeeper during that time.

While attending Fullerton College, she worked as a driver, pharmacy manager, telephone operator and typist. In 1931 she enrolled at the University of Southern California and supplemented her income as a sales clerk, typing teacher, and an extra in the film industry. Yes, she had bit parts in a few motion pictures. But what she wanted was teaching; and in 1937 she graduated cum laude from USC with a BS in merchandising, and a teaching certificate. She took a position at Whittier High School. Ah. And then the part in the play, and meeting Richard, and getting married, and becoming a mom. And the wife of a politician. She campaigned. As Second Lady, and then as First, she undertook missions of goodwill around the world. She

While attending Fullerton College, she worked as a driver, pharmacy manager, telephone operator and typist. In 1931 she enrolled at the University of Southern California and supplemented her income as a sales clerk, typing teacher, and an extra in the film industry. Yes, she had bit parts in a few motion pictures. But what she wanted was teaching; and in 1937 she graduated cum laude from USC with a BS in merchandising, and a teaching certificate. She took a position at Whittier High School. Ah. And then the part in the play, and meeting Richard, and getting married, and becoming a mom. And the wife of a politician. She campaigned. As Second Lady, and then as First, she undertook missions of goodwill around the world. She  didn’t stand and wave; she visited people on their home ground – schools, orphanages, hospitals, markets. She was the most traveled First Lady in US history (later surpassed by Hillary Clinton); she made solo trips to Africa and South America as “Madam Ambassador”; in Vietnam she entered a combat zone, lifting off in an open-door helicopter to witness US troops fighting in the jungle below; she visited Army hospitals, speaking with every patient there.

didn’t stand and wave; she visited people on their home ground – schools, orphanages, hospitals, markets. She was the most traveled First Lady in US history (later surpassed by Hillary Clinton); she made solo trips to Africa and South America as “Madam Ambassador”; in Vietnam she entered a combat zone, lifting off in an open-door helicopter to witness US troops fighting in the jungle below; she visited Army hospitals, speaking with every patient there.

Pat did things for the White House to make it prettier, and more useful, as many First Ladies devoted their time to, but she did down-to-earth things too; her first Thanksgiving in the White House she organized a meal for 225 senior citizens who didn’t have families; the next year she invited wounded servicemen to the White House for Thanksgiving dinner. She ordered pamphlets for visitors describing the rooms of the house in English, Spanish, French, Italian, and Russian. She had ramps installed for the handicapped and instructed the police who served as tour guides to “learn how” by attending sessions at the Winterthur Museum. Guides were to speak slowly and directly to deaf groups; it was ordered that the blind be allowed to touch antiques. Just little things like that.

And Then There Was Watergate

You’ll have to dig into the Watergate Scandal on your own. Basically, as plans began for the 1972 campaign, some folks from the CRN (Committee to Reelect Nixon) broke into the DNC headquarters (Democratic National Committee). To “get the jump,” you know. And they got caught. And they lied. And lots of people had to lie to cover up those lies. One of those was our president. Even though Richard Nixon won in 1972 with 61% of the popular vote and 97% of the electoral, the devil tiptoed in and began to claim his due.

The swamp muck of Watergate. The public ousting. The helicopter ride. Richard wrote nine books over the next 20 years; he and Pat traveled a great deal, always representing the United States, until their health began to fail. Pat died June 22, 1993 at their home in New Jersey at age 81 of cancer and emphysema; Richard and their daughters were with her. Richard lived another ten months, suffering a severe stroke in his home; he died April 22, 1994 at the age of 81; his daughters were there for him too.

Richard and Pat are buried on the grounds of the Nixon Library and Museum in Yorba Linda, California; his birthplace is part of the overall site.

As to my party with the Nixons, yes, I would have enjoyed being with them in their early married days; they were hard workers with good dreams. But the swamp-muck Nixon, no. My youngest son, who was only 9 the day we listened to that 1974 Resignation Speech, has this advice for his sons, and nieces, and nephews concerning life: Always take responsibility for your actions. If you mess up, admit it, and try to make things right.

Even if you’ve chopped down the cherry tree.

» posted on Saturday, July 20th, 2024 by Linda Lou Burton

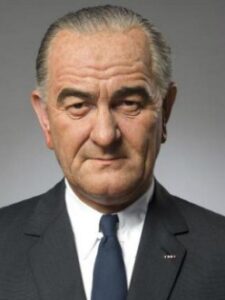

#36. Johnson, Lyndon Baines

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – Lyndon Baines Johnson (1908-1973) was the 36th President of the United States, from 1963-1969. Looking back over the previous 35, it seems the US populace tends to select presidents “seasonally”; that is, in a longing for change (like when we chose George the ordinary man over George the king). When it’s spring we can’t wait for summer; in August heat we long for the coolness of fall. One party’s policies we replace with the other; and then, we change back. But that move from a youthful rock star to a good old boy in a cowboy hat was a same-party insta-switch. Of course, “different” was the plan, the Democratic ticket had needed a southerner to balance New England cool, and entice the southern states to stay on board. Lyndon obliged. VP Lyndon was in the second car behind John Kennedy in that fatal Texas parade November 22, 1963; he and Lady Bird were scheduled to host the Kennedys for a weekend  of relaxation at their Texas ranch after campaigning was done. Lyndon took care of Jackie’s wishes immediately after John’s death; he made sure she was standing by his side as he was sworn in on Air Force One. As our new president, he dictated that even though the Secret Service wanted them back in Washington immediately – who knew what plots were afoot?; and even though Texas medical examiners insisted an autopsy be performed there; the dead president’s body was put onto Air Force One and taken to Bethesda Naval Hospital, which was Jackie’s choice. Lyndon was an imposing figure, and he knew how to push.

of relaxation at their Texas ranch after campaigning was done. Lyndon took care of Jackie’s wishes immediately after John’s death; he made sure she was standing by his side as he was sworn in on Air Force One. As our new president, he dictated that even though the Secret Service wanted them back in Washington immediately – who knew what plots were afoot?; and even though Texas medical examiners insisted an autopsy be performed there; the dead president’s body was put onto Air Force One and taken to Bethesda Naval Hospital, which was Jackie’s choice. Lyndon was an imposing figure, and he knew how to push.

Life On The Pedernales

Lyndon Baines Johnson was born August 27, 1908, in a small farmhouse near the Pedernales River in Stonewall, Texas. That was isolated Hill Country, where “the soil was so rocky it was hard to make a living from it.” He was the eldest of the five children of Samuel Ely and Rebekah Baines Johnson – Lyndon, Sam Houston, Rebekah, Josefa, and Lucia. Father Sam served six terms in the Texas Legislature; by the time Lyndon was 10 he was going to the Capitol in Austin with his Dad; he watched the floor debates; he listened to behind-the-scenes deal-making. Rebekah had big dreams for her children; her dreams for Lyndon were especially grand, something she never let him forget.

Lyndon Baines Johnson was born August 27, 1908, in a small farmhouse near the Pedernales River in Stonewall, Texas. That was isolated Hill Country, where “the soil was so rocky it was hard to make a living from it.” He was the eldest of the five children of Samuel Ely and Rebekah Baines Johnson – Lyndon, Sam Houston, Rebekah, Josefa, and Lucia. Father Sam served six terms in the Texas Legislature; by the time Lyndon was 10 he was going to the Capitol in Austin with his Dad; he watched the floor debates; he listened to behind-the-scenes deal-making. Rebekah had big dreams for her children; her dreams for Lyndon were especially grand, something she never let him forget.

So here’s a story-book fairy tale for you: Ludwig Erhard, the chancellor of what was then West Germany, was scheduled to meet with President Kennedy in Washington November 25, 1963, complete with full military honors and a formal black-tie dinner. Instead, he wound up attending the funeral of President Kennedy. The nation-to-nation talk was rescheduled to December, and new President Johnson decided that instead of the Washington DC formality, he’d do the honors in his home state, in his own way. Lyndon met the chancellor at the Austin airport; helicopters flew the party over the state capitol, and then headed for Hill Country and the LBJ Ranch, there along the Pedernales. Secretary of State Dean Rusk was there; diplomatic talks began at the Texas White House but soon shifted to a tour of the ranch. On Sunday there was a visit to nearby Fredericksburg, an area originally settled by German farmers; the Mayor’s welcoming speech was in German; then they went to church, where hymns were sung in German.

The state dinner took place in the high school gymnasium; 30 tables set up on the basketball  court, loaded with five hundred pounds of brisket, three hundred pounds of spareribs, German potato salad, Texas coleslaw, ranch baked beans, and sourdough biscuits. At the end, a choral group sang Tief in Dem Herzen Von Texas (Deep in the Heart of Texas) and a smiling Erhard was presented with a ten-gallon hat. A key relationship with a crucial Cold War ally – solid.

court, loaded with five hundred pounds of brisket, three hundred pounds of spareribs, German potato salad, Texas coleslaw, ranch baked beans, and sourdough biscuits. At the end, a choral group sang Tief in Dem Herzen Von Texas (Deep in the Heart of Texas) and a smiling Erhard was presented with a ten-gallon hat. A key relationship with a crucial Cold War ally – solid.

There’s another part of this story, equally fairy-tellable; on a cross-country move in 1999 I spent a night in Fredericksburg; I went to that church on Sunday morning where hymns are sung in German; then I took the trolley-train-tour around the town, which drove us by that farmhouse where Lyndon was born 91 years before. Our tour guide took great delight in recounting this part of Erhard’s visit: “When they came by here,” he said, “Lyndon poked him in the ribs and grinned, saying ‘Now there’s where I got spermed!’” We laughed; I’m sure Erhard must have too – two guys, cracking jokes. Nothing fancy.

From There, To There

In 1924, Lyndon graduated from Johnson City High School as president of his six-member senior class. And he didn’t want to go to college. He and some friends drove to California and took some odd jobs; then back to Texas and work on a construction crew. Finally, he enrolled at Southwest Texas State Teachers College, where he worked as a janitor and office helper to help cover costs. He left for a year to teach 5th, 6th, and 7th grades at Welhausen, an impoverished  Mexican-American school in the South Texas town of Cotulla. That’s where “purpose” began to take hold and he began to realize the importance of education; finally with enough money to finish school, he graduated in 1930 with a BS in history and a teaching certificate. Just thirty-three more years till the presidency. Lyndon went from teacher to congressional aide; then US Representative from Texas, then Senator from Texas. In 1951 he was Senate Majority whip; in 1954 majority leader. And he tried for the president’s spot on the Democratic ticket in the 1960 election, but lost out to Kennedy.

Mexican-American school in the South Texas town of Cotulla. That’s where “purpose” began to take hold and he began to realize the importance of education; finally with enough money to finish school, he graduated in 1930 with a BS in history and a teaching certificate. Just thirty-three more years till the presidency. Lyndon went from teacher to congressional aide; then US Representative from Texas, then Senator from Texas. In 1951 he was Senate Majority whip; in 1954 majority leader. And he tried for the president’s spot on the Democratic ticket in the 1960 election, but lost out to Kennedy.

Crude, Rude, and Shrewd

Nevermind, I’ll just be an innocuous VP. Shrewd. But Lyndon didn’t behave like a VP was supposed to behave. He requested his own office and full-time staff in the White House; he drafted an executive order for Kennedy’s signature granting him “general supervision” over matters of national security. Kennedy turn him down on both requests, but tried to keep him happy, saying “He knows every reporter in Washington, I can’t afford him saying we’re screwed up.” Bobby was openly contemptuous of Lyndon, that’s Attorney General Robert Kennedy, you know, John’s younger brother. Many members of the Kennedy White House ridiculed Lyndon’s crudeness. Rude.

So Kennedy appointed him head of the President’s Committee on Equal Employment Opportunities (intended as a nominal position) , where Lyndon worked with African Americans and other minorities. To keep him out of the way, Lyndon was sent on many minor diplomatic missions; this gave him insight into global issues (and opportunities for self-promotion). Kennedy gave him control over all presidential appointments involving Texas; and appointed him Chairman of the National Aeronautics and Space Council, asking him to evaluate the US space program and recommend a project that would beat the Soviets. Lyndon recommended getting an American to the moon in the 60s. Fingers in nearly every pie.

High Society to Great Society

With all the dominoes Lyndon managed to row up during his 1,063 days as Vice President, on November 3, 1964, after 347 days as President, they all fell in his direction. It was a landslide win, the largest share of the popular vote for Democrats in history – 61%. He squeaked in as a VP on that Kennedy ticket, but the Texan won his own presidency Texas style. Big.

And so the Great Society was launched. All aimed at expanding civil rights, public broadcasting, access to health care, aid to education and the arts, urban and rural development, and public services. The War on Poverty. Medicare and Medicaid. The Higher Education Act. The Nationality Act. Containment of Communism. And then the ongoing Vietnam War began to spark angry protests. Race riots became violent; crime rates spiked; Lyndon’s approval rating dropped. In despair he chose not to seek another term.

On January 20, 1969, Lyndon Johnson was there for Richard Nixon’s swearing-in, then leaving the White House in Republican hands, got on the plane to fly back to his ranch in Texas. When the front door of the plane closed, he lit a cigarette — his first since his heart attack in 1955. One of his daughters pulled it out of his mouth and said, “Daddy, what are you doing? You’re going to kill yourself.” He took it back and said, “I’ve raised you girls. I’ve been President. Now it’s my time.” On January 22, 1973, at the age of 64, he suffered his final heart attack. He managed to call the Secret Service agents there on the ranch; they found him in his bed, still holding the phone. He is buried near the house where he was born, now a part of the National Park Service.

Historian Kent Germany summarizes the presidency of Lyndon Johnson in this way: The man who was elected to the White House by one of the widest margins in US history and pushed through as much legislation as any other American politician now seems to be remembered best by the public for succeeding an assassinated hero, steering the country into a quagmire in Vietnam, cheating on his saintly wife….”

His Saintly Wife

Claudia Alta Taylor (1912-2007) was born December 22, 1912, in Karnack, Texas, near the Louisiana state line. Her birthplace was “The Brick House,” an antebellum plantation house on the outskirts of town. When  she was a baby, her

she was a baby, her  nursemaid said she was “pretty as a ladybird” and the name stuck. Her father was Thomas Jefferson Taylor; he owned 15,000 acres of rich cotton bottomland and two general stores. Her mother, Minnie Lee Pattillo Taylor, a tall, eccentric woman from an aristocratic Alabama family, fell down a flight of stairs while pregnant and died when Lady Bird was five; her widowed father married two more times. Lady Bird was raised by her maternal aunt Effie Pattillo and spent summers with her Pattillo relatives in Alabama, growing up with watermelon cuttings, and picnics; family gatherings on lazy Sunday afternoons.

nursemaid said she was “pretty as a ladybird” and the name stuck. Her father was Thomas Jefferson Taylor; he owned 15,000 acres of rich cotton bottomland and two general stores. Her mother, Minnie Lee Pattillo Taylor, a tall, eccentric woman from an aristocratic Alabama family, fell down a flight of stairs while pregnant and died when Lady Bird was five; her widowed father married two more times. Lady Bird was raised by her maternal aunt Effie Pattillo and spent summers with her Pattillo relatives in Alabama, growing up with watermelon cuttings, and picnics; family gatherings on lazy Sunday afternoons.

She was 22 when she met Lyndon on a visit to Washington in 1934, and already had herself two degrees from the University of Texas (history and journalism, with honors) and a substantial inheritance from her mother’s estate. Lyndon proposed on their first date. Ten weeks later they married at St Mark’s Episcopal Church in San Antonio.

She was 22 when she met Lyndon on a visit to Washington in 1934, and already had herself two degrees from the University of Texas (history and journalism, with honors) and a substantial inheritance from her mother’s estate. Lyndon proposed on their first date. Ten weeks later they married at St Mark’s Episcopal Church in San Antonio.

Their marriage suffered due to Lyndon’s numerous affairs; her personal writings mention her humiliation over her husband’s infidelities; he often bragged that he “slept with more women than Kennedy did.” But Lady Bird took $10,000 from her inheritance to finance Lyndon’s first campaign when he decided to run for Congress; and Lady Bird ran his congressional office when he enlisted in the Navy at the beginning of WWII.

During WWII, she spent $17,500 from her inheritance to purchase KTBC, an Austin radio station, setting up the LBJ Holding Company with herself as president. In 1952 she added a television station; when Lyndon objected, she reminded him that she could do what she pleased with her inheritance. Eventually, her initial investment turned into more than $150 million for LBJ Holding; she was the first president’s wife to be a millionaire in her own right before her husband was elected to office. Well then.

When All Is Said And Done

When you count everything up, Lyndon and Lady Bird Johnson accomplished amazing things, whatever their reasons – a genuine love of country, or a need to build their own self-esteem. Does it matter? Lyndon’s contributions to the world are extraordinary, one can believe his own experiences with poverty and discrimination led him to take a strong stance against them. And Lady Bird’s example of the importance of a First Lady’s role began to break the ice; indeed her accomplishments inspire hope for the roles of all women today. She lived 34 years after Lyndon’s death, spearheading public service projects around the country and enjoying time with her daughters and grandchildren. She died at the age of 94 on July 11, 2007; eight presidents were represented at her funeral there at the ranch.

I find it interesting that Lady Bird and Jackie became friends; look at what they shared – both had step-parents and unusual family alliances, miscarriages and unfaithful husbands; yet they struggled for family solidity as their children – Caroline and John, Lynda and Lucy – were exposed to the unrelenting beam of the White House spotlight. Both women were intelligent and educated and focused on moving forward. When they were born, remember, women did not yet have the right to vote. Things continue to change.

I find it interesting that Lady Bird and Jackie became friends; look at what they shared – both had step-parents and unusual family alliances, miscarriages and unfaithful husbands; yet they struggled for family solidity as their children – Caroline and John, Lynda and Lucy – were exposed to the unrelenting beam of the White House spotlight. Both women were intelligent and educated and focused on moving forward. When they were born, remember, women did not yet have the right to vote. Things continue to change.

Go visit the LBJ ranch; you can see the homeplace, and the graves; so many stories there, along the Pedernales. Plan for springtime when the Hill Country bluebonnets are in bloom, that’s when I was there. That quiet visit will suffice as my “party with the Johnsons.”

» posted on Friday, July 19th, 2024 by Linda Lou Burton

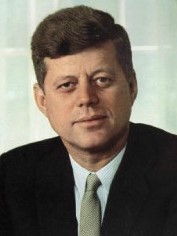

#35. Kennedy, John Fitzgerald

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas –John Fitzgerald Kennedy (1917-1963) was the 35th President of the United States, from 1961 to 1963. He was the youngest person ever elected president; his assassination, 1,036 days into his presidency, was one of the most shocking, and widely viewed events ever witnessed. Television saw to that. Ford Theater, where Abraham Lincoln was killed while watching a play in 1865, had an estimated 1,700 persons in attendance that night; certainly not all in a position to see what happened; or even hear the gunshot, as it was fired deliberately after a laugh line. James Garfield was headed for a vacation when he entered the railroad station in Washington that July morning in 1881; only a small crowd in the waiting room witnessed the gunman step forward and fire. William McKinley was attending the Pan American Exposition in Buffalo, New York when he was killed by an assassins bullet; he was in the Temple of Music surrounded by a crowd; only a few were close enough to realize what happened. After the 1901  assassination of President McKinley, Congress directed the Secret Service to hereafter protect the president of the United States.

assassination of President McKinley, Congress directed the Secret Service to hereafter protect the president of the United States.

John Kennedy was riding in a Lincoln Continental convertible in a well-publicized parade; headed for the Dallas Trade Mart to make a speech November 22, 1963; wife Jackie sat beside. Texas Governor Connally and his wife Nellie were also in the car. A Secret Service agent was driving; another sat in the front; a third, Agent Clint Hill, was following closely on the running board of the car behind. Rifle shots were fired from a sixth-story window of a building along the route as bystanders waved.

I’d just put my kids down for their afternoon nap when I first heard garbled radio accounts that “the president was shot!” Stunned reporters struggled for what to say; I turned on my TV; CBS was the first to report the news, interrupting As the World Turns. I called my husband at work to see if he’d heard anything. At 2:38 Walter Cronkite, waiting in New York for confirmation of Kennedy’s condition, was handed a sheet from the AP news ticker. He put on his glasses, took a few seconds to read the sheet, and looked into the camera with this message: President Kennedy died at 1 PM Central Time, 2 o’clock Eastern Standard Time, some thirty-eight minutes ago.

I walked into my sleeping children’s bedroom, and cried. My kids were the same age as Jackie’s and John’s. How was Jackie going to tell her children something like that?

Suspect Lee Harvey Oswald was quickly apprehended; the media swarmed the jail. Over the next four days the networks were on the air non-stop. We’d just returned from church Sunday and switched on the TV as Jack Ruby shot Oswald. It happened in the basement of the Dallas  Police Headquarters; NBC was covering, live. All networks covered the funeral on Tuesday, 50 cameras showed every detail; little John-John saluting the casket

Police Headquarters; NBC was covering, live. All networks covered the funeral on Tuesday, 50 cameras showed every detail; little John-John saluting the casket  as it passed; inside the rotunda of the Capitol little Caroline putting her hand beneath the draped flag on her father’s coffin. A country mourned with prayers, and tears, and muted disbelief.

as it passed; inside the rotunda of the Capitol little Caroline putting her hand beneath the draped flag on her father’s coffin. A country mourned with prayers, and tears, and muted disbelief.

The Other Side, and Image

And yet, there was another side. In various schoolrooms, bars, and gatherings around the country, applause greeted the news of Kennedy’s death. You see, John Kennedy didn’t become our president by a landslide. He was relatively unknown politically; he was too young. He was a Catholic. He was a rich stuck-up Bostonian with a weird accent. His daddy was a crook. Yet on election day, electoral votes, and charm, and television skewed in Kennedy’s favor.

You see, the 1960 campaign gave us the first televised debate ever. The Kennedy-Nixon Debate, up close and personal from the comfort of our own living room. Interestingly, those who listened to that first debate on the radio scored higher points for Nixon. But television favored Kennedy.

Nixon had been on the public’s radar for eight years as Eisenhower’s VP. He knew about campaigns, and was accustomed to landslide victories. But IMAGE was a new factor in the game. Kennedy met with the debate’s producer ahead of time; he checked the lighting, the temperature, the camera placement. Kennedy wore makeup, and a blue suit and shirt to cut down on glare and appear sharply focused against the background. Nixon refused the offer of makeup; his stubble showed; he looked exhausted and pale. His gray suit seemed to blend into the set; he appeared to be looking at the clock and not the camera; he kept wiping sweat off his face. Kennedy, looking young and energetic, spoke directly to the camera. Result: almost overnight, age and experience lost its importance. We had ourselves a rock star.

Nixon had been on the public’s radar for eight years as Eisenhower’s VP. He knew about campaigns, and was accustomed to landslide victories. But IMAGE was a new factor in the game. Kennedy met with the debate’s producer ahead of time; he checked the lighting, the temperature, the camera placement. Kennedy wore makeup, and a blue suit and shirt to cut down on glare and appear sharply focused against the background. Nixon refused the offer of makeup; his stubble showed; he looked exhausted and pale. His gray suit seemed to blend into the set; he appeared to be looking at the clock and not the camera; he kept wiping sweat off his face. Kennedy, looking young and energetic, spoke directly to the camera. Result: almost overnight, age and experience lost its importance. We had ourselves a rock star.

The Second Child

John Fitzgerald Kennedy was born May 29, 1917, in Brookline, Massachusetts, the second of Joseph (aka Papa Joe) and Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy’s nine children – Joseph Jr, John, Rosemary, Kathleen, Eunice, Patricia, Robert, Jean, and Edward. John’s grandfathers, both Irish immigrants, over time had served Boston as ward boss, state legislator, mayor, and even US Congressman. Papa Joe Kennedy was a businessman. A very shrewd businessman.

John Fitzgerald Kennedy was born May 29, 1917, in Brookline, Massachusetts, the second of Joseph (aka Papa Joe) and Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy’s nine children – Joseph Jr, John, Rosemary, Kathleen, Eunice, Patricia, Robert, Jean, and Edward. John’s grandfathers, both Irish immigrants, over time had served Boston as ward boss, state legislator, mayor, and even US Congressman. Papa Joe Kennedy was a businessman. A very shrewd businessman.

I’ll try to keep it short about Papa Joe; he became wealthy through investments in Hollywood, importing liquor, and real estate. He had multiple affairs with women; Gloria Swanson was one on the list. He donated big bucks to political campaigns and got juicy political appointments, such as Ambassador to the UK. He hobnobbed with royalty at Windsor Castle, and tried to meet with Hitler, who, he believed, was “on the right track.” He didn’t like Jews but he did like Joe McCarthy. He believed that Roosevelt would fall, and hoped to succeed him. That didn’t happen. So Papa Joe lined up his firstborn son to be president; but Joe Jr, a US Navy bomber pilot, was killed over the English Channel in August 1944. Papa Joe turned his attention to #2 son, John.

He Kept Going

John was intelligent, handsome, charming, and, more or less, willing to do what Dad expected of him. But John was also burdened with severe health problems. According to family records, autoimmune disease showed up in his first two years of life—he suffered from almost constant infections during infancy. A bout with scarlet fever was so dire a priest was called to administer last rites. In the first half of his life — twenty-three years — he attended school (Choate, then Harvard, where he graduated cum laude) while dealing with bronchitis, chicken pox, ear infections, colitis, celiac disease, and more; he was hospitalized for possible leukemia, and he began to experience spinal pain. But he kept going.

The last half of his life pain built on top of pain. He was rejected by the Army in 1940 due to chronic back problems, asthma, and ulcers; classified 4F. But Papa Joe had a friend who got him into the Navy; in 1942 he became skipper of PT-109; his heroism there earned him a Navy Cross; and more back problems. Three more times a priest was called to administer last rites; but he kept going. He was 30 when he was diagnosed with Addison’s disease; that’s when your body stops producing the hormones you need to balance your metabolism, blood pressure, stress response, and immune system. Wow! that’s pretty much everything you need to keep going. He was so seriously ill a priest was called; last rites administered. He was 33 when his spine got worse; and then, another attack of Addison’s while he and Robert were in Asia; he became delirious, then comatose. Last rites: #3. The year: 1950. With the aid of an unbelievable list of medically-prescribed drugs, he kept going.

The last half of his life pain built on top of pain. He was rejected by the Army in 1940 due to chronic back problems, asthma, and ulcers; classified 4F. But Papa Joe had a friend who got him into the Navy; in 1942 he became skipper of PT-109; his heroism there earned him a Navy Cross; and more back problems. Three more times a priest was called to administer last rites; but he kept going. He was 30 when he was diagnosed with Addison’s disease; that’s when your body stops producing the hormones you need to balance your metabolism, blood pressure, stress response, and immune system. Wow! that’s pretty much everything you need to keep going. He was so seriously ill a priest was called; last rites administered. He was 33 when his spine got worse; and then, another attack of Addison’s while he and Robert were in Asia; he became delirious, then comatose. Last rites: #3. The year: 1950. With the aid of an unbelievable list of medically-prescribed drugs, he kept going.

Politics and Marriage and General Hospital

In 1952 he was elected US Senator. And he met the beautiful Jacqueline Bouvier; they married the next year; he was 36, she was 24. Over the next 10 years, John was hospitalized nine times. He had spinal surgery, developed a urinary tract infection, slipped into a coma, and wasn’t expected to last the night; a priest was called for last rites for a fourth time. Jackie had a miscarriage, and then daughter Arabella was stillborn.

In 1952 he was elected US Senator. And he met the beautiful Jacqueline Bouvier; they married the next year; he was 36, she was 24. Over the next 10 years, John was hospitalized nine times. He had spinal surgery, developed a urinary tract infection, slipped into a coma, and wasn’t expected to last the night; a priest was called for last rites for a fourth time. Jackie had a miscarriage, and then daughter Arabella was stillborn.

Was the public aware, or tuned into, much of this? Not really. Great joy in January 1957 when daughter Caroline was born healthy; John started campaigning in earnest. On November 25, 1960 son John was born, just 17 days after John Fitzgerald Kennedy was elected President of the United States. Boom!

January 20, 1961 Inauguration Day for John Fitzgerald Kennedy

Priests and preachers and rabbis offered their blessings. Marian Anderson sang the Star Spangled Banner. Robert Frost wrote a special poem, and recited it, despite the sun in his eyes. Carl Sandburg and John Steinbeck and Ernest Hemingway were invited guests. Outgoing president Eisenhower was front and center there, the oldest president ever in office (at that time) handing off to the youngest. Former president Truman was there, and future presidents Johnson, Nixon and Ford were there, making it the largest “presidential fraternity” ever assembled. Plus First Ladies! Jackie Kennedy of course; Edith Wilson, Eleanor Roosevelt, Bess Truman, Mamie Eisenhower, and (as we count today, knowing the future) Lady Bird Johnson, Pat Nixon, and Betty Ford were there. Chief Justice Earl Warren administered the Presidential Oath, a Kennedy Bible was used. Then President Kennedy delivered his address, considered by many to be the best inaugural speech in American history. And the first seen by a television audience, in color.

Home viewers watched the parade too, it lasted three hours; sixteen thousand members of the US armed forces marched with displays of modern weaponry like the Minuteman missile and the supersonic B-70 bomber. Another sixteen thousand marchers were civilians – federal and state officials, high school bands, Boy Scouts, forty floats. Frank Sinatra hosted the Inaugural Ball; Broadway theaters suspended shows so actors could attend; Hollywood biggies spoke and performed as donations rolled in for the Democratic Party. Jackie stayed till 1:30 in the morning; John headed to a second party hosted by Papa Joe.

Let’s Talk About Jackie

Jacqueline Lee Bouvier (1929-1994) was born July 28, 1929 in Southampton, New York, the first child of John “Black Jack” and Janet Lee Bouvier, Wall Street stockbroker and NY socialite. Sister Caroline Lee was born four years later. The stock market crash of 1929 wasn’t the only instability in the Bouvier family; alcoholism and marital affairs caused a separation by 1936, a divorce in 1940. Janet remarried; then Jackie had Hugh Auchincloss (Standard Oil wealth) for a step-father, and three step-siblings; Janet and Hugh had two more children by 1947. And Jackie lived a pampered life in Virginia, becoming an excellent horsewoman and student, graduating top of her class. Vassar, Sorbonne, on her resume; the Kennedy years you already know. She is considered one of the top-notch First Ladies; gracious and charming in her pillbox hat, and unbelievably brave; you’ve seen the picture as she stood beside Lyndon Johnson on Air Force One that day in her pink suit stained with her husband’s blood. The American public didn’t like it when she married Greek oil magnate Aristotle Onassis in 1968 and moved her kids out of the country; he died in 1978 and she returned, working at Doubleday and Viking Press, and getting back into the public eye. She was forgiven, and remains one of the most popular women in American history. She died of cancer in 1994, age 65, and is buried in Arlington Cemetery beside John Kennedy, and their children Arabella, who was stillborn in 1956, and Patrick, who lived two days and died just 106 days before his father’s assassination.

Jacqueline Lee Bouvier (1929-1994) was born July 28, 1929 in Southampton, New York, the first child of John “Black Jack” and Janet Lee Bouvier, Wall Street stockbroker and NY socialite. Sister Caroline Lee was born four years later. The stock market crash of 1929 wasn’t the only instability in the Bouvier family; alcoholism and marital affairs caused a separation by 1936, a divorce in 1940. Janet remarried; then Jackie had Hugh Auchincloss (Standard Oil wealth) for a step-father, and three step-siblings; Janet and Hugh had two more children by 1947. And Jackie lived a pampered life in Virginia, becoming an excellent horsewoman and student, graduating top of her class. Vassar, Sorbonne, on her resume; the Kennedy years you already know. She is considered one of the top-notch First Ladies; gracious and charming in her pillbox hat, and unbelievably brave; you’ve seen the picture as she stood beside Lyndon Johnson on Air Force One that day in her pink suit stained with her husband’s blood. The American public didn’t like it when she married Greek oil magnate Aristotle Onassis in 1968 and moved her kids out of the country; he died in 1978 and she returned, working at Doubleday and Viking Press, and getting back into the public eye. She was forgiven, and remains one of the most popular women in American history. She died of cancer in 1994, age 65, and is buried in Arlington Cemetery beside John Kennedy, and their children Arabella, who was stillborn in 1956, and Patrick, who lived two days and died just 106 days before his father’s assassination.

The Aftermath

As for children Caroline and John, they grew up; John was killed in 1999 as he piloted a small aircraft; his wife and sister-in-law also died in the crash. Caroline was appointed US Ambassador to Japan under Obama’s administration; and then Ambassador to Australia by Joe Biden in 2022; choosing to live far from the USA. As for pushy Papa Joe; he lived long enough to see his son Robert assassinated by a gunshot wound to the head in 1968 as he was campaigning for the Democratic party nomination. And his son Edward drive a car off a bridge on Chappaquiddick Island in 1969, drowning his passenger, 28-year-old Mary Jo Kopechne, who was left trapped inside.

The weirdest thing in this tale of ambition and woe and television impact? Doctors tell us that if John Kennedy had not been wearing the stiff backbrace that he was confined to for the greatest part of his life, he likely would not have been killed that day. The first, and survivable, shot hit him in the back. Without a backbrace, that shot would have knocked him forward, out of range of the second shot, which, since he remained erect, hit directly in the back of his head. And the other weird thing? Records released after 2002 show that due to the overwhelming amount of drugs he was taking, and the fragility of his health, he likely would have died within a year or two anyway.

That shining spot called Camelot? John Fitzgerald Kennedy, despite all the coverups and innuendo and alleged womanizing (with all those meds, and braces?) did something good for his country; his youth and positive encouragement gave a lot of people hope. But the price tag for that rock star image was huge.

That shining spot called Camelot? John Fitzgerald Kennedy, despite all the coverups and innuendo and alleged womanizing (with all those meds, and braces?) did something good for his country; his youth and positive encouragement gave a lot of people hope. But the price tag for that rock star image was huge.

I liked him. But no party.

» posted on Thursday, July 18th, 2024 by Linda Lou Burton

#34. Eisenhower, Dwight David

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – Dwight David Eisenhower (1890-1969) was the 34th President of the United States, from 1953 to 1961. Of all the presidents who ever campaigned for president, and all the names a political party could pick to head their ticket, nobody had a better name to fit onto a campaign button: I LIKE IKE was a made-to-order winner! And then, the guy was a war hero, to boot. Five-Star General. Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces. Who better to lead a country of 160 million that was becoming, or visioning itself as, “the leader of the free world?” Supreme Commander. We know that sometimes, in order to be supreme, little things get rolled over. We know that being supreme, and being likable, are different things. Sometimes we don’t like our presidents and take aim directly (a few assassinations come to mind); sometimes we just stop voting for them, or put them down in history as NGP’s (Not Great Presidents). What did we do with Ike? And how liked was Ike?

Way Way Way Back

The “Eisenhauer” family migrated from Germany to Pennsylvania in 1741. “Eisenhauer” translates to “iron hewer;” anglicized to the spelling we know today: Eisenhower. Fast forward to October 14, 1890, and Denison, Texas. That’s when Dwight David entered the world, the third of seven sons born to David Jacob and Ida Stover Eisenhower. Ike’s family had specific times for Bible reading, and chores; discipline came from Dad if not met. Father  David was a college-educated engineer; but family fortunes went up and down over the years. Mother Ida’s childhood was a series of more downs that ups; reading the Bible was her education. When Ike was born she belonged to Jehovah’s Witnesses and their home was the local meeting hall. Dwight was named “Dwight” after evangelist Dwight L Moody; all the boys– Arthur, Edgar, Dwight, Roy, Paul, Earl, Milton – were nicknamed “Ike” as a shortened version of Eisenhower – Big Ike and Little Ike and so on; the only one still called Ike by World War II was the “Dwight Ike.” Speaking of war, keep this in mind: Mother Ida was a lifelong pacifist, believing that war was wicked. She died in September 1946; Ike was unable to attend her funeral due to war-time duties.

David was a college-educated engineer; but family fortunes went up and down over the years. Mother Ida’s childhood was a series of more downs that ups; reading the Bible was her education. When Ike was born she belonged to Jehovah’s Witnesses and their home was the local meeting hall. Dwight was named “Dwight” after evangelist Dwight L Moody; all the boys– Arthur, Edgar, Dwight, Roy, Paul, Earl, Milton – were nicknamed “Ike” as a shortened version of Eisenhower – Big Ike and Little Ike and so on; the only one still called Ike by World War II was the “Dwight Ike.” Speaking of war, keep this in mind: Mother Ida was a lifelong pacifist, believing that war was wicked. She died in September 1946; Ike was unable to attend her funeral due to war-time duties.

Becoming A Strategist

Along with his gang of brothers Ike grew up hunting, and fishing, but sports – now that was everything. As a freshman playing football, Ike injured his knee; an infection was so bad doctors told him it was life-threatening; the leg must come off. Ike refused. And got well. He graduated Abilene High School in 1909 (the family was in Kansas by then) and worked for a while to earn funds for college. Then someone suggested he apply to the Naval Academy as no tuition was required. Ike conferred with his Senator who advised applying to West Point as well. He passed the entrance exams for both but was told he was too old for the Naval Academy. He went with the second choice: West Point, 1911.

Ike made the varsity football team at West Point and was a starter halfback in 1912; yes, he played against Jim Thorpe in a famous Big Loss for Army game; in the very next game he was tackled in a knee-injuring play; no more football. Except, by doggie, he became the junior varsity coach. His graduation class of 1915 became known as “the class the stars fell on;” 59 members eventually became officers in the US Army; one of them was Dwight David Eisenhower. Ike’s academic record was average; but, in addition to learning military strategy and football strategy at West Point, he learned to play bridge. He was addicted to bridge throughout his military career. While stationed in the Philippines, he played with President Manuel Quezon and gained the reputation Bridge Wizard of Manila. He played in Europe during the stressful days before the D-Day landings. His favorite partner? General Alfred Gruenther, considered the best bridge player in the Army; Ike appointed him as second-in-command at NATO (reputedly) because of his bridge skill. Well then.

Ike made the varsity football team at West Point and was a starter halfback in 1912; yes, he played against Jim Thorpe in a famous Big Loss for Army game; in the very next game he was tackled in a knee-injuring play; no more football. Except, by doggie, he became the junior varsity coach. His graduation class of 1915 became known as “the class the stars fell on;” 59 members eventually became officers in the US Army; one of them was Dwight David Eisenhower. Ike’s academic record was average; but, in addition to learning military strategy and football strategy at West Point, he learned to play bridge. He was addicted to bridge throughout his military career. While stationed in the Philippines, he played with President Manuel Quezon and gained the reputation Bridge Wizard of Manila. He played in Europe during the stressful days before the D-Day landings. His favorite partner? General Alfred Gruenther, considered the best bridge player in the Army; Ike appointed him as second-in-command at NATO (reputedly) because of his bridge skill. Well then.

Career Army Means Moving Around

Ike’s very first military assignment was Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas. During WWI he requested to be sent to Europe but wound up training tank crews. Between wars he held staff positions in the US and the Philippines. By WWII he had attained the rank of Brigadier General; then more promotions. He oversaw the Allied invasions of North Africa and Sicily; he supervised the invasions of France and Germany. He was military governor of the American-occupied zone of Germany in 1945, Army Chief of Staff 1945-1948, and first supreme commander of NATO 1951-1952. (For a blip in there he was president of Columbia University.)

And on a personal level? Way back there in San Antonio, Ike met Mamie Doud; her parents were visiting a friend at Fort Sam Houston. He proposed on Valentine’s Day 1916, they got married July 1 (he was 26, she was 20); Ike was granted 10 days leave for a honeymoon. Mary Geneva “Mamie” Doud was born in Boone, Iowa November 14, 1896, the second of the four girls of John Sheldon and Elivera Carlson Doud. Daddy was rich, and Mama was Swedish, which meant Swedish was often spoken at home, and there were plenty of servants to do everything, so Mamie never learned to “keep house.” That didn’t make for a good start as the wife living on the low pay of a military man. But she was accustomed to one thing – not staying put. Her family traveled a lot, and had a number of homes, she grew up in Iowa, Colorado, Texas. As an Army wife she lived in 33 different homes in 37 years as Ike was stationed at different posts.

And on a personal level? Way back there in San Antonio, Ike met Mamie Doud; her parents were visiting a friend at Fort Sam Houston. He proposed on Valentine’s Day 1916, they got married July 1 (he was 26, she was 20); Ike was granted 10 days leave for a honeymoon. Mary Geneva “Mamie” Doud was born in Boone, Iowa November 14, 1896, the second of the four girls of John Sheldon and Elivera Carlson Doud. Daddy was rich, and Mama was Swedish, which meant Swedish was often spoken at home, and there were plenty of servants to do everything, so Mamie never learned to “keep house.” That didn’t make for a good start as the wife living on the low pay of a military man. But she was accustomed to one thing – not staying put. Her family traveled a lot, and had a number of homes, she grew up in Iowa, Colorado, Texas. As an Army wife she lived in 33 different homes in 37 years as Ike was stationed at different posts.

Ike and Mamie had two sons; Doud Dwight in 1917; who died of scarlet fever at the age of three; the second son, John Sheldon Doud Eisenhower was born in 1922. Ike was stationed in Panama in 1922; Mamie traveled to Denver for John’s birth; when she returned to Panama she brought a nurse to help care for John. Mamie doted on John; he helped ease some of her depression brought about by her firstborn’s death, and her long separations from Ike. In 1928 Ike was stationed in Paris; in 1929, he was appointed as aide to General Douglas MacArthur. 1935: the Philippines. 1939: Back in the US as WWII began.

It’s Been Good To Know You

During World War II, while promotion and fame came to Ike, Mamie lived in Washington, DC. During the three years Ike was stationed in Europe, she saw him only once. And what about son John; where was he during all of this? John graduated high school in Baguio, Philippines when the family lived there. And decided to follow in Dad’s footsteps – he entered West Point on the eve of the US entry into WWII. His graduation date? Incredibly, it was June 6, 1944, D-Day, the day the Allied forces invaded Normandy. Ike missed John’s graduation. Mamie’s health had never been good – she had rheumatic fever as a child; combine that with loneliness and worry; was her son okay? Her husband safe? And those Kay Summersby rumors? Officially Kay was Ike’s “chauffeur” in London, was there more?

It was 1948 before Ike and Mamie bought the first, and only, home they ever owned. Ike had accepted appointment as President of Columbia University, and the home was a farm in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. (It’s now the Eisenhower National Historic Site.) Well oops, Ike was made commander of NATO so, back to Europe, hang up that University presidency; hold up on that farm. One good thing for Mamie then – she got to live in Paris, receive royals regularly, and, was even awarded the Cross of Merit for her role in Ike’s military success. Son John, meanwhile, got married, had kids, earned an MA at Columbia in English, and began teaching English at West Point. He, and Dad, and Mom, and War, would cross paths again.

It was 1948 before Ike and Mamie bought the first, and only, home they ever owned. Ike had accepted appointment as President of Columbia University, and the home was a farm in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. (It’s now the Eisenhower National Historic Site.) Well oops, Ike was made commander of NATO so, back to Europe, hang up that University presidency; hold up on that farm. One good thing for Mamie then – she got to live in Paris, receive royals regularly, and, was even awarded the Cross of Merit for her role in Ike’s military success. Son John, meanwhile, got married, had kids, earned an MA at Columbia in English, and began teaching English at West Point. He, and Dad, and Mom, and War, would cross paths again.

The Next Republican President

Harry S Truman and Dwight David Eisenhower had different opinions about war, and policy, and, well, most things. But they had to work together during those war years. Ike didn’t approve of Harry’s decision to drop the bomb, no sir. He didn’t approve of Franklin’s “New Deal” or Harry’s “Fair Deal.” By 1952, the list of things Ike didn’t like was long, and the after-war upheaval was still stirring up everybody’s guts, so, perfect timing for a War Hero with a different plan. “I Like Ike” buttons sprouted on thousands of lapels, and by January 20, 1953, Ike and Mamie were riding in the presidential limousine on the way to the White House to pick up outgoing Harry and Bess, who invited them in for a cup of coffee before heading to the swearing-in at the capitol. Ike and Mamie wouldn’t get out of the car.

The snit began way back, all those differences of opinion. And then, right after the election but still a few months before the official change of hands, workers showed up at the White House without notice to start re-arranging the White House for the Eisenhowers. They weren’t allowed in. And then, Harry offered to set up a meeting with Ike to begin sharing critical information an incoming president would need to know (remember, he got nothing when he took over presidential duties). Ike declined, meeting with other sources for information. Mamie and Bess fared better, there is a famous photo of the two “Ladies” December 1, 1952, when Mamie accepted Bess’ offer of a tour of the White House. And so it goes.

The snit began way back, all those differences of opinion. And then, right after the election but still a few months before the official change of hands, workers showed up at the White House without notice to start re-arranging the White House for the Eisenhowers. They weren’t allowed in. And then, Harry offered to set up a meeting with Ike to begin sharing critical information an incoming president would need to know (remember, he got nothing when he took over presidential duties). Ike declined, meeting with other sources for information. Mamie and Bess fared better, there is a famous photo of the two “Ladies” December 1, 1952, when Mamie accepted Bess’ offer of a tour of the White House. And so it goes.

Who is Happy?

This is complicated. John first. Back when Ike was Supreme Allied Commander, John wasn’t allowed combat duty as it might be a distraction for his Dad. In 1952, while Ike was running for president, John was fighting in a combat unit in Korea. The heart-to-heart father-son talk

This is complicated. John first. Back when Ike was Supreme Allied Commander, John wasn’t allowed combat duty as it might be a distraction for his Dad. In 1952, while Ike was running for president, John was fighting in a combat unit in Korea. The heart-to-heart father-son talk  went like this: if I am elected president, you must never be captured alive. John accepted the fact that he would have to take his own life rather than become an instrument of blackmail; John’s children at the time – David, Ann, and Susan – were 4, 3, and 1. Ouch. John did get to work in the White House later; he was Dad’s Assistant Staff Secretary and on the Army’s General Staff.

went like this: if I am elected president, you must never be captured alive. John accepted the fact that he would have to take his own life rather than become an instrument of blackmail; John’s children at the time – David, Ann, and Susan – were 4, 3, and 1. Ouch. John did get to work in the White House later; he was Dad’s Assistant Staff Secretary and on the Army’s General Staff.

Mamie next. For eight straight years Mamie stayed put! She had a White House staff at her disposal; she looked fashionably pretty in pink; and everybody liked her bangs. She was the first First Lady to present a national public image, often entertaining heads of state, the count was over 70 official foreign visitors. She shook hands with thousands of people and readily accommodated photographers, though she maintained her distance from the press. Once John came home from Korea, she had her family near – four grandkids by 1955. John and his wife Barbara even bought property near the Gettysburg farm so they could be close.

Mamie next. For eight straight years Mamie stayed put! She had a White House staff at her disposal; she looked fashionably pretty in pink; and everybody liked her bangs. She was the first First Lady to present a national public image, often entertaining heads of state, the count was over 70 official foreign visitors. She shook hands with thousands of people and readily accommodated photographers, though she maintained her distance from the press. Once John came home from Korea, she had her family near – four grandkids by 1955. John and his wife Barbara even bought property near the Gettysburg farm so they could be close.

John liked Ike, Mamie liked Ike, and the American public continued to be wowed by Ike. He won 531 electoral votes in 1952 and 1956. He won 55% of the popular vote in 1952 and 57.5% in 1956. Could he have won a third term? Speculation is yes; but Ike was the first president to fall under the restrictions of the Two Terms Only 22nd Amendment, passed in 1951.

John liked Ike, Mamie liked Ike, and the American public continued to be wowed by Ike. He won 531 electoral votes in 1952 and 1956. He won 55% of the popular vote in 1952 and 57.5% in 1956. Could he have won a third term? Speculation is yes; but Ike was the first president to fall under the restrictions of the Two Terms Only 22nd Amendment, passed in 1951.

Winding Down

Few people were aware of Ike’s major problem: his health. In his entire military career, he never spent a day in combat, but his health brought him to the edge numerous times. Besides that screwed up knee, he had five heart attacks, one stroke, surgery due to Chrohn’s disease, malaria, tuberculosis, high blood pressure, spinal malformation, shingles, neuritis, and bronchitis. Medical records were guarded – neither a Supreme Commander nor a US President dares show any sign of weakness. He died of heart failure March 28, 1969 at the age of 78 in Walter Reed Hospital.

Mamie lived another 10 years after Ike’s death, staying on at the Gettysburg farm. She and Ike had eight years together there after leaving the White House. She died of a stroke at Walter Reed Hospital November 1, 1979 at the age of 83; she and Ike are buried side by side at the Eisenhower National Museum & Library in Abilene, Kansas.

I went to high school, got married, and had kids during Ike’s presidency; the thing I most remember was his role in 1957 when he sent Army troops to enforce federal court orders integrating Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas – I drive by the Memorial to the Little Rock Nine whenever I go downtown today. Both my brothers were in high school when Sputnik was launched; their entire careers were molded by Ike’s creation of NASA and the establishment of a stronger, science-based education via the National Defense Education Act.

I went to high school, got married, and had kids during Ike’s presidency; the thing I most remember was his role in 1957 when he sent Army troops to enforce federal court orders integrating Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas – I drive by the Memorial to the Little Rock Nine whenever I go downtown today. Both my brothers were in high school when Sputnik was launched; their entire careers were molded by Ike’s creation of NASA and the establishment of a stronger, science-based education via the National Defense Education Act.

Would I invite Ike and Mamie to my party? I don’t think so. I wore the Ike button back then. Ike and Mamie were the residents during my first tourist-visit to the White House in 1953. But it would be stressful to talk about. Too much heartache behind the glory.

» posted on Wednesday, July 17th, 2024 by Linda Lou Burton

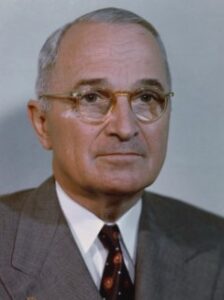

#33. Truman, Harry S

Linda Lou Burton posting from Little Rock, Arkansas – Harry S Truman (1884-1972) was the 33rd President of the United States, from 1945 to 1953. His inauguration was the seventh emergency presidential swearing in. Harry, as Vice-President , had just adjourned a session of the Senate and was headed for a drink with Sam Rayburn, then Speaker of the House, when he got a call to “Come to the White House.” He was met there by First Lady Eleanor, who informed him that “President Roosevelt is dead.” Harry asked Eleanor “Is there anything I can do for you?” And Eleanor wisely replied “Is there anything we can do for you? You are the one in trouble now.”

At 7:09 PM on Thursday, April 12, 1945, in the Cabinet Room at the White House, Chief Justice Harlan Stone administered the oath of office, beginning “Do you, Harry Shipp Truman…” to which Harry replied “I Harry S Truman…” before the oath continued. The ceremony lasted about a minute, after which Harry kissed the Bible. First Lady Eleanor was there, of course; and new First Lady Bess and daughter Margaret. Sam Rayburn, and members of the cabinet were there. This was the second inauguration in 1945; Franklin had been sworn in for his fourth term January 20; Harry was Vice President for a total of 82 days.

How To?

Those 82 days had not been training days for “how to be President” either; even though the United States was immersed in war, and Franklin’s health was failing, he didn’t take Harry into his confidence; in fact they only met alone two times. Harry was told nothing about the Manhattan Project, aka, the atomic bomb being built in secrecy. As well as a few other things a President might need to know. So Harry had to face his new job straight on, and he began right there with the oath. You see, his name was NOT Harry Shipp Truman, it really was “Harry S.” His grandfathers were Shipp Truman and Solomon Young, so Mom and Dad decided on “just S” to honor both. Harry gained another name over his years in the public arena, and that was “Give’em Hell Harry,” but I’m getting ahead of the story.

Harry S was the oldest of John Anderson and Martha Young Truman’s three children; he was born in Lamar, Missouri May 8, 1884. John was a farmer and livestock dealer. The next two children, John Vivian and Mary Jane, were born as the family moved several times in Missouri; Harrisonville, Belton, Grandview, and then Independence, where Harry attended Presbyterian Church School. At the age of seven, he began piano lessons, getting up at 5 AM to practice; something he continued for the next eight years, becoming a skilled piano player. Harry served as a Shabbos goy for his Jewish neighbors in Independence, doing tasks for them on Shabbat that their religion prevented them from doing on that day. In 1900, at the age of 16, he worked as a page at the Democratic National Convention in Kansas; his father had friends in the Democratic Party who helped Harry get that opportunity. Harry graduated high school in Independence in 1901; then took classes at business school learning bookkeeping and typing; he worked in the mailroom of the Kansas City Star for a while.

Harry S was the oldest of John Anderson and Martha Young Truman’s three children; he was born in Lamar, Missouri May 8, 1884. John was a farmer and livestock dealer. The next two children, John Vivian and Mary Jane, were born as the family moved several times in Missouri; Harrisonville, Belton, Grandview, and then Independence, where Harry attended Presbyterian Church School. At the age of seven, he began piano lessons, getting up at 5 AM to practice; something he continued for the next eight years, becoming a skilled piano player. Harry served as a Shabbos goy for his Jewish neighbors in Independence, doing tasks for them on Shabbat that their religion prevented them from doing on that day. In 1900, at the age of 16, he worked as a page at the Democratic National Convention in Kansas; his father had friends in the Democratic Party who helped Harry get that opportunity. Harry graduated high school in Independence in 1901; then took classes at business school learning bookkeeping and typing; he worked in the mailroom of the Kansas City Star for a while.

His next job gave him training in, shall we say, “vocabulary” which served him over the years in rather interesting ways. He got a job as timekeeper for construction crews on the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway, and slept in workmen’s camps along the rail lines. That’s where Harry learned to cuss. (Remember that.) Harry considered going to West Point, but was refused due to poor eyesight. So he enlisted in the Missouri National Guard in 1905 (age 21) and served until 1911, attaining the rank of corporal. How did he get in? He failed the first eye test, deemed “legally blind.” So he took the test again. This time he had memorized the eye chart.

Fast Forward to World War I

When the United States entered World War I on April 6, 1917, Harry, now 33, rejoined the Guard. He’d had farming and clerical jobs over the years, not particularly challenging; but he really hit the mark with the military. That’s where he became a leader. He successfully recruited new soldiers for his unit, Battery D, and was elected as their first lieutenant. By mid-1918, about one million soldiers of the American Expeditionary Forces were in France, and Harry, now a captain, became commander of the newly arrived Battery D, 129th Field Artillery, 35th Division. Remember what I said about Harry’s vocabulary? One bit of Army  lore about Battery D in France is called The Battle of Who Run, it goes like this: During a surprise nighttime attack by the Germans in the Vosges Mountains, the men started to flee. Harry ordered them back, using those “colorful words” from his railroad days. The men were so surprised to hear such language from him they immediately obeyed. Battery D provided support for George Patton’s tank brigade, and fired some of the last shots of the war on November 11, 1918. Harry’s unit did not lose any men under his command; his leadership was honored; on their return to the States, his men presented him with a loving cup.

lore about Battery D in France is called The Battle of Who Run, it goes like this: During a surprise nighttime attack by the Germans in the Vosges Mountains, the men started to flee. Harry ordered them back, using those “colorful words” from his railroad days. The men were so surprised to hear such language from him they immediately obeyed. Battery D provided support for George Patton’s tank brigade, and fired some of the last shots of the war on November 11, 1918. Harry’s unit did not lose any men under his command; his leadership was honored; on their return to the States, his men presented him with a loving cup.

Loving Bess. And Margaret

Elizabeth Virginia Wallace (Bess) was born February 13, 1885, in Independence, Missouri, to Margaret Elizabeth and David Willock Wallace. Bess (Bessie as a child) had three younger brothers and was a bit of a tomboy; she pursued golf, tennis, riding, basketball, ice skating; she danced at town balls and went on hayrides. And then. Her father committed suicide. She was 18 when it happened; the event was a major scandal; the family hid in Colorado for a year. Bess’s mother became a recluse, Bess cared for her the rest of her life. Bess also took the responsibility of raising her brothers; they lived in their grandparent’s house. She did go to a finishing school; and she did become “fashionable” (she loved hats, in particular). But she  determined to keep her father’s actions a secret and never spoke of him again. Put this background onto the role of “First Lady” that would be hers in 1945, maybe it explains her absolute refusal of publicity.

determined to keep her father’s actions a secret and never spoke of him again. Put this background onto the role of “First Lady” that would be hers in 1945, maybe it explains her absolute refusal of publicity.