» posted on Monday, October 21st, 2013 by Linda Lou Burton

Messing Things Up

Linda Burton posting from Providence, Rhode Island —Changing the status quo can be messy. And Roger Williams (1603-1683) messed things up wherever he went. Roger didn’t mean to create problems, he meant to simplify. At least, that’s the way it’s interpreted now. Now he’s deemed a hero, a fighter for freedom, and, no small accomplishment – the founder of Rhode Island. The Roger Williams National Memorial, operated by the National Park Service, occupies 4.5 acres in downtown Providence, near the corner of Smith and North Main. The Rhode Island State House is just across the easy-flowing Moshassuck River, an impressive sight through the October-gold of the park’s trees. A pot of yellow mums sat by the building’s door; inside, a solemn wooden statue in patriotic blues and golds held a book. I started with the overview movie of Roger Williams’ life; I browsed

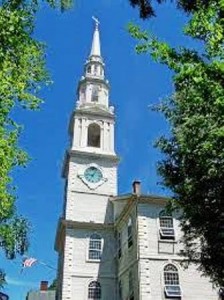

Linda Burton posting from Providence, Rhode Island —Changing the status quo can be messy. And Roger Williams (1603-1683) messed things up wherever he went. Roger didn’t mean to create problems, he meant to simplify. At least, that’s the way it’s interpreted now. Now he’s deemed a hero, a fighter for freedom, and, no small accomplishment – the founder of Rhode Island. The Roger Williams National Memorial, operated by the National Park Service, occupies 4.5 acres in downtown Providence, near the corner of Smith and North Main. The Rhode Island State House is just across the easy-flowing Moshassuck River, an impressive sight through the October-gold of the park’s trees. A pot of yellow mums sat by the building’s door; inside, a solemn wooden statue in patriotic blues and golds held a book. I started with the overview movie of Roger Williams’ life; I browsed  the exhibits, and the gift shop. The Park Ranger gave me a walking map, marking spots in Providence that were important to the Roger Williams story. Enough time inside; I headed for the First Baptist Church in America, a few blocks down Main Street. I passed the Hahn Memorial along the way, and the spring that was discovered by Roger Williams in the 1600s. Roger built his house nearby (although it no longer exists); that fresh-water spring sustained not only Roger and his family, but the settlers that followed. Judge Jacob Hahn donated the land for the park, and the memorial,

the exhibits, and the gift shop. The Park Ranger gave me a walking map, marking spots in Providence that were important to the Roger Williams story. Enough time inside; I headed for the First Baptist Church in America, a few blocks down Main Street. I passed the Hahn Memorial along the way, and the spring that was discovered by Roger Williams in the 1600s. Roger built his house nearby (although it no longer exists); that fresh-water spring sustained not only Roger and his family, but the settlers that followed. Judge Jacob Hahn donated the land for the park, and the memorial,  to the city of Providence in 1931; it was given in honor of his father Isaac Hahn, the first person of Jewish faith to be elected to public office from Providence. These items offer hints of what Roger Williams stood for, and that was “freedom of conscience.” Should I start at the beginning, or the end?

to the city of Providence in 1931; it was given in honor of his father Isaac Hahn, the first person of Jewish faith to be elected to public office from Providence. These items offer hints of what Roger Williams stood for, and that was “freedom of conscience.” Should I start at the beginning, or the end?

The First Amendment to the US Constitution states: Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.

But things didn’t really start out that way as people came to settle a new land. Do you know the temper of England when Roger was born in London in 1603? Strict religious conformity to the church was demanded; Catholics and radical Puritans were publicly humiliated,  tortured, and sometimes put to death. You’ve heard the story (a thousand times) of the Pilgrims and their move to Massachusetts “seeking religious freedom;” it was 1629 when Puritans founded the Massachusetts Bay Colony and sailed away, settling in Boston and several other spots.

tortured, and sometimes put to death. You’ve heard the story (a thousand times) of the Pilgrims and their move to Massachusetts “seeking religious freedom;” it was 1629 when Puritans founded the Massachusetts Bay Colony and sailed away, settling in Boston and several other spots.

Roger’s father was a merchant involved in world trade; Roger was educated at Cambridge and fluent in several languages. He had trained as an Anglican clergyman, but he began to sympathize with the Puritans; in 1631 he and wife Mary left England too. When he arrived in Boston, ostensibly to head a church, he determined that the “new church” had not really separated from the “old,” and refused to accept his new post. He accused the Puritans of “middle walking” and said they should completely separate from the Anglican Church. They refused. Roger made a stink! He was at odds with the Puritans over other issues too – he rejected “civil jurisdiction” over the first four of the Ten Commandments, and he disputed English charters that “took” land from the natives. He denounced “hireling” ministers paid from taxes, and civil oaths taken in God’s name. He took a strong stand for the “separation of  church and state.” What happened? Massachusetts Bay sentenced the troublemaker for sedition and heresy and scheduled him for deportation; before they came to apprehend him, he slipped away in the night.

church and state.” What happened? Massachusetts Bay sentenced the troublemaker for sedition and heresy and scheduled him for deportation; before they came to apprehend him, he slipped away in the night.

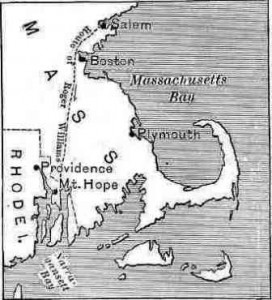

It was February 1636 when Roger stopped far to the south near Narragansett Bay. Likely he would have frozen, or starved, had it not been for the Wampanoag. They offered him shelter and took him to the winter camp of Massasoit, the leader. He resided there till springtime, when he bought some land from Massasoit and, with some followers from Salem, began a settlement. The Plymouth Colony warned he was still within their land grant and threatened extradition. Another move; this time across the Seekonk  River beyond any charter. This was Narragansett territory; Roger negotiated with the Narragansett chiefs for land; this time, the settlement stuck. Roger called the spot Providence because he felt that “God’s Providence” had brought him there. The settlement was to be a haven for those “distressed of conscience,” and soon it had attracted a collection of dissenters.

River beyond any charter. This was Narragansett territory; Roger negotiated with the Narragansett chiefs for land; this time, the settlement stuck. Roger called the spot Providence because he felt that “God’s Providence” had brought him there. The settlement was to be a haven for those “distressed of conscience,” and soon it had attracted a collection of dissenters.

From the beginning, the settlement was governed by majority vote, but only in “civil things.” Roger was deeply religious, but he believed that an individual’s relationship with God (or lack thereof) was a personal matter, not to be dictated by the government. He saw the first four of the Ten  Commandments – covering blasphemy, false worship, idolatry, and failure to keep the Sabbath – as “matters of conscience.” The last six, forbidding lying, cheating, stealing, murdering, and in general, being really nasty to the people around you – he saw as the “rules for living” in which the government had a right to intervene.

Commandments – covering blasphemy, false worship, idolatry, and failure to keep the Sabbath – as “matters of conscience.” The last six, forbidding lying, cheating, stealing, murdering, and in general, being really nasty to the people around you – he saw as the “rules for living” in which the government had a right to intervene.

Roger did not casually accept all faiths; he had his own strong beliefs. But in the new Rhode Island settlement, all forms of worship were allowed. Baptists were barred from Massachusetts, but not Rhode Island. Quakers were allowed in Rhode Island; Jews, who were not even considered citizens in Europe, were granted citizenship in Rhode Island. Rhode Island’s first charter said that as long as a person obeyed all civil laws, they could “walk as their consciences persuade them.”

From the NPS brochure:

Williams likened Rhode Island to “many a hundred souls in one ship.” The captain should punish those who “refuse to obey the common laws and orders of the ship,” but “none of the Papists, Protestants, Jews, or Turks should be forced to come to the Ship’s Prayers or Worship; nor, secondly, compelled from their own particular Prayers or Worship, if they practice any.” This compelling image of the state’s role would set the pattern for a nation.

And that takes us back to the First Amendment to the US Constitution, where Roger’s passion for “freedom of conscience” eventually became the law of the land.

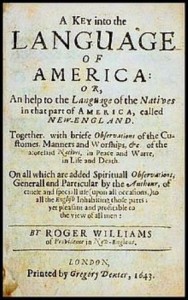

Roger’s other quest did not turn out so well; remember that he questioned the legitimacy of the English land charters, and the taking of land from the natives. He spent a lifetime working for the rights of the native Algonquian-speaking tribes. He defended their rights. He learned their languages and their customs. He preached the gospel and lived the Christian life as an example to them, but believed they, as much as any European, had the right to worship as  they wished. He condemned mass Native American conversions and wrote a religious tract Christenings make not Christians. And he was a friend. When Canonicus, leader of the Narragansett, lay dying, he asked that Roger attend his funeral and that he be buried in clothes Roger had given him. But all Roger’s efforts bore little fruit; by 1676 the native cultures were reeling from war and disease; Europeans would take virtually all of their lands.

they wished. He condemned mass Native American conversions and wrote a religious tract Christenings make not Christians. And he was a friend. When Canonicus, leader of the Narragansett, lay dying, he asked that Roger attend his funeral and that he be buried in clothes Roger had given him. But all Roger’s efforts bore little fruit; by 1676 the native cultures were reeling from war and disease; Europeans would take virtually all of their lands.

Roger established a trading post in 1637 which he later sold to finance his trips to England to secure a charter for the colony; he cofounded the first Baptist church in North America in 1638 but was a member only for a year, believing that “no earthly church could fit the first and ancient pattern of the New Testament.” He wrote a number of books. A Key into the Language of America was the first extensive lexicon of an American Indian language, it was a best-seller in England. His most famous book, The Bloody Tenent of Persecution for Cause of Conscience, published when he was in England in 1644, did not fare so well; Parliament  responded by ordering the public hangman to burn the book. By then, Williams was already on his way back home to America.

responded by ordering the public hangman to burn the book. By then, Williams was already on his way back home to America.

Roger and Mary Barnard Williams had six children, all born in America – Mary, Freeborn, Providence (born in Providence), Mercy, Daniel, and Joseph. Mary died in 1676; Roger’s health deteriorated in his later years and he died, almost destitute, in 1683. On Prospect Terrace in Providence, a large statue of Roger Williams marks where the remains of he and Mary were reinterred in 1939.

Inscribed over the Rhode Island State House portico are these words from the colony’s 1663 royal charter, sought for and obtained by Roger Williams: To hold forth a lively experiment that a most flourishing civil state may stand and best be maintained with full liberty in religious concernments.

I walked on down Main Street to the First Baptist Church in America, celebrating its 375th year, walked around inside and out, and completed the loop back to my car. In every direction I looked, church spires of varying design rose high above the city streets of Providence. Sometimes you have to mess things up, it seems, to get them going in the right direction.

I walked on down Main Street to the First Baptist Church in America, celebrating its 375th year, walked around inside and out, and completed the loop back to my car. In every direction I looked, church spires of varying design rose high above the city streets of Providence. Sometimes you have to mess things up, it seems, to get them going in the right direction.

First Baptist Church in America, 75 N Main Street, 401-454-3418, www.firstbaptistchurchinamerica.org/

Roger Williams National Memorial, 282 N Main Street, 401-521-7266, www.nps.gov/rowi

- The first Baptist church in North America was founded in Rhode Island.

- The first Jewish synagogue in North America was built in Rhode Island.

- One of the first Quaker meeting houses in North America was established in Rhode Island.