» posted on Monday, June 3rd, 2013 by Linda Lou Burton

Brown v Board

Linda Burton posting from Topeka, Kansas – “We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place.” Such was the opinion written by Chief Justice Earl Warren in the 1954 Supreme Court Decision Brown v Board of Education. In a former schoolhouse on a side street in downtown Topeka, you can walk through a history of events that led up to that landmark decision, and what has happened since. The building, now a National Historic Site, once served as Monroe Elementary, and it still has a schoolhouse feel; in the hallway you pass drinking fountains set low enough for a kindergartner to reach;

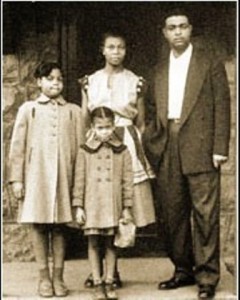

Linda Burton posting from Topeka, Kansas – “We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place.” Such was the opinion written by Chief Justice Earl Warren in the 1954 Supreme Court Decision Brown v Board of Education. In a former schoolhouse on a side street in downtown Topeka, you can walk through a history of events that led up to that landmark decision, and what has happened since. The building, now a National Historic Site, once served as Monroe Elementary, and it still has a schoolhouse feel; in the hallway you pass drinking fountains set low enough for a kindergartner to reach;  there’s the smell of chalk, and echoes in the hall. Monroe Elementary was one of four all-black elementary schools in Topeka when it was selected by NAACP strategists in 1950 as part of a larger plan to bring the “separate but equal” doctrine into the courts. With NAACP guidance thirteen sets of parents agreed to attempt to enroll their children in white schools, not expecting to be admitted, and then file complaints. Linda Brown (b 1942) was a third grader at Monroe at the time her

there’s the smell of chalk, and echoes in the hall. Monroe Elementary was one of four all-black elementary schools in Topeka when it was selected by NAACP strategists in 1950 as part of a larger plan to bring the “separate but equal” doctrine into the courts. With NAACP guidance thirteen sets of parents agreed to attempt to enroll their children in white schools, not expecting to be admitted, and then file complaints. Linda Brown (b 1942) was a third grader at Monroe at the time her  parents Leola and Oliver Brown decided to participate; alphabetically “Brown” was the first name on the lawsuit; forever after Brown v Board of Education is the name associated with the end of public school segregation in the United States. The full story, however, is multi-layered and complex; the exhibits in the Brown v Board of Education National Historic Site take you through the key points, even going further back in time than the 1896 Supreme Court decision when Plessy v Ferguson put the “separate but equal” doctrine legally into place. Race and the American Creed is the place to start; it’s a movie in the auditorium.

parents Leola and Oliver Brown decided to participate; alphabetically “Brown” was the first name on the lawsuit; forever after Brown v Board of Education is the name associated with the end of public school segregation in the United States. The full story, however, is multi-layered and complex; the exhibits in the Brown v Board of Education National Historic Site take you through the key points, even going further back in time than the 1896 Supreme Court decision when Plessy v Ferguson put the “separate but equal” doctrine legally into place. Race and the American Creed is the place to start; it’s a movie in the auditorium.

The Education and Justice exhibit examines the barriers African Americans faced in trying to receive a formal education from the early 19th century to the 1954 Supreme Court decision. A map outlines “Segregation in 1950;” a study of the map helps to understand the strategy that was part of the desegregation effort. A total of five different cases were consolidated into what was officially listed as Oliver L Brown et al v The Board of Education of Topeka et al – from Delaware, South Carolina, Virginia, and Washington DC, in addition to the Kansas case. Deliberately drawn from different areas of the country, because focusing on the south would have introduced other political complications, Topeka was chosen as the lead case although segregation was not required in Kansas, and the Topeka schools were essentially equal to the white schools there. The idea was to focus on “segregation” itself, and not equality.

The Education and Justice exhibit examines the barriers African Americans faced in trying to receive a formal education from the early 19th century to the 1954 Supreme Court decision. A map outlines “Segregation in 1950;” a study of the map helps to understand the strategy that was part of the desegregation effort. A total of five different cases were consolidated into what was officially listed as Oliver L Brown et al v The Board of Education of Topeka et al – from Delaware, South Carolina, Virginia, and Washington DC, in addition to the Kansas case. Deliberately drawn from different areas of the country, because focusing on the south would have introduced other political complications, Topeka was chosen as the lead case although segregation was not required in Kansas, and the Topeka schools were essentially equal to the white schools there. The idea was to focus on “segregation” itself, and not equality.

States Requiring Segregated Schools in 1950

- Alabama

- Arkansas

- Delaware

- Florida

- Georgia

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maryland

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- North Carolina

- Oklahoma

- South Carolina

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Virginia

- West Virginia

States Permitting Segregated Schools in 1950

- Arizona

- Kansas

- New Mexico

- Wyoming

States Prohibiting Segregated Schools in 1950

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- New Jersey

- New York

- Ohio

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- Washington

- Wisconsin

States With No Specific Legislation on Segregation in 1950

- California

- Maine

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- North Dakota

- Oregon

- South Dakota

- Utah

- Vermont

“Does segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race, even though the  physical facilities and other ‘tangible’ factors may be equal, deprive the children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities? We believe that it does.” The May 17, 1954 Supreme Court decision unanimously declared that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal” and, as such, violated the 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution, which guarantees all citizens “equal protection of the laws.” The holding that “separate” by itself was unconstitutional was what made Brown v Board of Education the landmark case in school desegregation.

physical facilities and other ‘tangible’ factors may be equal, deprive the children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities? We believe that it does.” The May 17, 1954 Supreme Court decision unanimously declared that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal” and, as such, violated the 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution, which guarantees all citizens “equal protection of the laws.” The holding that “separate” by itself was unconstitutional was what made Brown v Board of Education the landmark case in school desegregation.

The next exhibit in the Site shows the Legacy; the impacts both domestically and  internationally. Prince Edward County, Virginia closed its schools from 1959 to 1964 rather than comply with the Supreme Court’s order to integrate schools “with all deliberate speed.” In other places desegregation was met with angry, and often violent, resistance; openly segregated public facilities persisted into the 1960’s. Linda Brown was in junior high by the time of the Supreme Court ruling; she went on to Washburn and Kansas State universities, married and had children and grandchildren of her own. She was on the speaker circuit with regard to civil rights issues and worked as an educational consultant. Her father, Oliver Brown, died in 1961.

internationally. Prince Edward County, Virginia closed its schools from 1959 to 1964 rather than comply with the Supreme Court’s order to integrate schools “with all deliberate speed.” In other places desegregation was met with angry, and often violent, resistance; openly segregated public facilities persisted into the 1960’s. Linda Brown was in junior high by the time of the Supreme Court ruling; she went on to Washburn and Kansas State universities, married and had children and grandchildren of her own. She was on the speaker circuit with regard to civil rights issues and worked as an educational consultant. Her father, Oliver Brown, died in 1961.

Monroe Elementary closed in 1975 due to declining enrollment and the building changed hands several times before the Brown Foundation began a crusade to save it. The Trust for Public Land purchased the property in 1991; on October 26, 1992 President George Bush signed legislation establishing it as a National Historic Site. Title was transferred to the National Park Service in December 1993; the Brown Foundation continues to help minority students pursue careers in education.

About the Brown Foundation www.brownvboard.org

About the Brown v Board National Historic Site @ 1515 SE Monroe Street, Topeka, 785-354-3273, www.nps.gov/brvb